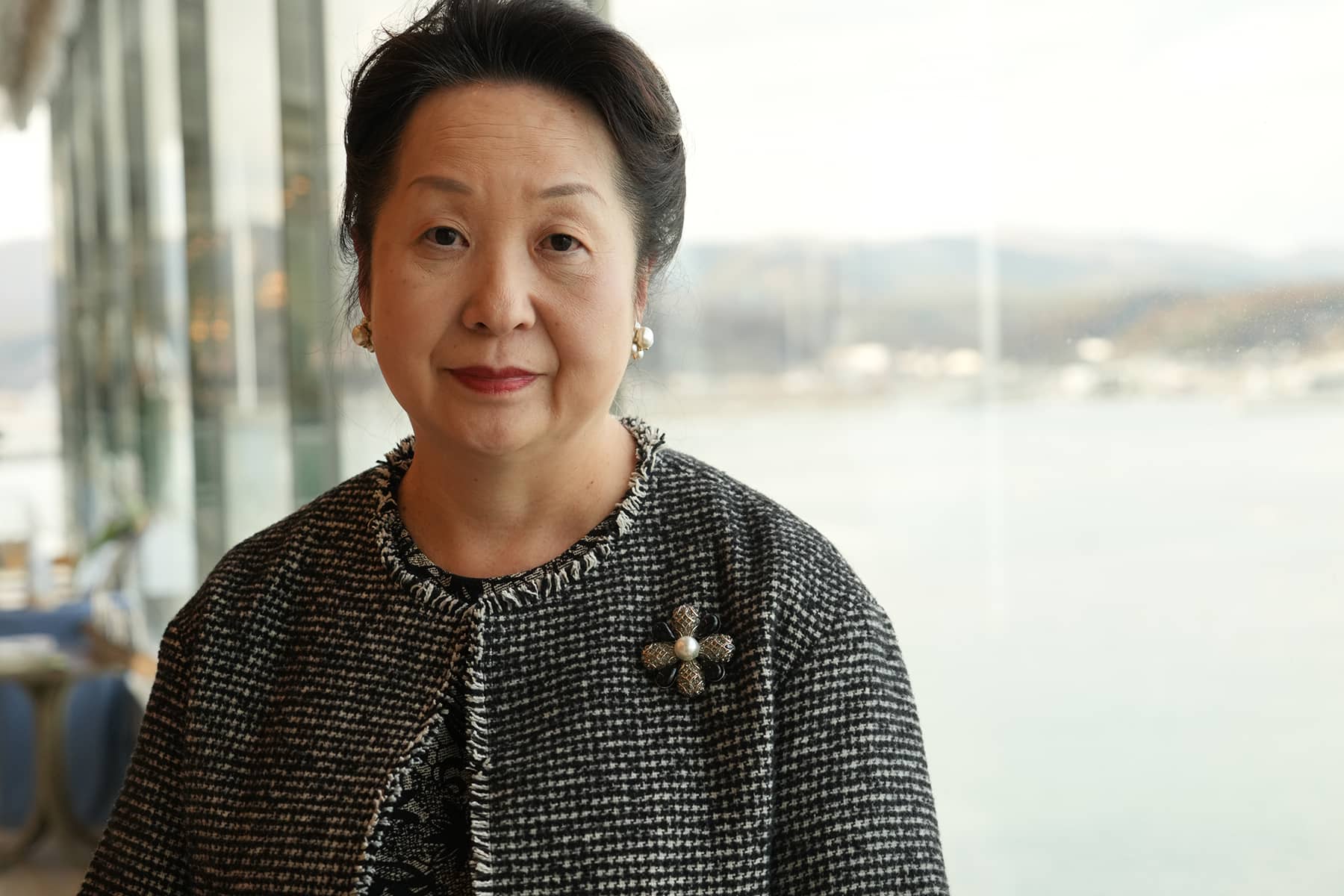

There are many voices in the aftermath of a catastrophe to speak about those tragic events and how they unfolded. In the coastal city of Minamisanriku, Abe Noriko personifies the voice of hope and resilience woven into the story of the worst natural disaster in recent memory, the Great East Japan Earthquake.

Located specifically on Shizugawa Bay by its founder Taiji Abe, the Minami Sanriku Hotel Kanyo is known for its outdoor onsen hot spring that overlooks the ocean and a place to experience the true meaning of Japanese hospitality. In the wake of the March 11, 2011 earthquake and tsunami it became renowned as a symbol of safety and recovery for many who emerged from the rubble. It also played an important role in the recovery of the Minamisanriku community.

“The building in Kesennuma with the spiral staircase, that’s my childhood home,” said Abe, General Manager of the hotel and Taiji’s eldest daughter. “Having lost everything to the tsunami caused by the Chilean earthquake in 1960, my father was very conscious about disaster prevention. He was always thinking about what preparations were necessary to help local residents and protect our community.”

With meticulous research and a determination to safeguard the area, her father discovered an area of beautiful land that was situated on solid bedrock, prompting the construction of the hotel.

“He built this place above sea level, and it was his foresight that spared us from total destruction,” said Abe. “When the tsunami hit, it reached as high as the second floor. The first two floors were left in a tragic state, but the lounge on the fifth floor didn’t even have broken glass. The merchandise in the shop didn’t fall off the shelves.”

As the reality of the disaster unfolded, the hotel became a refuge for the displaced. Abe quickly took charge, guiding residents to safety and setting up a command center to coordinate relief efforts.

“People kept arriving, pale and panicked, so we had to act fast,” she recalled.

The adjacent dormitory for female employees, equipped with a childcare facility, provided much-needed solace in those early hours for those who lost everything and were hardest affected.

In the aftermath of the disaster, Abe and her community faced unprecedented challenges. It was common for commercial buildings to have their “machine rooms” in the basement, which all the mechanical equipment like air handlers, boilers, heat exchangers, water heaters, pumps, backup generators, and elevator machinery.

Abe’s father chose a different location and all three machine rooms were protected. However, the location became isolated as electricity and water were cut off, and the roads were blocked.

“Water was unavailable for four months, so we collected rainwater and fetched water from the river to survive,” said Abe. “Electricity was out for two months, and we could only use the radio for a limited time each day because we did not know how long our batteries could last.”

Before long, the hotel had taken in 600 survivors. Which meant 600 meals had to be prepared daily without water. Abe said they dealt with the situation as best they could from one day to the next. Looking back, she said it felt surreal and could relate to the situation facing so many people in Noto after the New Year’s Day earthquake.

“The Great East Japan Earthquake taught us many invaluable lessons about disaster preparedness and community resilience,” said Abe. “That inspired us to host a storytelling symposium here. We realized that recovery isn’t just a physical state but also a mental one. It was about extending a hand to those in need, showing empathy, and taking action in the face of adversity.”

Many of the hotel staff were also affected by the disaster. It helped change their culture for the better. Sharing stories and discussing their experiences was a delicate matter within the disaster-affected areas. Yet, such conversations proved to offer healing and a sense of being understood by others. The inadvertent hurt sparked by some discussions was unavoidable, but those early conversations provided a broader perspective on shared challenges and were essential for healthy community building.

The Kataribe storytelling tours evolved from those experiences. They were originally designed for organized groups, but Abe and her staff realized the importance of reaching any individual interested in learning, regardless of the number.

“That led us to arrange for buses, to ensure transportation for those without cars, especially from Sendai,” said Abe. “It really highlighted the inconvenience of secondary transportation in rural towns. The situation also underscored the disparities between urban and rural areas, emphasizing the need for better transportation solutions in regions like ours.”

Abe was an advocate for recovery operations, and helped address the lack of response regarding vital infrastructure by local governments. She said that work demonstrated the importance of active participation in urban planning. The outcome of the efforts was varied, with some areas achieving more favorable results than others. It underscored the importance of resilience and community advocacy in facing challenges.

“Even though an area like Minamisanriku might not be as developed as the urban centers, there’s a certain charm,” said Abe. “The ability to maintain a comfortable distance from others is a characteristic of the Tōhoku region. However, some conveniences can only improve with the increase in the number of visitors. That remains a challenge here even for domestic tourism. It’s also difficult to increase visitor numbers without the memory of the disaster fading too quickly.”

Abe is behind the private preservation of a handful of relic sites. She said that it was impossible to convey the full impact of the 2011 tsunami without seeing the disaster remnants. As many of the remnants were dismantled, it she said it really drove home the point of how necessary it was for people to witness the sites firsthand in order to fully grasp the scale of the destruction.

“Ideally, these remnants should be preserved privately. But that presents significant economic challenges, especially in Miyagi Prefecture where mostly the schools have been preserved,” said Abe.

Her concern was that numerous small memorials were being created to drive “disaster tourism” and their questionable purposes could dilute attention from the larger and more culturally important sites. That was why supporting the Kataribe storytellers themselves rather than focusing solely on constructing hard memorials became her main focus, especially as COVID-19 significantly hampered their activities.

“It feels like the focus has been too much on building physical structures without considering if they were what the community really wanted or needed,” she said. “For example, having access to video presentations allows people even in distant locations to learn about our experiences. It’s been crucial that the stories of those who lived through these events are heard directly while they are still able to share.”

Understanding the significance of educational trips, Abe and her staff took the initiative early on despite facing opposition. The effort to convince skeptics, especially from regions near Fukushima with varied perspectives, was challenging but crucial in demonstrating the educational value of visiting disaster-affected areas.

The willingness of new schools to participate in Kataribe tours, driven by a belief in the importance of learning from real-life situations, has led to an increase in educational visits. Today Abe’s program assists a significant number of schools, helping shape a generation of leaders informed by the lessons of disaster preparedness and community resilience.

“This experience has been transformative, not only in terms of community rebuilding and educational engagement but also in highlighting the intrinsic value of our actions and the importance of continuity in our efforts,” said Abe. “The challenges we’ve faced, and the losses we’ve endured, have been immeasurable. But so have the connections and the sense of purpose we’ve found in the aftermath. These initiatives aren’t just about receiving support. They’re about actively facilitating community interactions to foster a sense of belonging and collective progress.”

Focusing on families with children and business owners to ensure the community’s survival required her team to rethink their strategies.

“It became evident that children who moved away for schooling seldom returned, given the rapid adaptation characteristic of youth,” added Abe. “That concern extended to business owners, whose enterprises were largely wiped out. It underscored the importance of job creation and economic revitalization in disaster-struck areas.”

Abe said that through their efforts, they have seen the importance of proactive engagement, community support, and the power of education in shaping a resilient future. The approach, grounded in real-life experiences and shared learning, has continued to drive Abe’s commitment to rebuilding and reimagining her community for the better.

3.11 Exploring Fukushima

- Journey to Japan: A photojournalist’s diary from the ruins of Tōhoku 13 years later

- Timeline of Tragedy: A look back at the long struggle since Fukushima's 2011 triple disaster

- New Year's Aftershock: Memories of Fukushima fuels concern for recovery in Noto Peninsula

- Lessons for future generations: Memorial Museum in Futaba marks 13 years since 3.11 Disaster

- In Silence and Solidarity: Japan Remembers the thousands lost to earthquake and tsunami in 2011

- Fukushima's Legacy: Condition of melted nuclear reactors still unclear 13 years after disaster

- Seafood Safety: Profits surge as Japanese consumers rally behind Fukushima's fishing industry

- Radioactive Waste: IAEA confirms water discharge from ruined nuclear plant meets safety standards

- Technical Hurdles for TEPCO: Critics question 2051 deadline for decommissioning Fukushima

- In the shadow of silence: Exploring Fukushima's abandoned lands that remain frozen in time

- Spiral Staircase of Life: Tōhoku museums preserve echoes of March 11 for future generations

- Retracing Our Steps: A review of the project that documented nuclear refugees returning home

- Noriko Abe: Continuing a family legacy of hospitality to guide Minamisanriku's recovery

- Voices of Kataribe: Storytellers share personal accounts of earthquake and tsunami in Tōhoku

- Moai of Minamisanriku: How a bond with Chile forged a learning hub for disaster preparedness

- Focus on the Future: Futaba Project aims to rebuild dreams and repopulate its community

- Junko Yagi: Pioneering a grassroots revival of local businesses in rural Onagawa

- Diving into darkness: The story of Yasuo Takamatsu's search for his missing wife

- Solace and Sake: Chūson-ji Temple and Sekinoichi Shuzo share centuries of tradition in Iwate

- Heartbeat of Miyagi: Community center offers space to engage with Sendai's unyielding spirit

- Unseen Scars: Survivors in Tōhoku reflect on more than a decade of trauma, recovery, and hope

- Running into history: The day Milwaukee Independent stumbled upon a marathon in Tokyo

- Roman Kashpur: Ukrainian war hero conquers Tokyo Marathon 2024 with prosthetic leg

- From Rails to Roads: BRT offers flexible transit solutions for disaster-struck communities

- From Snow to Sakura: Japan’s cherry blossom season feels economic impact of climate change

- Potholes on the Manga Road: Ishinomaki and Kamakura navigate the challenges of anime tourism

- The Ako Incident: Honoring the 47 Ronin’s legendary samurai loyalty at Sengakuji Temple

- "Shōgun" Reimagined: Ambitious TV series updates epic historical drama about feudal Japan

- Enchanting Hollywood: Japanese cinema celebrates Oscar wins by Hayao Miyazaki and Godzilla

- Toxic Tourists: Geisha District in Kyoto cracks down on over-zealous visitors with new rules

- Medieval Healing: "The Tale of Genji" offers insight into mysteries of Japanese medicine

- Aesthetic of Wabi-Sabi: Finding beauty and harmony in the unfinished and imperfect

- Riken Yamamoto: Japanese architect wins Pritzker Prize for community-centric designs

MI Staff (Japan)

Lее Mаtz

3.11 Exploring Fukushima: The Tōhoku region of Japan experienced one of the worst natural disasters ever recorded when a powerful earthquake was followed by a massive tsunami, and triggered an unprecedented nuclear crisis in 2011. With a personal connection to the tragedies, Milwaukee Independent returned for the first time in 13 years to attend events commemorating the March 11 anniversary. The purpose of the journalism project included interviews with survivors about their challenges over the past decade, reviews of rebuilt cities that had been washed away by the ocean, and visits to newly opened areas that had been left barren by radiation. This special editorial series offers a detailed look at a situation that will continue to have a daily global impact for generations. mkeind.com/exploringfukushima