For the city of Sendai, the bustling heart of Miyagi Prefecture, March 11, 2011 began like any other. But it would end as a day etched forever in the nation’s collective memory. Not just as a moment in history, but as a life-altering event that reshaped the very existence of people across vast regions of Japan.

It was a Friday, just before the weekend. People were winding down their workweek, schools were letting out, and the city was its usual, lively self. Then at 14:46 the ground beneath Sendai did more than just shake, it violently convulsed.

Buildings that had stood proud for decades swayed as if made of paper. The 9.0 magnitude earthquake originated off the Tōhoku coast. It unleashed a force that Sendai, for all its modernity and preparedness, had never quite imagined.

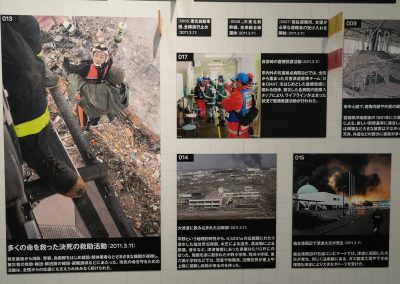

Minutes later, a more ominous threat emerged from the sea. A towering wall of water, energized by the earthquake’s force, raced towards the coast with relentless fury. It was not just a wave but a moving mountain of water, obliterating everything in its path.

Coastal neighborhoods, once vibrant and full of life, were swept away in moments. The reality was stark. Nature had reclaimed what was once its own, leaving behind a landscape of devastation.

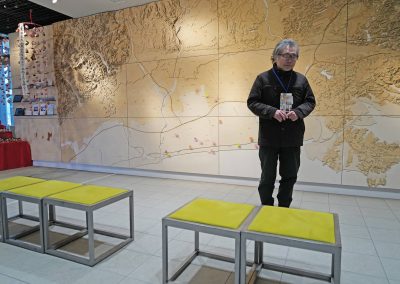

“We were having a meeting in a cultural facility on March 11 in a place called Asahigaoka, maybe on the third floor,” said Aono Yuji, director of the Sendai 3.11 Memorial Exchange Hall. “We had attendees from Iwaki and other regions of Sendai City. Many people had come from far away. Everyone ended up in a situation where they couldn’t go home.”

The tsunami eventually receded, but the scars remained. Streets were littered with the remnants of the lives that had been lost, a child’s shoe, a photo album, a battered car stuck in a tree. The death toll rose as the days passed, each name a story, each a profound loss.

Families huddled in shelters, grappling not only with the loss of their homes but the very fabric of their community.

“Two days later, I started helping at the evacuation centers,” Yuji told Milwaukee Independent. “Since we couldn’t do our jobs anymore, we helped with the city administration. Commuting was very difficult. Either you couldn’t walk somewhere, or you had to walk everywhere. It was an unbelievable situation.”

Yuji was not originally from Sendai, but lived relatively nearby in Fukuda. His family was safe, but all around him and his loved ones was either partial or total destruction. People like his brother were safe, but his house in Iwate was washed away.

The immediate aftermath revealed a grim reality: thousands died, many more injured, and countless others missing. The disaster uprooted families, leaving tens of thousands without homes, seeking refuge in temporary shelters. The community’s fabric was torn asunder, with the loss of life touching nearly every resident in some manner. The psychological impact, compounded by the physical devastation, posed significant challenges to the city’s recovery.

The environmental damage in and around Sendai was profound, with agricultural lands swamped by saltwater, green areas destroyed, and local ecosystems disrupted. Economically, the disaster struck a severe blow to the region’s industries. The halt in production, combined with the destruction of infrastructure, meant a long road to economic recovery, with repercussions felt in both local and global markets.

“So, at that time, when I talked about this with my friends, there was always someone among their friends who had suffered some unbelievable loss,” said Yuji. “So it gave me the idea to create a memorial site for Sendai.”

At the time, Sendai’s subway did not extend to the Wakabayashi ward. But plans had been in development for some time to extend the Tōzai Line to Arai near the coast. Yuji thought that if the subway was coming that far, a facility should be created at the entrance where people displaced by the disaster could connect.

“Simply put, we started as a community center and not as a museum,” said Yuji. “That’s how it all started.”

The road to recovery was, and remains, slow but steady. Sendai’s people picked up the pieces, not just of their city but of their lives. The rebuilding went beyond infrastructure. It was about restoring a sense of normalcy, of community, of home. Markets reopened, children returned to school, and bit by bit, laughter began to fill the air once again.

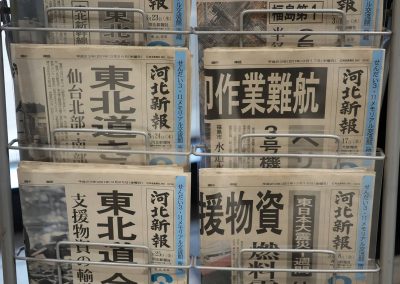

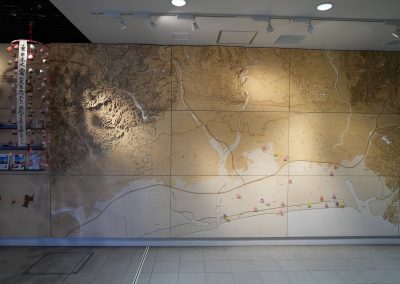

The community space on the first floor features a 3D topographic map, plus slides and related books for learning about Sendai’s eastern coastal area. The exhibition room on the second floor has a permanent exhibition that shows the damage caused by the earthquake and tsunami and the state of restoration and reconstruction in the city, plus special exhibitions that present the natural disaster through various lenses.

A range of exhibitions have been held so far, including photographs of life and landscapes in the eastern coastal area of Sendai City before the Great East Japan Earthquake, and scientific displays that answer questions about natural phenomena such as earthquakes and tsunamis. There is a rooftop garden on the third floor where visitors can take a break, which is also used as an event space.

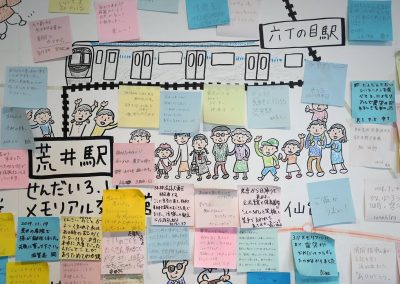

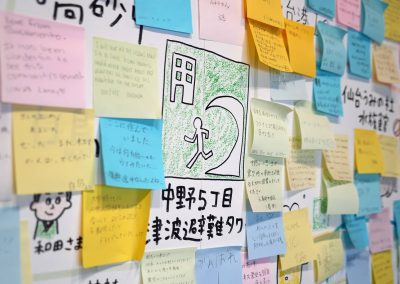

A unique exhibit is the Sendai Coast Illustration Map on the second floor. Illustrator Junko Sato, who lives in Sendai, created an “updating” map of the coastal area that draws out the memories of visitors who are allowed to post sticky notes about their past memories of those places, making it a participatory exhibition.

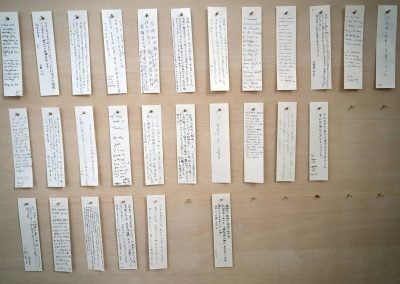

The “Our 3.11” exhibit on the landing of the staircase connecting the first and second floors invites visitors to write their experiences of that fateful day on the front of a strip of paper, and on the back write their wishes for the future, which they hang on the wall. Currently, there are over 800 strips of paper. Each person who stops by plays an important role in ongoing activities to disseminate information.

Today, Sendai tells a story of transformation. It is a city that wears its scars with a quiet dignity, acknowledging the tragedy not as a point of weakness but as a step toward strength. Memorials dot the landscape, not to harrow the soul but to remind and educate.

“To say Sendai has merely recovered would be to miss the essence of our shared journey,” added Yuji. “Yes, the city has rebuilt, but more importantly, it has redefined what it means to rise from the ashes. In the warmth of our community, the resilience of neighbors, and the vibrancy of our streets.”

Sendai beats with a rhythm all its own — one of perseverance, of hope, and of a future reclaimed. In remembering March 11, Yuji said it was important not only to look back, but to look forward. Sendai was not defined by the disaster it endured, but the dreams it has yet to fulfill.

3.11 Exploring Fukushima

- Journey to Japan: A photojournalist’s diary from the ruins of Tōhoku 13 years later

- Timeline of Tragedy: A look back at the long struggle since Fukushima's 2011 triple disaster

- New Year's Aftershock: Memories of Fukushima fuels concern for recovery in Noto Peninsula

- Lessons for future generations: Memorial Museum in Futaba marks 13 years since 3.11 Disaster

- In Silence and Solidarity: Japan Remembers the thousands lost to earthquake and tsunami in 2011

- Fukushima's Legacy: Condition of melted nuclear reactors still unclear 13 years after disaster

- Seafood Safety: Profits surge as Japanese consumers rally behind Fukushima's fishing industry

- Radioactive Waste: IAEA confirms water discharge from ruined nuclear plant meets safety standards

- Technical Hurdles for TEPCO: Critics question 2051 deadline for decommissioning Fukushima

- In the shadow of silence: Exploring Fukushima's abandoned lands that remain frozen in time

- Spiral Staircase of Life: Tōhoku museums preserve echoes of March 11 for future generations

- Retracing Our Steps: A review of the project that documented nuclear refugees returning home

- Noriko Abe: Continuing a family legacy of hospitality to guide Minamisanriku's recovery

- Voices of Kataribe: Storytellers share personal accounts of earthquake and tsunami in Tōhoku

- Moai of Minamisanriku: How a bond with Chile forged a learning hub for disaster preparedness

- Focus on the Future: Futaba Project aims to rebuild dreams and repopulate its community

- Junko Yagi: Pioneering a grassroots revival of local businesses in rural Onagawa

- Diving into darkness: The story of Yasuo Takamatsu's search for his missing wife

- Solace and Sake: Chūson-ji Temple and Sekinoichi Shuzo share centuries of tradition in Iwate

- Heartbeat of Miyagi: Community center offers space to engage with Sendai's unyielding spirit

- Unseen Scars: Survivors in Tōhoku reflect on more than a decade of trauma, recovery, and hope

- Running into history: The day Milwaukee Independent stumbled upon a marathon in Tokyo

- Roman Kashpur: Ukrainian war hero conquers Tokyo Marathon 2024 with prosthetic leg

- From Rails to Roads: BRT offers flexible transit solutions for disaster-struck communities

- From Snow to Sakura: Japan’s cherry blossom season feels economic impact of climate change

- Potholes on the Manga Road: Ishinomaki and Kamakura navigate the challenges of anime tourism

- The Ako Incident: Honoring the 47 Ronin’s legendary samurai loyalty at Sengakuji Temple

- "Shōgun" Reimagined: Ambitious TV series updates epic historical drama about feudal Japan

- Enchanting Hollywood: Japanese cinema celebrates Oscar wins by Hayao Miyazaki and Godzilla

- Toxic Tourists: Geisha District in Kyoto cracks down on over-zealous visitors with new rules

- Medieval Healing: "The Tale of Genji" offers insight into mysteries of Japanese medicine

- Aesthetic of Wabi-Sabi: Finding beauty and harmony in the unfinished and imperfect

- Riken Yamamoto: Japanese architect wins Pritzker Prize for community-centric designs

MI Staff (Japan)

Lее Mаtz

3.11 Exploring Fukushima: The Tōhoku region of Japan experienced one of the worst natural disasters ever recorded when a powerful earthquake was followed by a massive tsunami, and triggered an unprecedented nuclear crisis in 2011. With a personal connection to the tragedies, Milwaukee Independent returned for the first time in 13 years to attend events commemorating the March 11 anniversary. The purpose of the journalism project included interviews with survivors about their challenges over the past decade, reviews of rebuilt cities that had been washed away by the ocean, and visits to newly opened areas that had been left barren by radiation. This special editorial series offers a detailed look at a situation that will continue to have a daily global impact for generations. mkeind.com/exploringfukushima