More than a decade after the devastating events of March 11, 2011, Futaba is cautiously stepping towards rejuvenation. The echoes of the past linger in the abandoned homes and deserted streets, yet there is a burgeoning hope, fostered by initiatives such as the Futaba Project that aim to rejuvenate a sense of community in this area previously stricken by nuclear disaster.

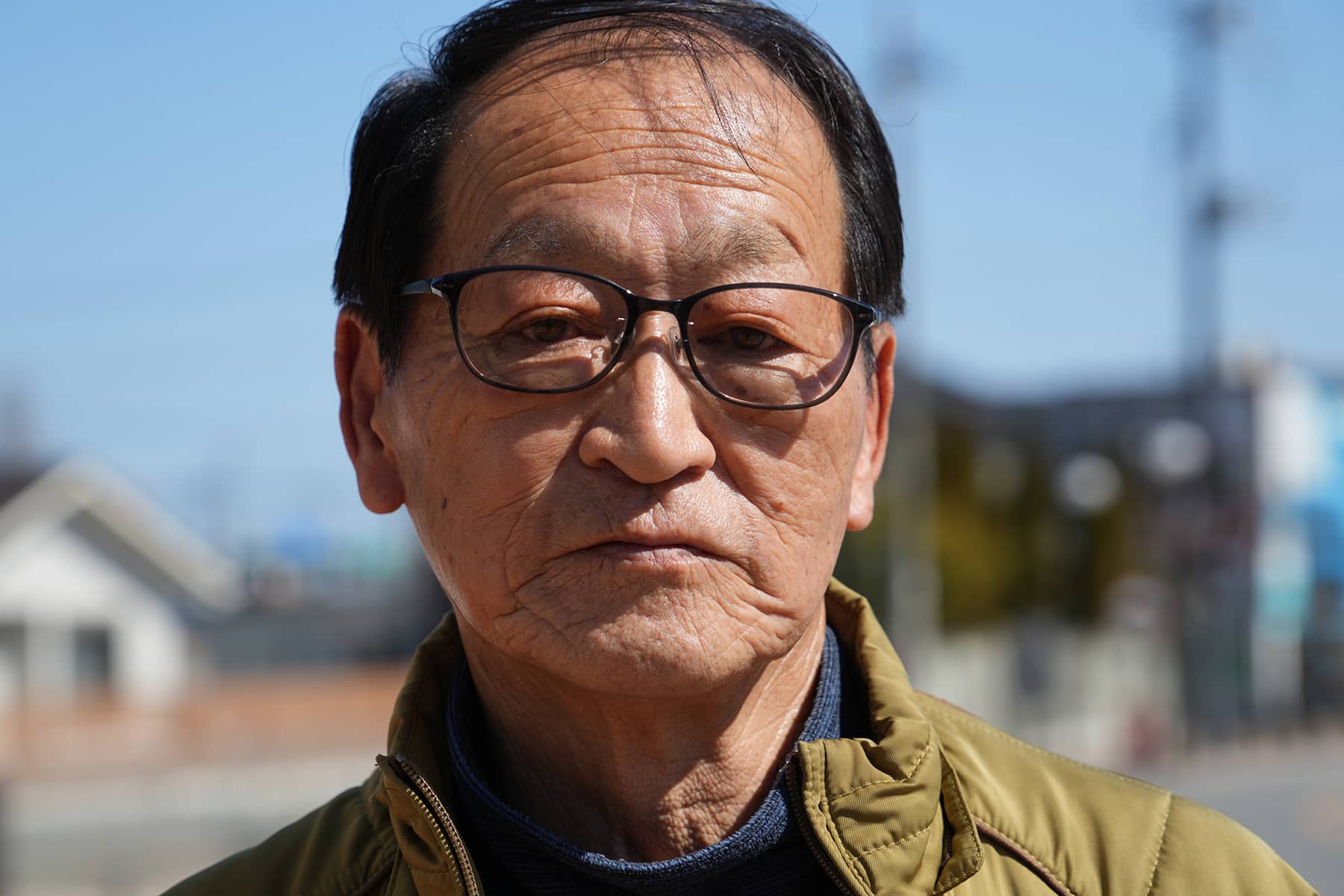

Haruo Imaizumi, a native of Futaba, recounted the immediate chaos and the long, winding road to recovery.

“My ancestors have lived here for generations, and I was born and raised in Futaba Town. When the disaster struck, my family was separated and evacuated to Osaka and Tokyo,” said Imaizumi. “After helping with the restoration work in Futaba Town, I met up with my wife in Tokyo. Living in an unfamiliar Tokyo was difficult, so a month later my wife and I moved to Koriyama City, Fukushima Prefecture.”

Imaizumi said that with decontamination and the passage of time, radiation levels had returned to normal levels. That allowed for evacuation orders to be lifted in some areas. Unfortunately, his home in Futaba was still in a difficult-to-return zone.

The disaster not only ravaged physical structures but also dispersed communities, pushing Imaizumi and his wife to relocate multiple times in search of stability.

Despite the lifting of evacuation orders in parts of the region, the return to a “normal” life in Futaba remained fraught with emotional and logistical challenges.

“More than 10 years have passed since the disaster, and even if we were allowed to go back, we all have new lives and jobs in the places we have moved to,” said Imaizumi. “No one knew if they could return or not. Besides, I don’t want to go back to Futaba Town. There is nothing left for me other than what is left of my home.”

But Imaizumi’s farm, like many other locations, had fallen into disrepair due to being uninhabited for so long. He was not sure if would even return home temporarily if given the opportunity.

Amidst the tangible losses, the beauty of Futaba’s cherry blossoms in Yonomori stands as a poignant reminder of the town’s former vibrancy, according to Imaizumi. This contrast between natural splendor and human abandonment encapsulated the complex journey of recovery and remembrance.

The urgent response in the aftermath of the 3.11 disaster, marked by coming together to aid tsunami victims and navigate the logistical nightmares of identity verification and funerary practices, remains a testament to Futaba’s tight-knit relations.

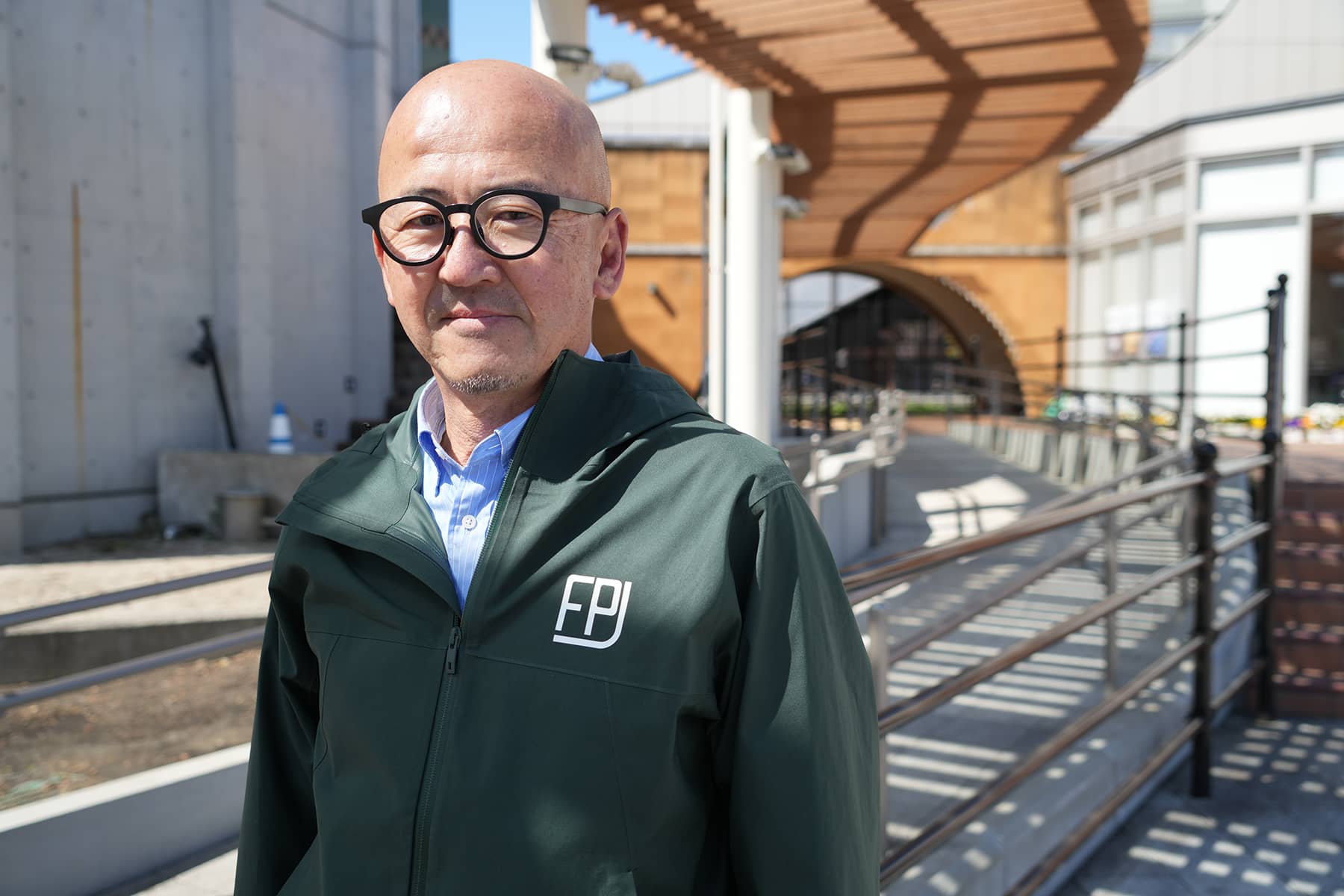

Yuji Muto, representing a newer wave of hope through the Futaba Project, discussed ongoing efforts to revitalize the town and foster a sense of community among both former and potential new residents. Milwaukee Independent caught up with his team while making preparations for a community event on March 11 around the Futaba train station.

“Today we will have a silent prayer and candlelight vigil for the victims of 3-11 in the plaza in front of this place,” said Muto. “The clock on the roof here still points to 14:46, the time of the earthquake.”

As project manager, Muto’s work encapsulates a bridge between the past and the future, aiming to entice families and individuals to partake in the town’s rebirth. However, the challenge is monumental.

“Since the ban was lifted a year ago for parts of Futaba, we have been accepting applications in phases,” said Muto. “Although we have only just begun, we have not received the maximum number of applications.”

Muto added that in addition to health concerns, many who wanted to return also faced psychological barriers to returning.

The Futaba Project, established in March 2019, emerged as a collective endeavor with the purpose of stitching together the fabric of a town torn apart by tragedy. The project’s logo, encircled by an infinity symbol and drenched in rainbow hues, symbolizes enduring hope and the vibrant future envisaged for Futaba.

2024 marks a significant year in the town’s economic recovery, which remains far from complete. The stories of residents, both old and new, have yet to be written. After the government’s 2023 decision to lift certain evacuation orders, there has been a cautious optimism about repopulating and rejuvenating the area.

3.11 Exploring Fukushima

- Journey to Japan: A photojournalist’s diary from the ruins of Tōhoku 13 years later

- Timeline of Tragedy: A look back at the long struggle since Fukushima's 2011 triple disaster

- New Year's Aftershock: Memories of Fukushima fuels concern for recovery in Noto Peninsula

- Lessons for future generations: Memorial Museum in Futaba marks 13 years since 3.11 Disaster

- In Silence and Solidarity: Japan Remembers the thousands lost to earthquake and tsunami in 2011

- Fukushima's Legacy: Condition of melted nuclear reactors still unclear 13 years after disaster

- Seafood Safety: Profits surge as Japanese consumers rally behind Fukushima's fishing industry

- Radioactive Waste: IAEA confirms water discharge from ruined nuclear plant meets safety standards

- Technical Hurdles for TEPCO: Critics question 2051 deadline for decommissioning Fukushima

- In the shadow of silence: Exploring Fukushima's abandoned lands that remain frozen in time

- Spiral Staircase of Life: Tōhoku museums preserve echoes of March 11 for future generations

- Retracing Our Steps: A review of the project that documented nuclear refugees returning home

- Noriko Abe: Continuing a family legacy of hospitality to guide Minamisanriku's recovery

- Voices of Kataribe: Storytellers share personal accounts of earthquake and tsunami in Tōhoku

- Moai of Minamisanriku: How a bond with Chile forged a learning hub for disaster preparedness

- Focus on the Future: Futaba Project aims to rebuild dreams and repopulate its community

- Junko Yagi: Pioneering a grassroots revival of local businesses in rural Onagawa

- Diving into darkness: The story of Yasuo Takamatsu's search for his missing wife

- Solace and Sake: Chūson-ji Temple and Sekinoichi Shuzo share centuries of tradition in Iwate

- Heartbeat of Miyagi: Community center offers space to engage with Sendai's unyielding spirit

- Unseen Scars: Survivors in Tōhoku reflect on more than a decade of trauma, recovery, and hope

- Running into history: The day Milwaukee Independent stumbled upon a marathon in Tokyo

- Roman Kashpur: Ukrainian war hero conquers Tokyo Marathon 2024 with prosthetic leg

- From Rails to Roads: BRT offers flexible transit solutions for disaster-struck communities

- From Snow to Sakura: Japan’s cherry blossom season feels economic impact of climate change

- Potholes on the Manga Road: Ishinomaki and Kamakura navigate the challenges of anime tourism

- The Ako Incident: Honoring the 47 Ronin’s legendary samurai loyalty at Sengakuji Temple

- "Shōgun" Reimagined: Ambitious TV series updates epic historical drama about feudal Japan

- Enchanting Hollywood: Japanese cinema celebrates Oscar wins by Hayao Miyazaki and Godzilla

- Toxic Tourists: Geisha District in Kyoto cracks down on over-zealous visitors with new rules

- Medieval Healing: "The Tale of Genji" offers insight into mysteries of Japanese medicine

- Aesthetic of Wabi-Sabi: Finding beauty and harmony in the unfinished and imperfect

- Riken Yamamoto: Japanese architect wins Pritzker Prize for community-centric designs

MI Staff (Japan)

Lее Mаtz

3.11 Exploring Fukushima: The Tōhoku region of Japan experienced one of the worst natural disasters ever recorded when a powerful earthquake was followed by a massive tsunami, and triggered an unprecedented nuclear crisis in 2011. With a personal connection to the tragedies, Milwaukee Independent returned for the first time in 13 years to attend events commemorating the March 11 anniversary. The purpose of the journalism project included interviews with survivors about their challenges over the past decade, reviews of rebuilt cities that had been washed away by the ocean, and visits to newly opened areas that had been left barren by radiation. This special editorial series offers a detailed look at a situation that will continue to have a daily global impact for generations. mkeind.com/exploringfukushima