I have written many times over the years about faith, and navigating the world while holding onto what we believe. The wave of mass shootings altered conversations about faith, in acknowledging America’s addiction to gun violence. The full-scale invasion of Ukraine last year did not force me to re-examine my faith, but I had a reason to finally articulate and share unspoken aspects of it.

In those personal essays I shared more about my Jewish heritage, and how even as a youth growing up in the 1980s my family was forced to hide all mention of being Russian Jews from Ukraine. My guide for understanding Jewish culture from “the old country” could be summarized by watching Norman Jewison’s 1971 classic “Fiddler on the Roof.” My grandparents never talked about their life before America, no matter how persistently I asked during holidays in Baltimore.

My first reckoning with Judaism came when I studied for my Bar Mitzvah, while staying with my grandparents for the summer. My family never expected my commitment to being Jewish, and maybe I first had the idea as an act of rebellion. But at the time, the structure of the religion made more sense to me than the bitter version of Christianity I was surrounded by in Georgia, or the indifference to God from my family in Milwaukee.

Every day while friends back home were enjoying the recreations of summer, I was stuck in a hot school without air conditioning as I studied Hebrew and the scriptures with my Rabbi, who was Orthodox. One day when I was leaving the Temple, I encountered a younger boy with side curls. I asked my grandfather about him later, and was told that the boy was a Hasidic Jew.

“They are more Orthodox than we are,” he said. I remember replying something like, “More Orthodox than Orthodox? What could be more Orthodox than not putting cheese on hamburgers, or pepperoni on pizza?” To the mind of a 13-year-old influenced by mainstream American culture, a kosher kitchen was a punishment.

In the years that followed, I never again had a close connection with any Jewish communities. There were none where I lived, and I had also moved on with my personal faith. What I was exposed to, mostly through movies and news reports, was the Hasidic community. Or as I would describe them in my youth, as the really Orthodox Orthodox.

But they were always presented as caricatures, stereotyped Jews taken from a cartoon version of “Fidler on the Roof” and missing the charm of being a musical.

For my first assignment to cover the war in Ukraine for Milwaukee Independent last May, I did not have time to explore Krakow and its Jewish history. But opportunity and inspiration did allow me to explore Babyn Yar in Kyiv and Berezhany in Ternopil Oblast.

Having lost family in the Holocaust, I was eager to visit historic Jewish memorial sites in Ukraine. And I was also determined to bring more attention to the fact that “Never Again” was actually happening again.

To say that Jewish history and Ukrainian culture is complicated would be an epic understatement. But it is the most simple truth. So when I agreed to join a delegation from Milwaukee on a humanitarian mission to Ukraine in June and July, I researched the areas on the itinerary where I had not previously visited. The city of Uman stood out for that reason.

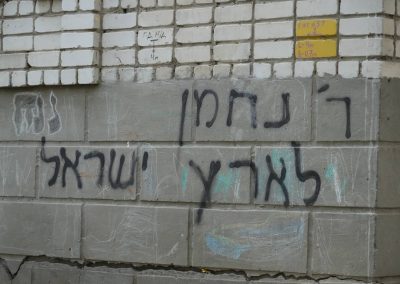

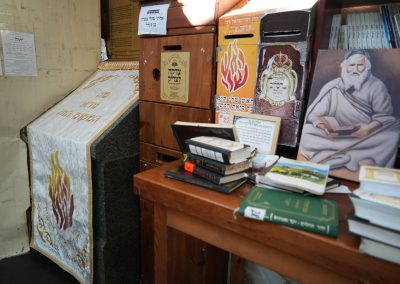

Located in central Ukraine, Uman has one of the largest and most vibrant Jewish communities in the country. It is also the final resting place of the Rabbi who is credited with the Breslov movement of Hasidic Judaism. Thousands of Hasidic Jewish pilgrims flock there each September to mark the Jewish New Year, Rosh Hashanah.

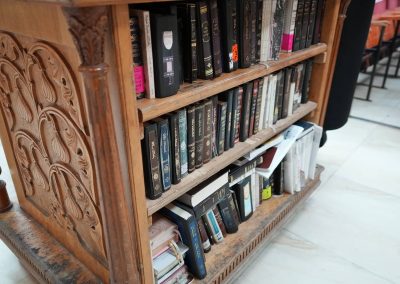

Many books have been written about Reb Nachman of Bratslav, and about Hasidic Jews. I am not qualified to explain much about either – and with the required level of respect they are due, beyond what I can google. But I can share my experience as a Jewishish outsider visiting a Holy Jewish site. Which is to say, it was a wonderful experience that I will cherish. But there was so much meaning that was lost to me.

I mention this because it is another example of the depth of racism that people remain unaware of. My Jewish heritage was denied to me by White Nationalists who embraced fascist and anti-Semitic ideology in the community where I spent time in my youth.

It does not matter that I am not Jewish now, and I am not saying that I would be Jewish if I had been able to immerse myself in Jewish culture. But I was robbed of the choice to experience that rich heritage and its social connections.

I learned to read and speak Hebrew, but today I feel closer to Japanese and Islamic cultures. I took the paths that were open to me, and knocked down the ones that were not. But being Jewish, no route existed for me to consider after I graduated middle school. That loss is an unseen cost of racism in America.

After visiting Jerusalem for the first time in my life only a few months ago, the Jewish quarter of Uman felt a bit like a tourist town. It was also an abrupt experience to be driving through the typical Ukrainian countryside, and then turning the corner into what looked like a snapshot from my family’s photo album of Jewish Baltimore in the 1950s.

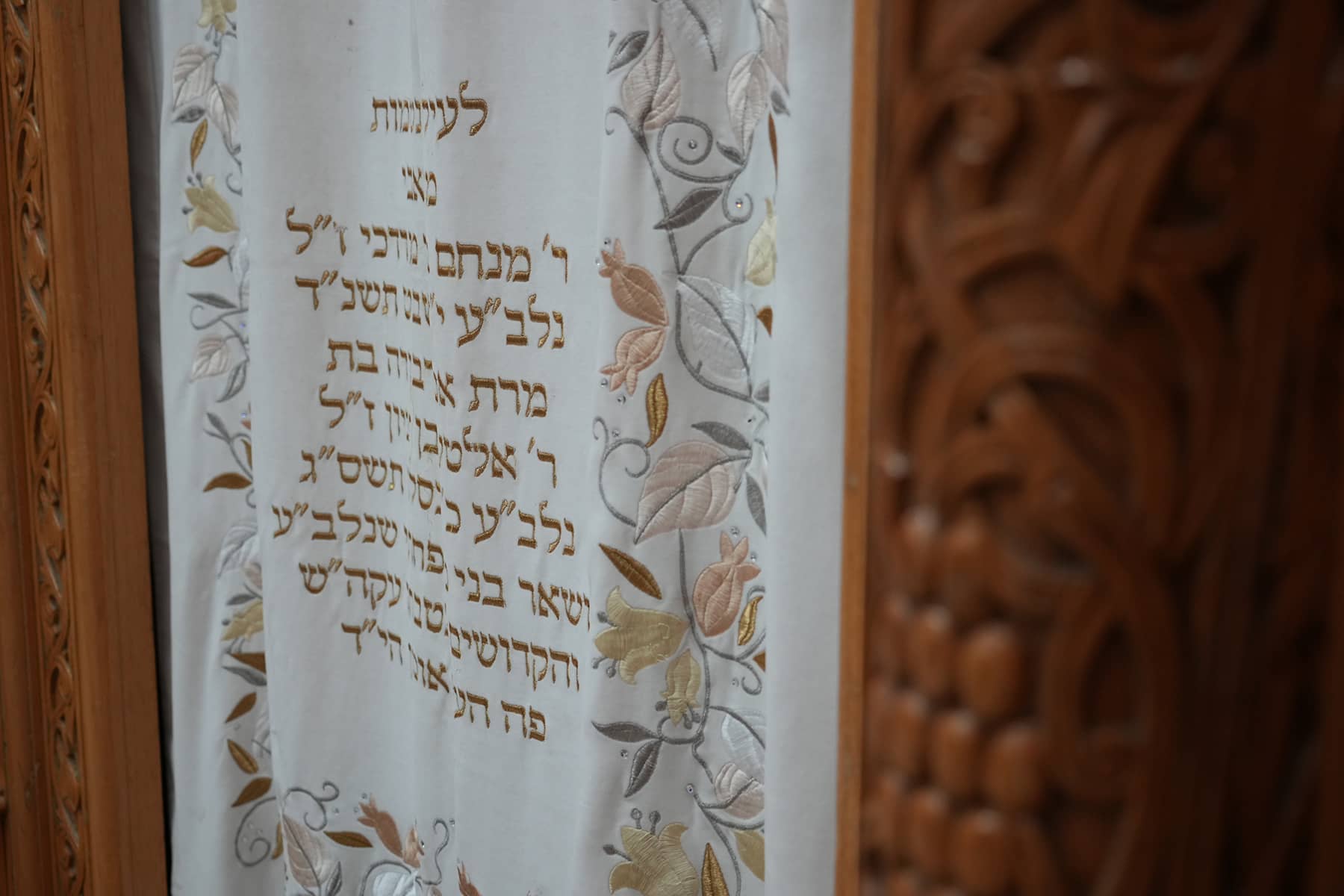

I was not able to experience the robust Jewish culture, or how it celebrated holidays, because of the timing of my visit. Neither the COVID-19 pandemic nor the full-scale invasion had previously diminished pilgrims from visiting the city. But as I walked along the streets and experienced the Nachman of Breslov’s tomb for myself, I could feel the weight of its rich culture, even if life had prevented me from appreciating its fullness.

“A large Jewish community lived in Uman in the 18th and 19th centuries. During the Second World War, the Battle of Uman took place in 1941. The German Army deported the entire Jewish community, murdering an estimated 17,000 Jews. The Jewish cemetery was completely destroyed, including the burial place of Rebbe Nachman of Breslov. After the war, a Breslov Hasid managed to locate the Rebbe’s grave and preserved it when the Soviets turned the entire area into a housing project. Since the 1990s there has been a small, but growing Jewish population in Uman, concentrated around Rebbe Nachman of Breslov tomb on Pushkina Street.” – Wikipedia

I am still processing what my visit means to me. I am stronger in my faith today because of my Jewish background, but also from the other religions I explored along my spiritual journey. When I returned to Milwaukee from Japan after a decade, because the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami had left me homeless, most people who met either asked if I was a missionary or a Buddhist.

In truth, this essay is more about my limited experience with Uman’s Jewish community than it is explaining about it. But I can pay tribute to that heritage from my perspective, which is something that is not detailed on Uman’s Wikipedia page. My hope is that through these words and the companion images, others will be inspired to learn more. And perhaps, find the courage to express their own heritage.

To unravel a long and complicated history begins simply by pulling one loose thread.

Series: Return to Ukraine

- Return to Ukraine: A trauma loop of travel from Milwaukee to a country still at war a year later

- From Weddings to War: How Kostiantyn and Vlada Liberov photograph Ukraine's daily horrors

- Being Friends of Angels: The Milwaukee nonprofit saving lives and offering hope in Ukraine

- Mayors of Milwaukee and Irpin expand Sister City cooperation after visit by nonprofit delegation

- Interview with Tom Barrett: U.S. Ambassador to Luxembourg reflects on forging ties with Irpin

- Wisconsin Ukrainians host annual fundraising picnic to support homeland on 500th day of war

- Advanced Wireless to donate 840 access points to rebuild Irpin's citywide Wi-Fi network

- Children of Irpin begin planning mural for Mitchell Airport to showcase Sister City friendship

- Irpin is not forgotten: Residents thank Milwaukee Independent for reporting on their "Hero City"

- Milwaukee photojournalist on assignment in Kyiv during July 2 Russian drone strike targeting civilians

- Russian cruise missile attack kills residents far from front lines in Western Ukraine city of Lviv

- Ukraine arrests man accused of directing Russian ballistic missile strike on Kramatorsk pizza parlor

- Milwaukee offers Ukrainian refugee family life-saving treatment for son's genetic condition

- Nikita Pirnach: Irpin student hopes to help his country after finishing education in Milwaukee

- Sick children wait for overseas medical treatments as a new generation is born in Ukraine during war

- Iryna Suslova: The superwoman saving Ukrainian children abducted by Russia

- How a group of Ukrainian mothers, wives, and daughters are distributing vital humanitarian aid

- Freeing Freddie: Educational program aims to reduce PTSD for Ukraine's war-weary children

- The trauma of living: When being killed is the preferred choice to being disfigured from battle

- President Zelenskyy offers gratitude and awards to wounded soldiers while visiting Lviv Hospital

- Former Vice President Mike Pence visits Irpin during unannounced campaign trip to Kyiv

- Military Hospitals provide vital care for Ukrainian soldiers in need of hope and healing

- Combat surgeons pioneer advances in maxillofacial reconstruction of Ukraine's injured heroes

- Milwaukee donors cover cost of reconstructive surgery for American volunteer wounded in battle

- In their own words: Listening to the Voices of Children talk about their experiences from war

- Traumatized by War: Children of Ukraine carry on after losing parents, homes, and innocence

- Widespread Torture: U.N. report documents Russia's systematic executions of Ukrainian civilians

- Wisconsin volunteers sort and pack donated medical supplies for use in Ukraine's hospitals

- Lviv warehouse serves as vital link in medical supply chain from Milwaukee to frontlines

- Aid from Milwaukee is providing internally displaced people in Ukraine with food and clothing

- Iryna Pletnyova: How the city of Uman transformed into a hub for refugees fleeing war

- Bombs in the night: Why children in Uman are still traumatized by Russia's missile attack

- School Bunkers: When a national flag becomes a memorial to dead Ukrainian students

- Hasidic life in Uman: A journey across Ukraine to the Tomb of Rabbi Nachman of Breslov

- Tetiana Storozhko: Being a witness to the history of Roma culture in Ukraine

- Remembering Oskar Schindler: A photojournalist’s diary from the streets of Jewish Kraków

Lее Mаtz

Svitlana Niko, Nazar Gonchar, Vitaliy Holovi, Amateur007, ReX977, and Paparazzza / Shutterstock

Milwaukee Independent has reported on Russia’s brutal full-scale invasion of Ukraine since it began on February 24, 2022. In May of 2022, Milwaukee Independent was the first news organization from Wisconsin to report from Milwaukee’s Sister City of Irpin after its liberation. That work has since been recognized with several awards for journalistic excellence. Between late June and early July of 2023, Milwaukee Independent staff returned to Ukraine for a second assignment to report on war after almost a year. The editorial team was embedded with a Milwaukee-based nonprofit, Friends of Be an Angel, on a humanitarian aid mission across Ukraine. For several weeks, Milwaukee Independent documented the delivery of medical supplies to military and civilian hospitals, and was a witness to historic events of the war as they unfolded.

Return to Ukraine: Reports about a humanitarian mission from Milwaukee after a year of war