By Joshua F.J. Inwood, Associate Professor of Geography Senior Research Associate in the Rock Ethics Institute, Pennsylvania State University; and Derek H. Alderman, Professor of Geography, University of Tennessee

Delays and long lines at polling places during recent presidential primary elections represent the latest version of decades-long policies that have sought to reduce the political power of African Americans in the United States.

Following the Civil War and the extension of the vote to African Americans, state governments worked to block black people, as well as poor whites, from voting. One way they tried to accomplish this goal was through poll taxes – an amount of money each voter had to pay before being allowed to vote. This practice was abolished by the passage of the 24th Amendment in 1964. Further protections for nonwhite voters came with the Voting Rights Act, which closely followed the Selma to Montgomery civil rights protest marches 55 years ago, in March 1965.

But in recent years, new barriers have gone up that, we believe, constitute a new type of poll tax on working people and minority voters. We are scholars of the American civil rights movement, including the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee’s voting rights efforts. Unlike past poll taxes, the modern poll tax isn’t paid in money, but in time – how long it takes a person to get to a polling place, and, once there, how long it takes for them to actually cast their ballot.

Securing the right to vote

Almost immediately after the 15th Amendment gave African Americans the right to vote in 1870, state governments in the South passed a series of laws seeking to limit freed blacks’ voting power. In addition, white supremacist organizations like the Ku Klux Klan used violence to intimidate African Americans from casting ballots. This situation remained largely unchallenged for almost a century, until the 1960s, when the years of protest by the civil rights movement bore fruit in the abolition of poll taxes and federal protection of citizens’ voting rights.

Creating a new poll tax

Since the 1960s, there have been efforts by state and local officials to limit these hard-won victories. The most recent chapter in this battle is the 2013 Supreme Court decision in Shelby County v. Holder, which lifted restrictions on states that have historically blocked African Americans from voting, so state governments no longer need to seek federal approval before taking actions that might disproportionately harm black citizens’ right to vote. Since the Shelby County decision, local election boards and state governments have closed over 1,600 polling places. That is approximately 8% of total voting locations within jurisdictions affected by the Shelby decision.

The U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, a bipartisan independent study group started in 1957, found that states claimed polling-place closures were intended to save money, centralize voting operations, and complying with Americans with Disabilities Act – but really the goal was reducing voter turnout, particularly among minority voters who were historically disenfranchised. Using publicly available data, federal lawsuits brought against states and counties the report documents clear patterns of discrimination.

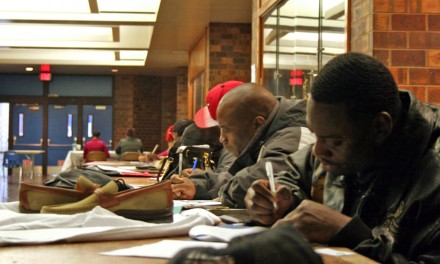

These closures, often done with little notice or public accountability, have occurred across communities of varying racial and demographic characteristics. What unites these places are the costs they impose on voting – from longer wait times to transportation obstacles – experienced disproportionately by voters of color, older voters, rural voters, voters with disabilities and poor working people in general.

In the 2016 election, for instance, scholars at UCLA found that voters in black neighborhoods waited, on average, 29% longer to vote than voters in predominantly white communities. The study found, “Even within the same county, voters in a hypothetical all-black precinct would wait 15 percent longer than voters in an all-white precinct.”

The study found voters in majority black precincts were far more likely to wait longer than half an hour to cast a ballot than voters in majority white precincts. A study of the 2012 election found that the voters who waited in long lines paid, collectively, over half a billion dollars in lost wages.

Considering time

We believe that polling place closures represent a modern-day version of the poll tax. In our view, access to polling places is a key element of citizens’ right to vote. People need fair and equitable access to places to vote – and determining what that means should include time and travel costs imposed on voters.

This would expand traditional understandings of access to polling places beyond narrow legal opinions and take into account the full range of racial and class barriers to being able to participate in U.S. democracy. Everybody’s time is valuable. But wait times have different effects depending upon a person’s socioeconomic status.

Working people calculate daily how much time, if any, they can afford to be away from their hourly wage job. Interminable waits at polling places may not fit in the schedule with a second or third job. Work supervisors may not excuse a late arrival or an absence. A working person may feel pressure to leave a polling place before casting a ballot, just to get to work on time and keep the money coming in.

Importantly, the Supreme Court’s Shelby County ruling did not invalidate all of the Voting Rights Act. Rather, it threw out the method by which the federal government could determine which areas of the country had policies that resulted in widespread voter disenfranchisement.

Congress could enact new legislation detailing a new method of making that determination, which would then restore federal oversight to states that create barriers to voting. However because of our federal system where states have direct oversight of elections many of these decisions ultimately take place at the local and state level.

As a result, election officials need to work in transparent ways with diverse communities to ensure that changes to voting locations do not disproportionately limit minority access. In addition, states could also ensure equal access to voting by creating, or expanding, early voting periods, and making it possible to vote by mail.

Rіngо H.W. Chіu

Originally published on The Conversation as Closing polling places is the 21st century’s version of a poll tax

Support evidence-based journalism with a tax-deductible donation today, make a contribution to The Conversation.