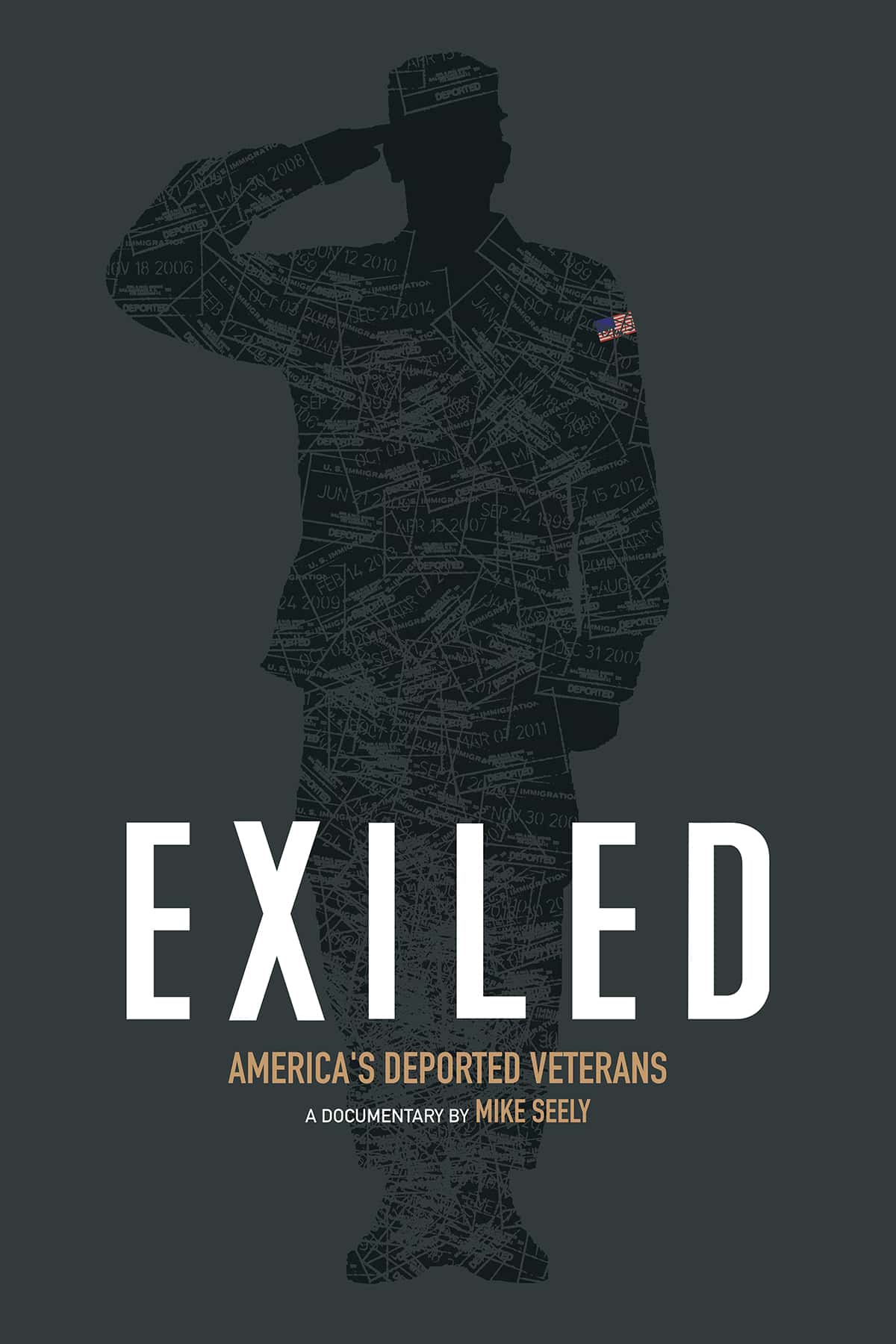

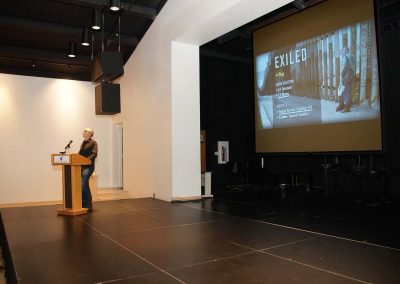

Forward Latino and UWM MAVRC hosted a special community screening of the Mike Seely documentary “Exiled: America’s Deported Veterans” at the United Community Center on October 8, featuring a talkback session with the director after the film.

“Exiled” tells the stories of two US military veterans who were honorably discharged and deported Mexico. As a former paratrooper, Hector Barajas is on a mission to raise awareness about the deported veteran issue, and reunite with his daughter in Compton, California. Army veteran Mauricio Hernandez struggles with severe PTSD as a result of his time fighting in Afghanistan, but in Tijuana, Mexico he has no access to the mental health care he is entitled to as a veteran.

Based in the San Francisco Bay Area, Mike Seely is an award-winning filmmaker with the career experience of working on cross-cultural and international projects. He first learned about the deported veterans situation in 2015 from his wife, who had been to Tijuana on another project.

“She met Hector at a public park by the border, where sometimes families can visit. He was passing out pamphlets, and gave one to my wife,” said Seely. “She brought the pamphlet home and I just called the number on it to learn more. Hector and I eventually struck up a friendship over the phone, so I spoke to my co-producer and editor. Together we decided to tell this story as an independent film from the perspective of deported veterans. Back in 2015, there really wasn’t much media attention about it.”

Since 1996, the United States government has been deporting veterans who, as legalized citizens, joined the Armed Forces and served their country. Green Card holders can serve in U.S. military but are not automatically guaranteed citizenship. The path to citizenship has been a murky policy of misinformation from the recruitment process to expectations upon discharge.

Yet under every presidential administration since Clinton, the government has continued to deport combat veterans, legal residents of the United States, while enticing them with the prospect of citizenship. If these men have not earned United States citizenship, who has?

“What stuck with me more than anything was just really having my eyes opened to what it’s like to not only be a veteran, but to be a veteran and have your country turn its back on you,” said Seely. “I had to constantly challenge my my assumptions, about what it was like to be a veteran, to be somebody living with PTSD, and to be a deportee in the first place who is separated from family.”

These soldiers were willing to die for their country, and are now fighting to be heard, and return to America, the country they consider home. Seely’s documentary highlights how America has abandoned these combat veterans without regard for their wartime service.

It is widely known that PTSD affects returning service personnel, and that getting treatment for their condition from the Department of Veterans Affairs can be a challenge. Being deported prevents these veterans from obtaining the medical care they desperately need from the VA, which they are entitled to.

“I came away from making the film with a feeling and understanding that no matter what the technical conviction was in the court system or in the immigration system, that there is a level of denial of humanity that is going on with most of these folks that doesn’t seem right,” said Seely. “So to me, it’s hard to reconcile the situation after in seeing so many of these stories firsthand and meeting the people on the ground.”

“Exiled” has been featured at film festivals across the country, and has transitioned into a tool for educational outreach with screenings at local community centers. Plans are underway to eventually broadcast the documentary nationally on PBS.

“My hope is that people are open enough to hear and try to experience these stories, and see the situation from the point-of-view of the people that are portrayed in the film,” said Seely. “I feel like that’s the starting point. That’s how we can start a conversation. So as long as people come with open eyes, ears, and hearts, then that’s a good place to start.”

The 1996 Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996 (IIRIRA) expanded the list of deportable offenses. In reality, it converted what had been common misdemeanors, such as illegal substance possession, and expanded them to the level of a felony in Federal Court. Even shoplifting, considered a misdemeanor in many states, became grounds for deportation.

The law also removed the power of discretion from judges in determining a judicial remedy. Before 1996, a judge could take a veteran’s record into account. Lost was any regard for rehabilitation or redemption, with the individual deported for life without question or review.

Deported veterans can only seek a humanitarian parole, but it is almost never granted. On the occasions when it has been, the individuals were literally days away from dying. Otherwise, that condition is the only way these veterans can return to America – in a box. They retain the right to be buried at a national cemetery, and the VA even pays for the headstone.

Barajas started the Deported Veterans Support House (aka The Bunker) to support deported veterans on their path to self-sufficiency, by providing assistance with food, clothing, and shelter as they adjust to life in their new country of residence. The organization also advocates for political legislation which would prohibit the deportation of past and present military service personnel.

“It’s been a fascinating journey unlike any other documentary project I’ve been involved in – a real learning experience. I had to dive into a world where I’m not a veteran or an immigrant myself,” added Seely. “But I had a gut feeling that there was something wrong about the United States deporting people who had risked their lives for the country.”

Legislation could be approved to safeguard green card veterans by fast tracking naturalization, issue temporary re-entry visas so they can complete the process, and provide better information for non-citizen service personnel, but several bills previously introduced to protect veterans from deportation have already failed to pass.

Research done by the ACLU focused on 38 veterans who served in designated periods of hostility. They were deported to countries such as Ecuador, India, Philippines, Mexico, Canada, Senegal, El Salvador, Honduras, Portugal, Jamaica, Panama, Costa Rica, Uruguay, Italy, Dominican Republic, Peru, Haiti, Germany, Guyana, Trinidad and Tobago, and Panama.

14

Vietnam Era

February 28, 1961 – October 15, 1978

11

Desert Storm Era

August 2, 1990 – April 11, 1991

13

Enduring Freedom Era

September 11, 2001 – Present

1.6 Million Family Separations

As a result of the 1996 laws, it is estimated that more than 1.6 million family members were separated by deportation between 1997 and 2007. That is a rate of 438 family members daily.

460,000 Children without a Parent

The harsh deportation policies of the last 20 years have resulted in an entire generation of children growing up with at least one parent. In the first six months of 2011, almost a half million parents of U.S. citizen children were deported, which put thousands of children into the foster care system.

© Photo

Lee Matz, Mike Seely, and Hector Barajas