After the Milwaukee Brewers honored Negro Baseball League players during a special Tribute Game at the Miller Park Stadium on June 25, the Negro League Experience continued immediately afterward at the Hyatt Regency Hotel downtown.

“I saw this as an opportunity to bridge the gap of apathy of baseball’s historical significance in our culture as African-Americans, and the absolute disregard toward the sport in our communities,” explained Patrice Smith, who organized the event. ”I contacted the Yesterday’s Negro League President, Dennis Biddle, who expressed the same sentiments and agreed to join me in my endeavors to save our youth through Bridging Gaps To Greatness.”

Smith began Bridging Gaps to Greatness (BGG) as a violence prevention program to support and train youth 4 to 15 in areas of academic achievement, athletic sportsmanship, leadership development, and inspiration by learning to reassert a sense of hope in the future that awaits them.

“I have found it very unfortunate, that sometimes it takes a tragedy to remind you of what’s really important in life,” Smith said, referring to February 24, 2012 when she lost her son to gun violence at the age of 21.

The Negro League Experience began with a meet-and-greet session of well known athletes who played in the Negro League Baseball, and the men shared their experiences playing America’s greatest past-time. Fans were able to get autographs of the legendary sports figures, a group with dwindling numbers each year due to old age. The following Questions & Answers panel was moderated by Earl Arms, Sports Anchor from Channel 58 TV.

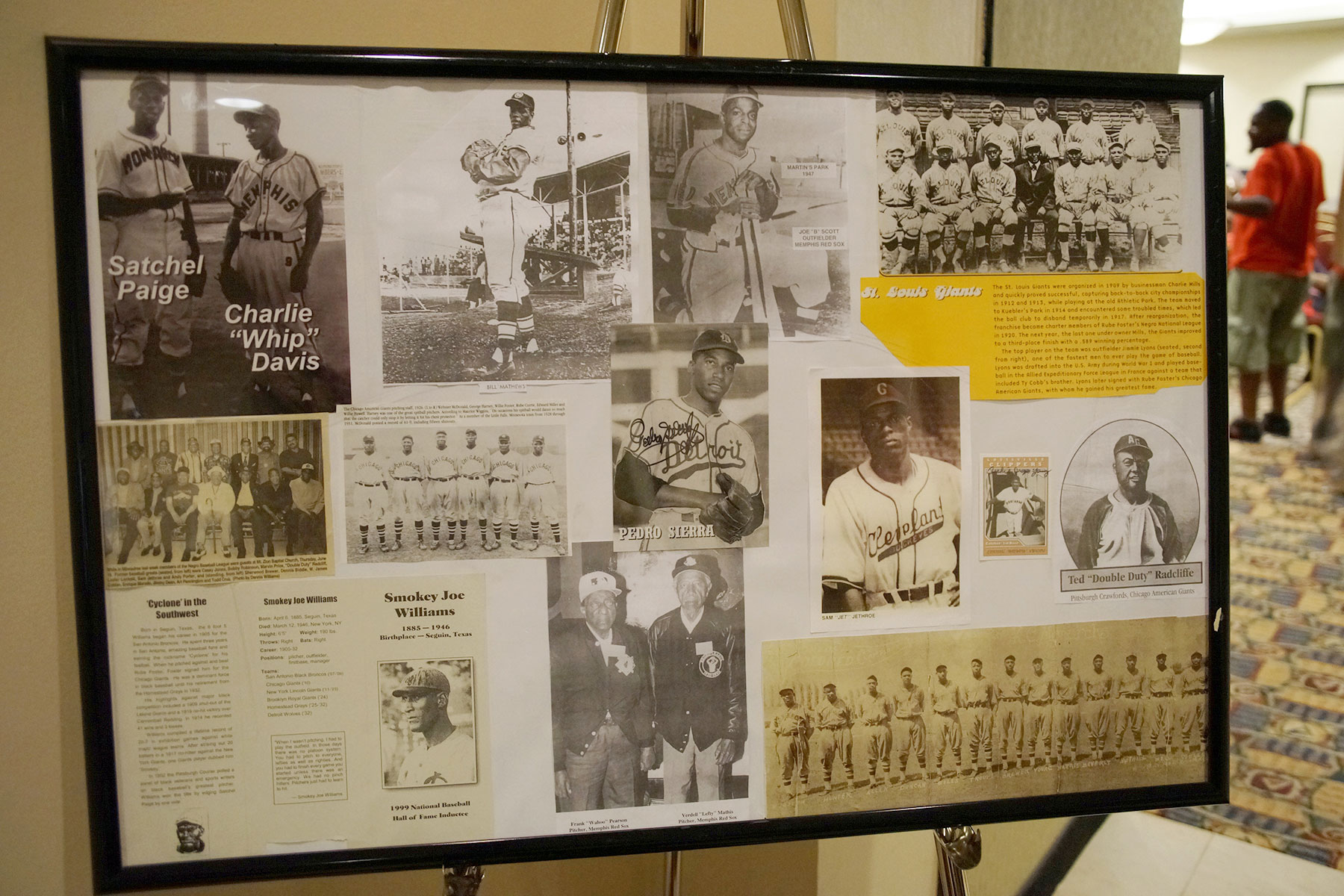

A traveling exhibit was on display, which presented photographs, documents, and memorabilia as a glimpse into the game’s history. It was part of the fundraising event’s effort, along with the Beckum Little League Foundation, to draw awareness of a forgotten chapter in the sport and help the former players in their retirement years.

“My second professional game was in Racine, Wisconsin. I pitched against a player by the name of Gerald “Lefty” McGinnis. I didn’t know about him since I was only 17 years old, but Gerald had been in the league a long time. He was one of the legendary pitchers in the Negro League, and I beat him, I won the game,” said Dennis Biddle. “I learned that he was one of the few players who ever beat Satchel Page. Page was known as The Man. So that night after the game I was named the The Man Who Beat the Man Who Beat the Man.”

Now a retired social worker, the former Negro League Baseball player Dennis “Bose” Biddle was born on June 24, 1935, in Magnolia, Arkansas and has lived in Milwaukee since 1958. In 1996, Biddle founded the organization, Yesterday’s Negro League Baseball Players LLC to support the surviving members of the Negro League baseball teams and defend their economic interests. The highlight of his life was a 1955 dinner with Jackie Robinson.

“At dinner in downtown Chicago, I sat across from him and asked, ‘Mr. Robinson, did you ever think about quitting?’ He said, ‘Every day, kid, but I made a promise to open the door so other young black men could play in the Major League.’ And today,” said Biddle, “there are players in the sport who don’t even know who Jackie Robinson was.”

Robinson’s character, his use of nonviolence, and his unquestionable talent challenged the traditional basis of segregation which then marked many other aspects of American life. He had an impact on the culture of and contributed significantly to the Civil Rights Movement. It was common for most people of the day to think that the Negro League was the Minor League organization of White baseball.

“The Negro League players were stars when they arrived in the White Major League, after Jackie Robins broke the color line,” said James Cobbins. “Satchel Paige played for the Cleveland Indians in 1948. He was named Rookie of the Year. That year, the team won the Pennant and the World Series. They have not won it since.”

The Negro Leagues were professional baseball leagues formed by teams predominantly made up of African-Americans. The term came to be used broadly to include professional black teams outside the leagues, and most commonly for the seven relatively successful leagues beginning in 1920 that are sometimes referred to as the “Negro Major Leagues.” The Negro American League of 1951 is considered the last major league season and the last professional club, the Indianapolis Clowns, operated as a humorous sideshow rather than competitively from the mid-1960s to 1980s.

As Biddle speaks to groups around the country, he is often confronted for using the term Negro League instead of African-American. He explains that he has to use the historical context to describe how things happened because “when the League started we were called Negros. It existed from 1920 to 1960 and produced some of the best baseball players ever. A lot of them would have been Hall of Famers if they had been given the opportunity.”

One of those legends, William McCrary, was offered a spot after his tryouts, but he wanted to stay in Beloit and finish high school. When he did join, “Satchel Page pulled all the guys together and told them, now we have some Young Blood,” said McCrary. “And that was my nickname from then on.”

“I played with three teams, the Chicago American Giants, the New Orleans Eagles, and the Hardwood Sports in Baton Rouge, Louisiana,” said Ray Knox. “I traveled all the way, Canada and everywhere, and my nickname was ‘Boo Boy.’ I was playing one team, then I left that team for another one. So when I played against my original team, the manager said ‘I want ya’ll to boo that boy.’ That’s the way I got the name, and I kept it all the way through every team I played with.”

Often clouded in myth, the truth was that blacks played in Major League baseball before they were segregated from the sport, and Jackie Robinson was not truly the first black player. In September 1887, eight members of the St. Louis Browns, who eventually became the St. Louis Cardinals, staged a mutiny during a road trip, and refused to play a game against the New York Cuban Giants, a prominent Colored team of the era. Newspapers of the day reported that, “for the first time in the history of baseball the color line has been drawn, and that by the St. Louis Browns, who have established the precedent that white players must not play with colored men.”

Also in 1887, a white player on the Syracuse team of the International League refused to pose for the team picture because of a black teammate. In response, the International League owners decided to discontinue signing African Americans, though they permitted existing players to remain on the teams. Shortly afterwards, the American Association and the National League both unofficially banned African-American players, making the adoption of racism in baseball complete. By 1890, the International League was all white, as it would remain until 1946, when Jackie Robinson played for the Montreal Royals.

A 2003 Gallup Poll showed the percentage of African-Americans that considered baseball as their favorite sport to watch declined from about 43 percent in 1960 to 5 percent. The percentage of blacks who said they watched baseball at all declined from 52 percent in the early 1950s to 33 percent in the early 2000s.

“I noticed it in 1950, I’m 81 years old so I was 15 then, that Black kids were persuaded not to play baseball,” said Reggie Howard. “We were systematically taught in the school I went to that you had to participate in Track & Field. That’s the sport all the black kids were shifted to, so there was one sport the white kids could control, which was baseball.”

Major League Baseball has actually begun to investigate the decline of blacks in baseball. Trends point to flawed youth programs which focus on money. Little League baseball in local communities has become a business enterprise designed to exclude those without the means and mobility to participate. The expansion of pay-for-play teams in youth baseball over the past two decades, and parents willing to write checks that fund coaches and equipment, has had a negative impact on African-American participation.

“What made me become a good hitter was when I was a real young boy, we used to get broom handles and go to grocery stores and get soda water caps,” said Roosevelt Jackson, the oldest living player and grandson of a slave from Georgia. “At night we would go to a street corner where there was a light, and play strike each other out. I was hard to strike out.”

Jackson was inducted into the Yesterday’s Negro League Wall of Fame on June 26 along with Knox and McCrary. The special ceremony was held following service at Holy Redeemer Church of God in Christ (COGIC), at the Mother Kathryn Daniels Center. More retired Negro League players are scheduled for induction in 2017.