George Banda traveled from Milwaukee to Washington DC for Veterans Day 2017 events. Along his journey, he visited many of his fallen friends by paying tribute to their names on The Wall, the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, and their graves at Arlington National Cemetery.

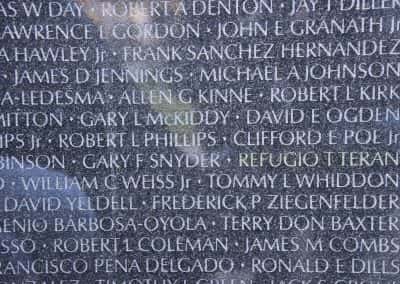

Shortly after graduating from Boy’s Tech High School on the South Side of Milwaukee, Banda joined the Army. He enlisted with many buddies from the neighborhood who he grew up with, including Joe Rocha. Other friends were made and lost during his deployment in Vietnam, like Ed Vesser and Refugio Thomas Teran.

During his enlistment with the Army as a Medic in the 2nd Battalion, 501st Infantry, of the 101st Airborne Division, Banda was awarded many distinguished commendations in Vietnam, including the Combat Medic Badge, Silver Star Medal for Gallantry in Action, Bronze Star for Heroism in Ground Combat, Bronze Star for Meritorious Service, Purple Heart for Combat Wounded, the Vietnam Cross for Gallantry with Palm, and many other commendations.

Thirty-two years after he vanished in the jungles of Vietnam, Refugio Thomas Teran returned home in 2002 to a hero’s burial with full military honors in Arlington National Cemetery.

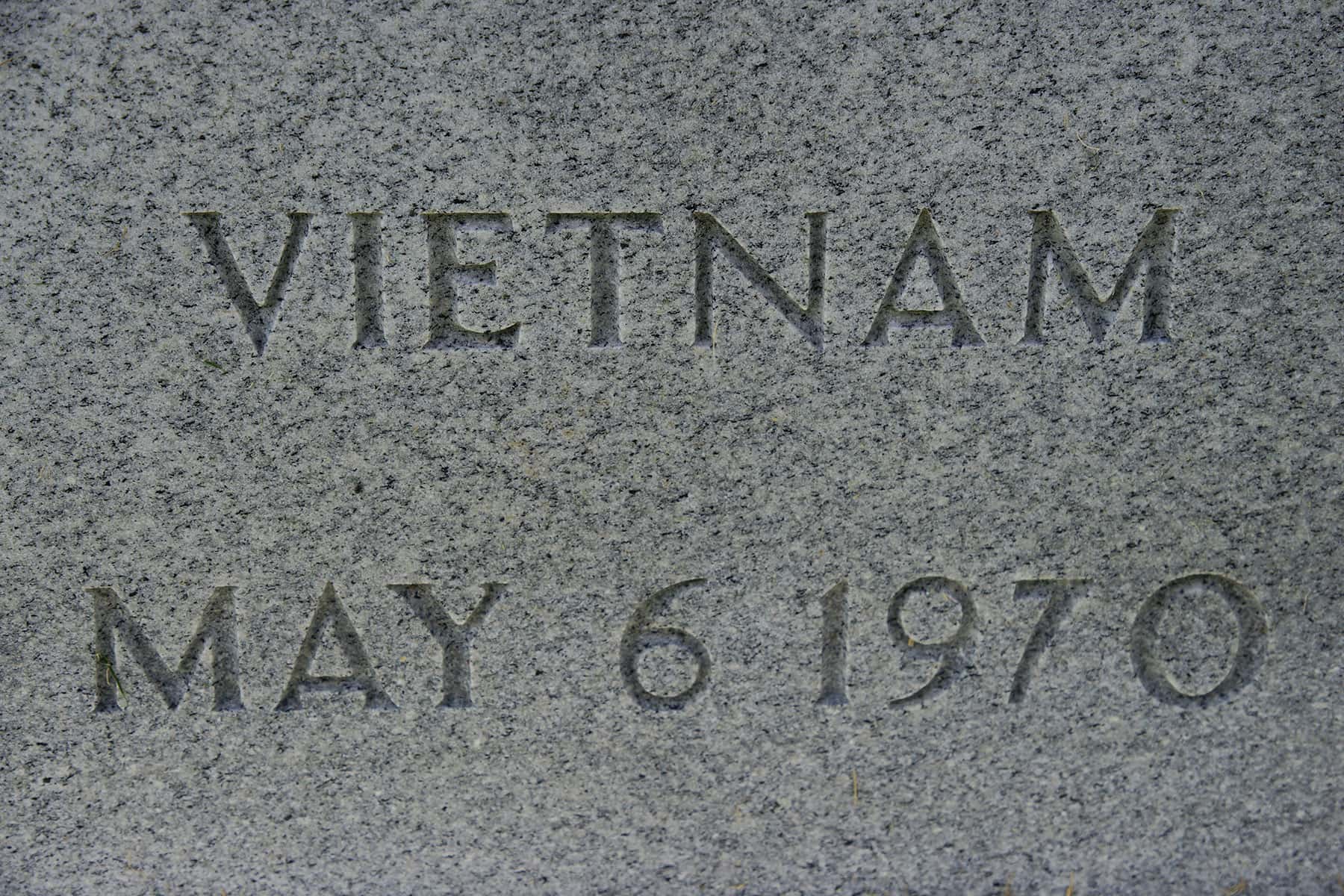

“Tommy” Teran was last seen in the middle of a fierce firefight in the predawn hours of May 6, 1970 as Viet Cong forces overran the munitions dump he was guarding on Henderson Hill, Quang Tri Province. The Americans held the hill, and the next day a search and recovery detail retrieved five injured servicemen and 33 bodies. There was no trace of Private First Class Tom Teran and another rifleman, Larry Kier of Tennessee.

The U.S. government spends millions a year in an effort to retrieve the lost casualties of the Second World War, Korea, Vietnam, the Gulf War and assorted Cold War skirmishes. Since the United States and Vietnam restored diplomatic ties in 1992, the Defense Department has deployed 69 search teams to Southeast Asia, excavating crash sites and battlefields, interviewing aging civilians and soldiers, tracking rumors of unreturned prisoners of war.

A villager scavenging in the area around Henderson Hill Fire Support Base had found Teran’s body later in 1970 and buried it under a simple marker. Searchers from the military’s Joint Task Force eventually recovered and identified both Teran and Kier.

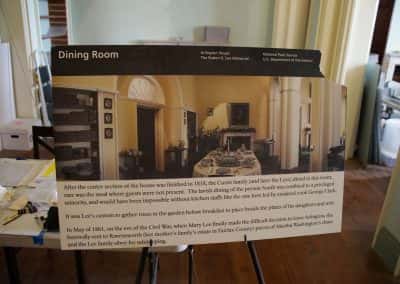

Standing on the steps of Arlington House in Virginia, the Washington Monument and the Nation’s Capital can be seen with the naked eye. Both structures, and many other offices of government would have been clearly visible to General Robert E. Lee when led an insurrection against the country he had given an oath to serve and protect. So it is only fitting that the estate of a national traitor became the home and most hallowed ground of the country’s war dead.

On May 24, 1861, just a few hours after the Commonwealth of Virginia ratified an ordinance of secession and joining the Confederate States of America, more than 3,500 U.S. Army soldiers streamed across the Potomac River into northern Virginia and captured Arlington estate.

Although many believed the occupation of the estate was an intentional insult towards the Lee family, in reality the confiscation of the property was a military necessity. Arlington House was located on the high ground overlooking Washington DC, and posed a tempting target for Confederate forces. Artillery of that day position at the elevation could easily range every federal building in the city, including the White House and Capitol.

Throughout the war, federal troops used the land as a camp and headquarters with forts constructed and incorporated into the defenses of Washington, DC, including Fort Whipple (now Fort Myer) and Fort McPherson (now Section 11). It was not until 1864, when the increasing number of battle fatalities was outpacing the burial capacity of Washington DC cemeteries that 200 acres of Arlington plantation were set aside as a cemetery.

Brigadier General Montgomery C. Meigs, Quartermaster General of the U.S. Army, appropriated the grounds June 15, 1864, for use as a military cemetery. His intention was to render the house uninhabitable should the Lee family ever attempt to return.

Throughout the war, Arlington estate also provided assistance to the thousands of African-Americans fleeing enslavement in the South. On December 4, 1863, the federal government dedicated a planned community for freed slaves on the southern portion of the property, which was named Freedman’s Village. The federal government granted land to more than 1,100 freed slaves, where they farmed and lived until the turn of the 20th century.

Arlington House and its grounds are administered by the National Park Service.

- Lynn Novick: A discussion about her Vietnam War film on Veterans Day

- The irony of visiting heroes at Arlington, the former home of a national traitor

- Photo Essay: Seeing the Nation’s Capital with Milwaukee Eyes

- George Banda: Honoring lost friends in vigil to Vietnam veterans at The Wall

- Maya Lin: Ceremony marks 35th anniversary of Vietnam Memorial’s healing power