Ben Wikler spent so much time poring over polls ahead of the midterm elections that it eventually became too much to bear.

“I was throwing up with anxiety,” said Wikler, the chair of Wisconsin’s Democratic party.

It was not merely out of concern, common to Democrats nationwide in the run-up to the early November vote, that voters were set to give their candidates the traditional drubbing of the party in power, powered by Joe Biden’s unpopularity or the wobbly state of the economy.

Rather, Wikler feared that in Wisconsin his party was on the brink of something worse: permanent minority status in a state that is crucial to any presidential candidate’s path to the White House.

Had Democrat Tony Evers lost re-election as governor, or had the GOP achieved supermajority control of both houses of Wisconsin’s legislature, Republicans could have exercised total control over the swing state’s levers of power – and ensured that its electoral college votes never again helped Biden or any other Democrat win the White House.

“It’s a state where Republicans have tried to engineer things to make it voter-proof,” said Wikler. “All of that meant that, this election cycle, the stakes were explosively high.”

Wisconsin has the most gerrymandered legislative map in the country, designed to ensure the GOP has as easy a path as possible to capture majorities in the legislature, according to a University of Wisconsin-Madison study.

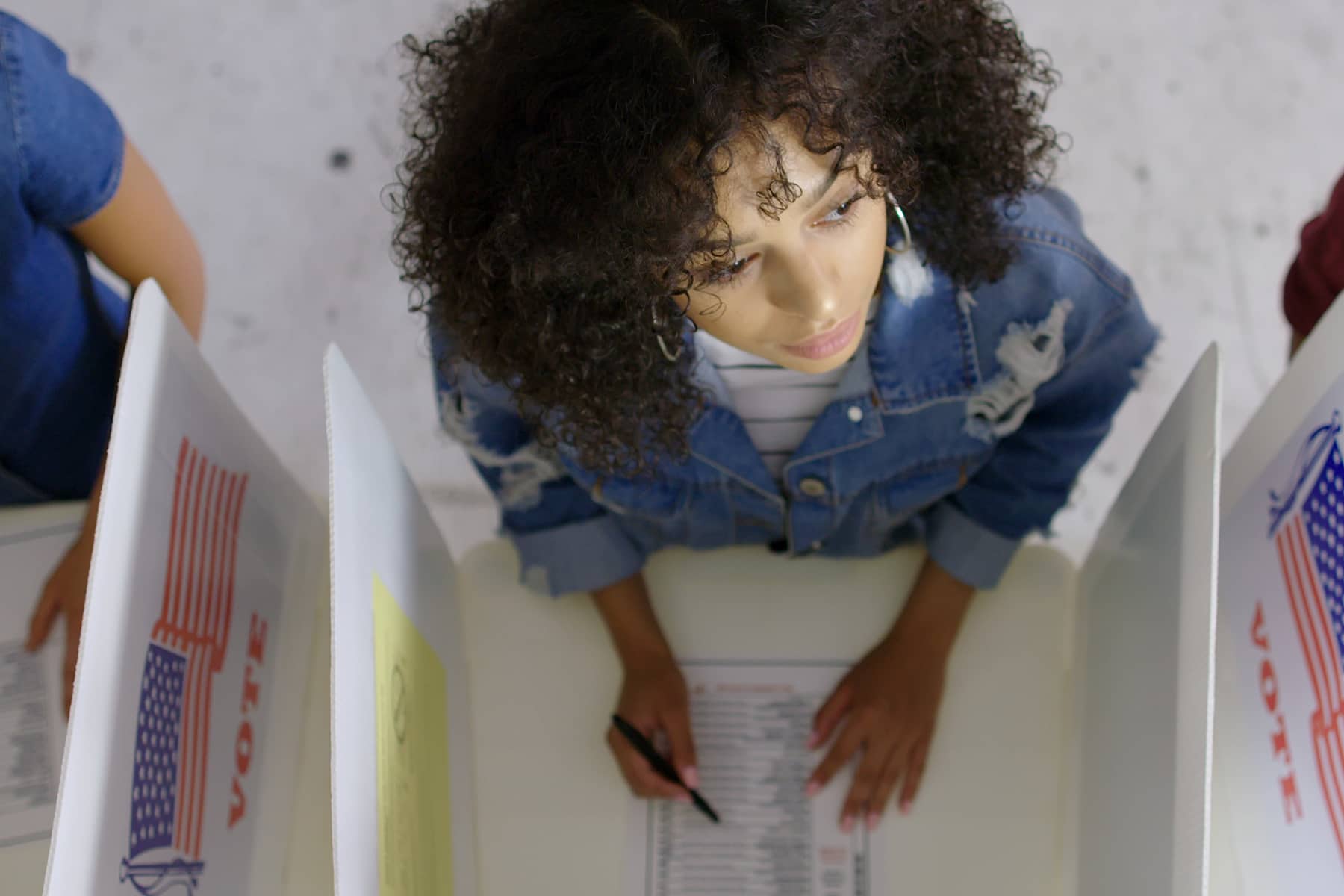

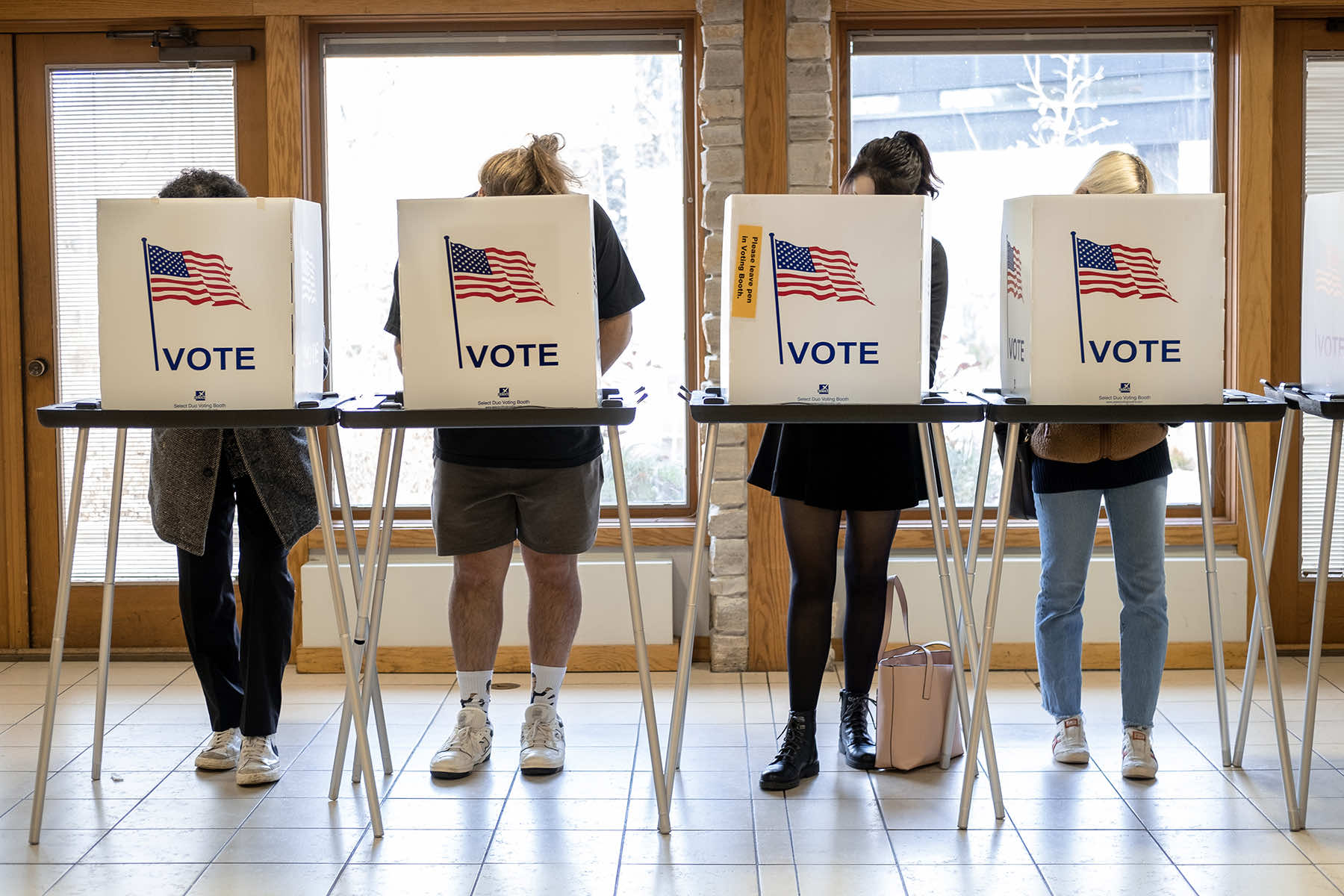

Meanwhile, the Cost of Voting Index ranks Wisconsin as the fourth most difficult state in the country for people to exercise their right to cast a ballot, thanks to its strict voter identification requirements and laws that make it practically impossible to conduct voter registration drives.

But Wisconsin’s Republicans are looking to tighten access to polling places further, and passed a host of measures to do so, all of which fell to Governor Evers’s veto pen. With a supermajority in the legislature, they would have been able to override his vetoes. In a speech to supporters, Tim Michels, the Republican candidate for governor, made it plain that if he was elected, the GOP “will never lose another election” in the state.

“When the state has election after election that comes down to tiny margins, even a relatively small shift in the rules can have an enormous impact on statewide races and presidential races,” Wikler said.

“In that context, if Republicans got unified control of the state government or got supermajorities in the state legislature, it is very easy to imagine a scenario where they essentially rig things to shut out President Biden’s re-election.”

Yet, it did not happen. As the predicted midterms “red wave” collapsed, Governor Evers won re-election, while Wisconsin Democrats narrowly managed to keep Republicans from a supermajority in both houses of the legislature.

“Because of all that, democracy is going to survive in our state,” Wikler said.

Democrats’ success at standing their ground in Wisconsin was one of many pleasant surprises the party experienced in the midterms.

Biden’s allies performed historically well nationwide, but in Wisconsin, Wikler cast their success as something of a turning point: not only will the state remain competitive in the 2024 presidential election, Democrats can now go on the offensive.

“It’s not just that we stopped a total disaster scenario, it’s also that we’ve opened the door to the possibility of dramatic change for the better. And that is almost more than we could have hoped for,” Wikler said.

But the party has a complicated path back to being competitive statewide, and much of the reason why can be traced to another midterm election held 12 years ago.

In 2010, Republicans won control of the governor’s mansion, the state senate and the assembly. They have held the legislature ever since, enacting district maps that have been credited with controversially allowing them to maintain control of the statehouse even if they lose the popular vote, as well as laws that tightened voter ID requirements and curbed the power of public sector unions, a major Democratic voting bloc. The low point for the party came in the 2016 presidential election, when Donald Trump won Wisconsin, the first Republican to do so since 1984.

A year after Wikler took over as the state’s Democratic chair, Biden won Wisconsin in the 2020 election. However, the party’s rebound hasn’t been without setbacks: in the most recent midterms, the Democratic lieutenant governor, Mandela Barnes, failed in his bid to unseat the Republican senator Ron Johnson.

Nonetheless, Wikler now sees an opportunity for the party to undo the state’s gerrymandered maps, and take back control of the legislature, starting with an election for the state supreme court in April. A Republican-backed judge is stepping down from the non-partisan bench, and if a left-leaning justice can replace her, Wikler says the stage could be set for a successful challenge to the state’s legislative maps and a return by Democrats to the majority in the state assembly and senate.

“That’s the north star of the party,” Wikler said. “It’s to have a Democratic governor … a non-Republican majority on the state supreme court, Democratic majorities in the state assembly and state senate, and pass the agenda that Wisconsinites have been yearning for for the last decade into law in one legislative session.”

Chrіs Stеіn

Jim Vondruska and VesperStock

Originally published on The Guardian as ‘I was throwing up with anxiety’: how Democrats fought back in America’s most gerrymandered state

Help deliver the independent journalism that the world needs, make a contribution of support to The Guardian.