This special series by Reggie Jackson explores his journey across four cities in Alabama, to visit historical sites that many are trying to erase from public memory so the disturbing truth about racism, segregation, and White Supremacy can be forgotten. mkeind.com/alabamajourney

We continued our journey down Highway 80 over 50 miles to Montgomery from Selma, following in the footsteps of those who marched against voting restrictions in the South. This part of the journey culminated in seeing two places that I had anxiously wanted to see for many years.

Several years ago when I met attorney Bryan Stevenson, I was enthralled by his mere presence. I had read his book, Just Mercy, and could not wait to see him in person. He was tall and had a gentle voice and a way of expressing himself that made you understand how thoughtful he was. Stevenson has dedicated his life to helping change our criminal justice system. He became intimately aware of the injustices of the system while working in Alabama.

Stevenson founded the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI) to continue his work as an attorney working with death row inmates and others imprisoned in Alabama. According to the EJI website:

“Mr. Stevenson has argued and won multiple cases at the United States Supreme Court, including a 2019 ruling protecting condemned prisoners who suffer from dementia and a landmark 2012 ruling that banned mandatory life-imprisonment-without-parole sentences for all children 17 or younger. Mr. Stevenson and his staff have won reversals, relief, or release from prison for over 135 wrongly condemned prisoners on death row and won relief for hundreds of others wrongly convicted or unfairly sentenced.”

When I met him years ago, he was secretly planning to build a memorial to the thousands of Southern lynching victims, and a museum to tell the story of America’s journey from slavery to mass incarceration.

I missed the 2018 grand opening of the two back facilities. Two close friends of mine, Brad Pruitt and Dr. Fran Kaplan, both attended. They came back with glowing reviews and told me that the late Congressman, John Lewis, survivor of Bloody Sunday, spoke about my mentor Dr. James Cameron and the lynching he survived on August 7, 1930. His story was part of the inspiration for Stevenson creating the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, known by many as the lynching memorial.

His work, and the exceptional scholarship of his colleagues at the EJI have been on my radar for quite some time. In 2017 I attended the “Transforming Public History from Charleston to the Atlantic World” conference at the College of Charleston in South Carolina. Dr. Kaplan and I did a workshop about our work with America’s Black Holocaust Museum. My wife came along for that important trip also.

I attended a workshop during the conference by EJI. I heard about their plans in Montgomery and could not wait to go there. While in Charleston, we visited Mother Emmanuel Church, where nine Black parishioners were brutally murdered by self confessed white supremacist Dylann Roof. We were in the sanctuary where the murders took place, on the second anniversary of the sadistic murders. There was a touching tribute to those who lost their lives that day.

Violence, or should I say anti-black violence, was a theme in many of the places we visited on our trip. It is important to me that we not forget how we have been marginalized, oftentimes treated worse than animals, and murdered with no justice forthcoming in this country.

Today, seeing how easily people want to ignore our plight, and pretend that these things never happened to Black people, is part of what motivates me to travel to the scene of the crimes. As I’ve said many times before, those who used racial hatred and greed as their motivation to treat us inhumanely, left a trail of blood behind.

Montgomery and the Legacy Museum and National Memorial for Peace and Justice, provide places to explore this trail of blood and the copious evidence of these inhumane acts. It is not a journey one can take without an emotional reaction. It is not a journey one can take and not be changed forever. It is not a place that can be erased by those uncomfortable Americans who want to either continue whitewashing or simply erase America’s ugly racial history. It is not a journey that will leave you with any doubts about systemic racism. Instead of listening to silly debates about “Critical Race Theory,” I advise Americans to go to Montgomery.

I arrived in Montgomery planning to visit both places Bryan Stevenson and EJI created but had a bonus trip to the Rosa Parks Museum as well. More on that later.

Amazingly small, but exceptionally powerful is how I would describe the Legacy Museum. The theme of the Museum is, From Slavery to Mass Incarceration. When you first arrive inside the museum you see a display that shows just how important Montgomery was in the domestic slave trade. Most of us are never taught about that aspect of slavery. We hear about the slaving ships but not about the trains and boats that transported enslaved Blacks all over the South. Montgomery was a hub of this despicable business. There were literally dozens of places in town where one could go and purchase Black, children, women and men. The EJI website describes the Legacy Museum in this way:

“The 11,000-square-foot museum is built on the site of a former warehouse where enslaved Black people were imprisoned, and is located midway between an historic slave market and the main river dock and train station where tens of thousands of enslaved people were trafficked during the height of the domestic slave trade. Montgomery’s proximity to the fertile Black Belt region, where slave-owners amassed large enslaved populations to work the rich soil, elevated Montgomery’s prominence in domestic trafficking, and by 1860, Montgomery was the capital of the domestic slave trade in Alabama, one of the two largest slave-owning states in America.”

After seeing this exhibit and a map showing all of the places where people were auctioned and sold you walk down a ramp and see several slave pens. These replicas of the prisons enslaved Blacks were held in, show a small cell with bars and a strong lock with holographic representations of enslaved people telling you their stories. There is a mother who has been separated from her children on one end and a cell with her son and daughter on the other end. The most poignant stories are of a young girl separated form her sister and that of a man separated from his mother. The stories are a powerful testimony to what slavery was really like.

As I walked deeper into the museum and saw validation for what I have taught about American history for decades, I felt proud to stand on the right side of telling history. There are way too many people who refuse to believe the collective lived experiences of Black people in this country. Stevenson and his team have pulled back the curtain and exposed the scars.

Walking through the Legacy Museum is both traumatizing and affirming. Seeing the ugliness that so many endured is painful without doubt. It is not easy to see or hear the gruesome details. However, it is necessary to see and hear those important pieces of evidence.

I’m often asked if my work intersects with re-traumatizing Black people. To be perfectly honest it absolutely can do that. The unvarnished truth about American history is capable of causing re-traumatization. The old saying that the “devil is in the details” is true on multiple levels. This re-traumatizing takes place because we have been separated from the truth and the ugly, intimate details for so long that it comes as a shock to the system.

I have no desire to cause trauma, but I also have no desire to be dishonest about this history. American society is responsible for the trauma that was done to those of us of African descent. Equally, American society is responsible for keeping this truth away from us by refusing to acknowledge it in our schools and society at large. Leaving it out is a form of trauma by not acknowledging our truth.

This dual traumatization does not have to be the norm. The past is what it is. We can’t go back and fix it. However, we can be honest about it. We can demand that our schools are honest about it. We can fight to make sure this history is not buried someplace that we can’t access it easily. We can ensure it’s not hidden anymore, if we have the courage and wherewithal to do so.

My mentor, Dr. James Cameron, as far as I know was the first person to create a museum dedicated to learning this ugly part of the history of Black people when he created America’s Black Holocaust Museum in 1988. His visionary focus on how we perceive our history has helped lead to Bryan Stevenson doing likewise in Montgomery. Cameron was 74 when he first opened his museum, Stevenson was 59 when he opened his.

I could give significantly more details of the inside of the Legacy Museum, but I want everyone who has read this article and not been there to put it on their bucket list. Go there and learn. Come back and teach.

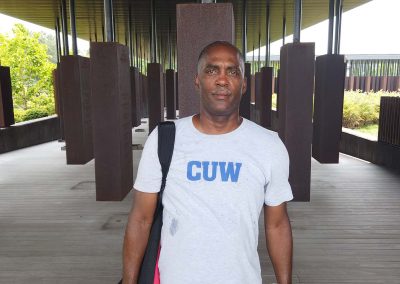

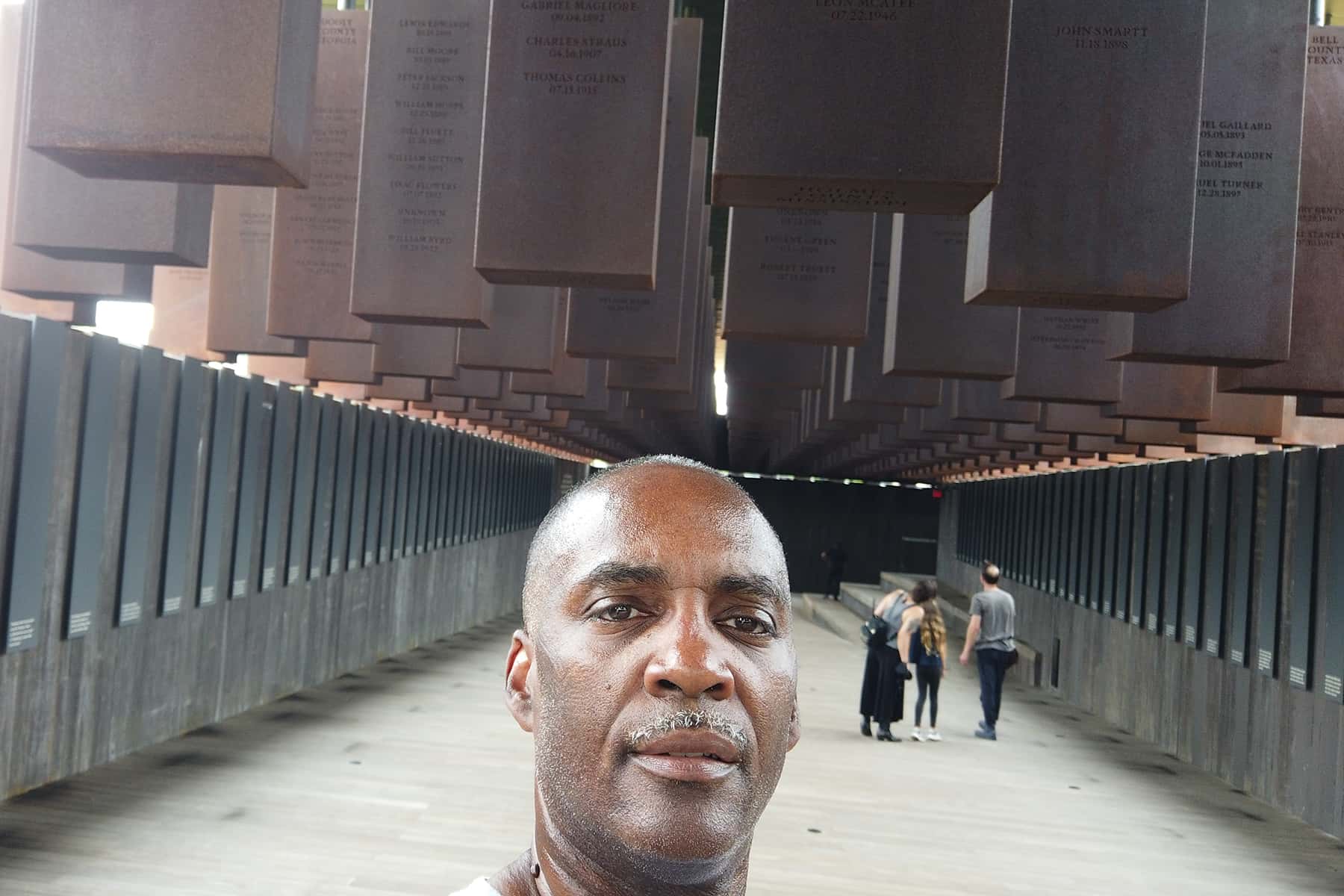

On this hot, muggy afternoon in Montgomery my wife and I next made our way to the National Memorial for Peace and Justice. This metaphorical graveyard for lynching victims is visually stunning and touches your heart and mind. I still think this place, in this location, Montgomery the heart of the Confederacy, is a miracle. Bryan Stevenson is a miracle worker. He was able to secretively envision, design and raise funds for a memorial to lynching victims in a state where 360 lynchings were recorded. Twelve of them were in Montgomery, County.

As you approach the memorial one of the things you notice is that is seems like it’s hidden away. It is designed in such a way that it honors these thousands of victims by showing respect for them by not being a spectacle. It is classy, poignant and dignified.

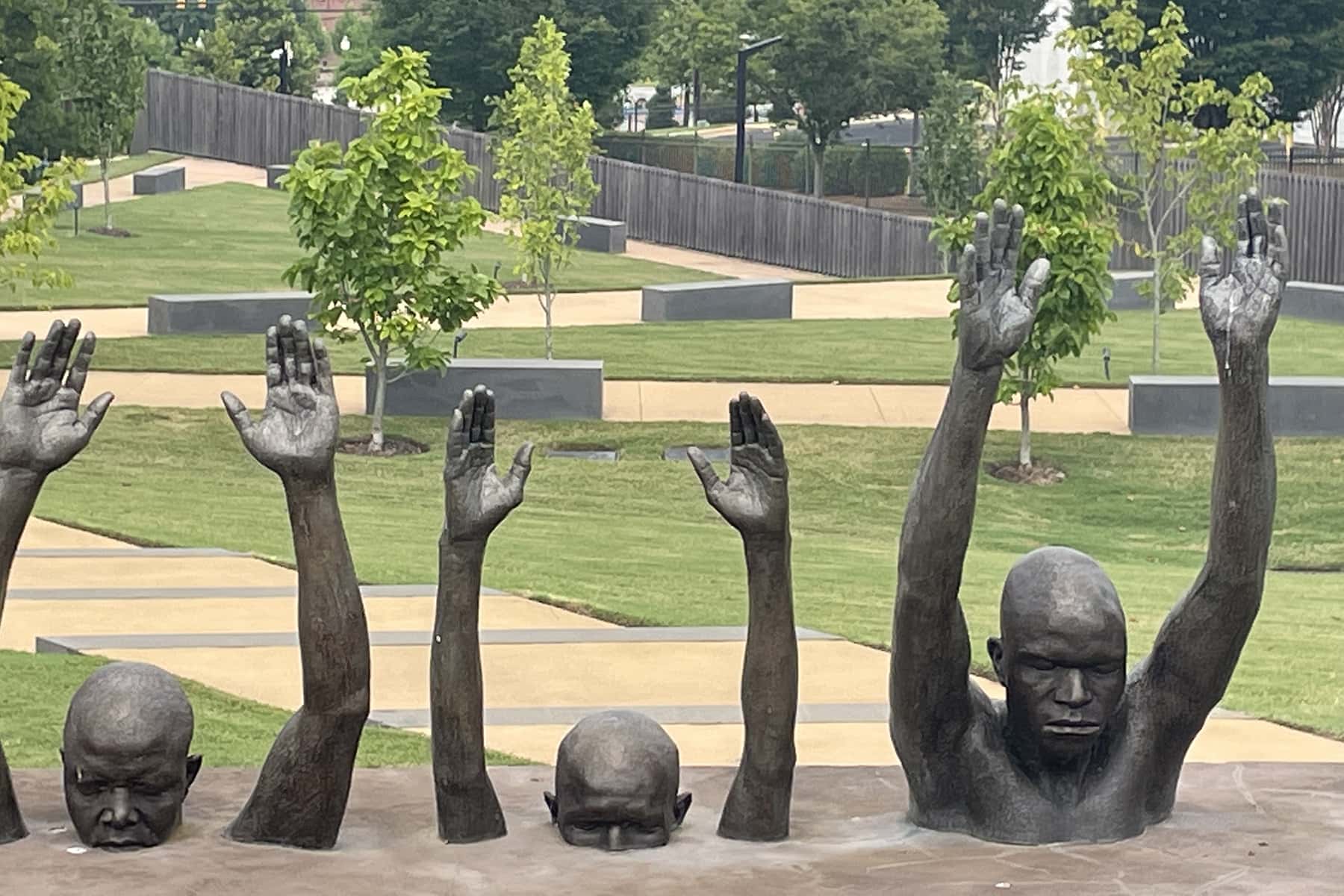

I was struck by how massive it was at the end of the journey, but had no way of knowing how massive it was at the beginning. The first thing that really stood out to me were these life-size sculptures of enslaved Africans in their chains, with looks of fear on their faces.

These seven individuals, three women, three men and a child, confront you as if to say, “this is proof of our existence. We are your evidence of the horrors that awaited us in America and would continue years after official slavery ends.”

The first of these is a proud African man with shackles around his wrists, ankles and chains connecting to a collar around his neck. The look on his face is one of defiance. His facial expression says that “you will not dehumanize me.” He stands tall and proud in his defiance. His right hand is balled up into a fist and his left hand appears to have a broken pinky finger.

There is a woman holding her child next to him, reaching out to the man with her right hand while holding the crying baby in her left arm. She appears to be crying out for someone who is getting away from her. It is symbolic of the separation of our African ancestors, wives and children stolen away from their husbands and fathers.

The expressions on the faces of the mother and child show the pain. You can feel and inside your soul, hear their pleas for mercy. These seven symbolic human beings represent to me those don’t know what horrible futures await them in America. The Memorial shows us all that slavery was just the beginning of this holocaust.

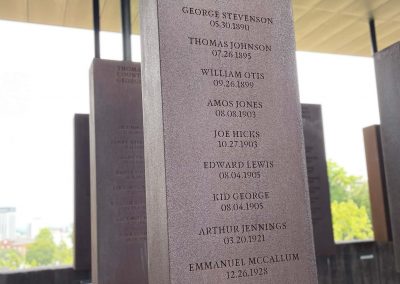

Over 4,000 Black people were victims of American lynch mobs. As you walk up the ramp, you begin to see some of the 800 large steel monuments representing each county where a lynching took place. The names of the victims, and the name of the county where they were murdered are engraved on the monuments.

As I walked passed the first set of monuments, I was surprised at how big they were. The rust that has accumulated on them harkens back to an age when these lynchings were commonplace across the country, particularly in the South. It is literally impossible to understand the scope and immensity of this memorial without seeing it with you own eyes.

I look at the monuments, which are right at face level as you first walk into the memorial, they gradually seem to grow higher as you descend into the depths of hell that was the horror of the lynchings locations.

I immediately noticed monuments from Mississippi counties because that is where I was born. One of these was from Copiah County, located in the center of the state, just south of the state capitol in Jackson. The monument had the names of ten different men, lynched from 1879-1929.

A little further down you see Forrest County, Mississippi the home of Hattiesburg, on the western edge of De Soto National Forrest. The 1830 Indian Removal Act, forcibly displaced the Choctaw and Chickasaw people who called this place home for generations, to make room for White settlers and the enslaved Blacks they dragged along with them. Nine names are on this monument, the first of which is ironically, a man named Stevenson.

I know that among the 800 monuments was Grant County, Indiana where my mentor and friend James Cameron survived a brutal spectacle lynching on August 7, 1930. The crowd of 10,000-15,000 mob members are forever remembered in a photograph shot by Lawrence Beitler. The image of the corpses of Abram Smith and Thomas Shipp in the background, with dozens of smiling Whites in the foreground, is indelibly linked to the institution of lynching. It is the most iconic American lynching image but is mostly mischaracterized as a southern lynching despite the fact that it occurred in north-central Indiana.

I was there to see this particular monument because my mentor survived that lynching. Had he not survived and told his story, and founded the museum, I doubt that this memorial in Montgomery would exist. The power of that image and the story of the survivor are a unique part of the history of lynching in this country. Millions have been to this memorial over the years, and I doubt if more than a small few know that story and connection with James Cameron, his museum and the sonf Strange Fruit, written by Abel Meeropol who saw the image several years later.

After sweating, through the hot weather at the memorial, taking dozens of pictures, I began to notice little placards telling the story of why some of the victims were lynched. I’d like to share a few.

“Three brothers with he surname Slyvester were lynched in Proctor, West Virginia, in 1886 after they were accused of theft.”

“Sampson Harris was lynched in Bienvielle Parish, Louisiana, in 1885 after threatening to report white men for whipping his neighbors.”

“Caleb Gladly was lynched in Bowling Green, Kentucky, in 1894 for walking behind the wife of his white employer.”

“Private James Neely was lynched in Hampton, Georgia, in 1898 for complaining when a white storeowner refused to serve him.”

“After an overcoat went missing from a hotel in Tifton, Georgia, in 1900, two black men were lynched, whipped to death while being ‘interrogated” in the woods.”

The myth of lynchings being due to sexual crimes by Black men is exposed in this place. Ida B. Wells over 100 years ago had already told the world that that story was a lie. In her 1909 report, Lynching, Our National Crime she wrote this:

“The lynching record for a quarter of a century merits the thoughtful study of the American people. It presents three salient facts: First, lynching is color-line murder. Second, crimes against women is the excuse, not the cause. Third, it is a national crime and requires a national remedy. Proof that lynching follows the color line is to be found in the statistics which have been kept for the past twenty-five years.”

The Memorial for Peace and Justice, likewise, is an attempt to set the record straight. It does so in a majestic memorial that has to be experienced to understand well.

My most lasting memory was seeing the second set of the monuments, that are stacked side-by-side near the end of the journey. I found Grant County, Indiana. There I looked down at the names and saw the engraving that said:

Grant

County

Indiana

Abraham Smith

08.07.1930

Thomas Shipp

08.07.1930

I paused at this place to pay homage to Dr. James Cameron and his two friends Abe and Tommy. It was an emotional moment for me and the central reason I wanted to make the trip. I had 18 years ago travelled to Marion, Indiana and visited the small, nearly hidden, cemetery where Abe and Tommy were buried in unmarked graves in 1930 to protect their remains. This was full circle for me. I had seen the site of the murder that led to the lynchings, visited the inside of the jail they were snatched from, visited their final resting place in a corn field in the middle of nowhere, and now seen their memorialization in Montgomery.

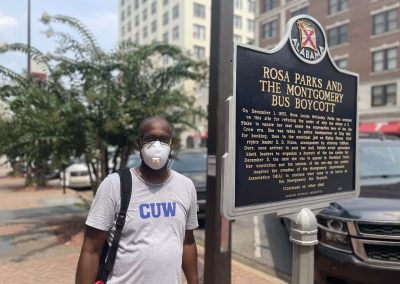

After we left the memorial we had about an hour before we could check in to the hotel. We quickly drove to the Rosa Parks Museum with about an hour left to see it before closing time. We stood on the spot where Rosa Parks was arrested in 1955 and had a nice woman take a picture of the two of us. I noticed out of the corner of my eye that a man and his daughter that we had met in Birmingham were walking up to the Rosa Parks Museum. It was one of those moments that makes you realize how small the world is.

The museum featured a bus with a window showing a visual representation of the events that day. It was interesting to see the actors playing out that day’s events. I would certainly recommend those that want to see the truth of Rosa Parks and her importance to the Civil Rights Movement come to this museum.

As we left Montgomery on our way to Atlanta to visit my cousin, I knew we would pass by the city of Tuskegee but was not sure we had time to stop there. My wife convinced me we should. I’m glad she did. I will discus that part of the trip in tomorrow’s column.

- Reggie Jackson: My journey to visit Birmingham, Alabama and the history some want us all to forget

- Reggie Jackson: My journey to visit Selma, Alabama and the history some want us all to forget

- Reggie Jackson: My journey to visit Montgomery, Alabama and the history some want us all to forget

- Reggie Jackson: My journey to visit Tuskegee, Alabama and the history some want us all to forget

- Reggie Jackson: Final thoughts on my journey to visit Alabama and the history some want us all to forget