Writing my final column of 2018 was a collaborative effort, a fitting endeavor in a world wounded by so much divisiveness. It is both a Künstlerroman about an artist’s growth, a story about the art itself and, in essence, a story of Milwaukee. The artist, Stefanie M. Valverde, has represented the complicated history of Milwaukee in a 4’x6’ oil painting, using extensive research, digital sublayers and knife strokes thick with oil paint to discover what she calls “The [Real] Heart of Milwaukee.” Her first-person narrative is a combination of her own written words and an in-person interview I conducted following the benefit auction for ZIP MKE at which her painting first appeared. It was truly a pleasure to work with her and understand her process as an artist, her personal journey from Venezuela to Milwaukee and her hopes that her artwork will inspire more dialogue in our city about our past, our present and our future.

DISCOVERING MYSELF

Two years ago, I was researching ideas for a tattoo. I remember coming across the vibrant long-tailed sylph, which is supposedly the only bird that has ever migrated from its native mountains in Colombia, Ecuador and Venezuela all the way to Wisconsin. At the time, I didn’t question why it would migrate north to a cold place like ours. Instead, I was amazed learning that they travel the same route that I myself took to get here: my mother was born in Barranquilla, Colombia, and my father in Loja, Ecuador. I was born in Caracas, Venezuela, and I moved to Milwaukee a little over three years ago.

So now a tattoo of the hummingbird adorns my left forearm, a testament to my own sylph-like journey. Recently, however, upon searching again for the information about the migration, I couldn’t, to my surprise, find anything online anymore. I’m currently waiting to hear back from the Urban Ecology Center in hopes that they can help me re-find or research this information. If this avian journey remains a curious mystery, I will embrace it as an intriguing and magical parallel with my life.

Venezuela was and still is a civil war zone. I remember the time when my mom held a white rag over my face as we got onto a bus. I didn’t know why, but I soon realized that the military was launching tear gas and it was reaching the people around the supermarket we were at. This was one event that catalyzed my constant back-and-forth migration between Venezuela, Colombia and Ecuador for the first six years of my life. I was raised, then, in Miami, Florida.

In Miami, so many of my classes kept leading me to art and social justice. History courses allowed me to learn about the United Nations, which spurred my self-promise to work there one day. Mathematics allowed me to see the connection between numbers, philosophy, and art. I learned about Pythagoras, Plato, and Aristotle, all people who understood and researched and expanded on the importance and relativity of math and life. Science courses amazed me as my teachers taught us about innovators and the universe – about quantum physics. Not surprisingly, the humanities unified the arts for me – literature, music, dance, visual arts. I understood, or was beginning the journey of understanding, how resolutions to problems arise so beautifully when fields operate collaboratively and how powerful they become when they are rooted in fields that acknowledge each other.

My classes kept leading me to art as the answer to helping not only my native country, but, my adopted one too–because art was the field in which I saw the greatest openness and acceptance. I saw a desire, or even requirement sometimes, to collaborate with other spheres of knowledge. I believe that we need the influence of art, the welcoming of languages and the acceptance of cultures to truly function at our highest potential. Growing up exposed to the oppression in Venezuela, and then learning about it even more through research (the government in Venezuela limits the leakage of news outside the country) while attending school in the U.S., helped cement my drive to help, both here and there. I felt in my soul that I had to. I saw myself speaking to hundreds and thousands of people about political awareness and the strength to change our lives.

It also makes sense that I ended up picking the art field because of my dad, who was involved in the visual arts field, too. He studied dibujo lineal, or technical drawing; drawings of architecture; portraiture; glass work. He also studied abstract and surrealist and contemporary art. I recently learned that he loved making portraits in charcoal, landscapes in watercolor and acrylic paintings on canvas with palette knives and brushes. The most special memory I have from his artistic explorations is this: I remember helping him peel off the tape from massive pieces of glasses from his other projects. I never learned the terminology for this process – I was so young – but I remember falling into a trance when the tape followed my fingers and left the surface. What remained were magical, low-relief figures. I still remember their texture. Eventually, he became an architect and was so passionate about it. In fact, he gave his all for his business to expand from Venezuela to Ecuador and, recently, into China.

I started college at 15 years of age through a Dual Enrollment program at Mater Performing Arts Academy Charter High School, that encourages teenagers to attend university classes at different campuses in order to earn a degree before, or by the time, they finish high school. So I graduated high school with an Associates Degree in Arts from Miami-Dade College. I then came up to the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, where I earned a Bachelor of Fine Arts Degree in Digital Studio Practice with a cross-disciplinary in Painting and Drawing and a focus in Art and Social Practice. It was the most diverse, community-involved, independent research major I could have ever had the privilege of pursuing.

I had researched many universities and their cities to determine the best place to pursue the dream I had had since I was fifteen: to work for the United Nations, then start my own organization of artists and creatives to unite people in empathic ways. When I found that Milwaukee was the most segregated city in North America, I decided to apply to one, and only one, university: the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. Though previously I had been applying to scholarship competitions, in the end I turned down all of the ones that required me to attend other universities – even a full-ride to New York University – to immerse myself in this city where there was so much potential to do the work I wanted to do. My mother thought I was nuts at first but eventually supported my decision.

DISCOVERING MILWAUKEE

The first time I moved to Wisconsin, I lived in Hartland for the summer. After summer, I moved into the city to begin school, but one memory sparked the affirmation of this intense gut feeling that I needed to be here. I remember walking from the Harley Davidson Museum across the 6th Street bridge… I remember walking past curious little antique stores, past a remarkable pink building, into an abandoned old building right in front of the pink one (I didn’t know this was illegal), out, and past a gigantic orange building that may have been a factory… or a very old apartment complex with countless windows.

Another antique store sat on a different corner and just past it, a mysterious club, or what seemed to resemble a club, with architectural elements and colors that reminded me of Venezuela stood with gracious and humble conviction. The best part was, that when I continued walking a little more, I encountered numerous houses that formed communities of families walking around and sitting out on the porch. It was night time, so I remember the orange glows gleaming and illuminating from inside, the outer house walls and rooms on upper floors. Though I didn’t mean to stare, I couldn’t take my eyes away from one particular man dressed in a white tank top – he reminded me of my dad – who walked across a kitchen several times. It was like watching a little film. The “screen” only showed that small-framed, two-dimensional area. I saw a black toaster and a white fridge, a small picture by the door frame to the right. And that was it.

But that night I realized that everything on the south side of the bridge was different from the north side. I saw so many people – including the man in the window- that were my color! I understood. The city’s segregation, with quadrants of the same kinds of people, finally made sense. It was more than data and history–I experienced a mixture of beauty and terror: beauty in seeing all the brown faces that reminded me of Venezuela, terror at the realization of why all the brown faces were, predominantly, in the same area.

I came back to this area a year later and cried. I realized, more than ever, that If I couldn’t directly help my native Venezuelans, then I wanted to help those whom I could, at least for the time being. I saw the struggle of culture clashes here, as well as the beautiful, flourishing relationships people made with each other. But remembering conflicts in Venezuela kept me going on this journey to either work for the UN, to help my country and other countries that suffer from miscommunication, or to move forward on the motivating path towards creating my own organization to help people.

News about Venezuela had always felt like a stab in the stomach, as I watched from afar my fellow Venezuelans suffer. However, recently I reconnected with my best friend from infanthood, Pedro. He never left Venezuela. But he reawakened me and re-instilled in me a sense of duty to continue using art and culture in the social and political fields to help people. The historical and even current conflicts between powerful governments and oppressed people in both Venezuela and the U.S. parallel in my eyes. If artists can help citizens think critically, to use the voices they have, and do so with resilience, we can truly challenge the existence of these barriers and get one step closer to freedom.

DISCOVERING THE RIGHT QUESTIONS

This summer, I was invited by the local community organization, ZIP MKE, to participate in a silent auction called “(Re)presented”, for which over thirty artists would choose a photograph from their collection of faces, places, and experiences from all 28 ZIP Codes and re-present them in a new art form. When I read their origin story – their “why” – I realized that everything I stand for aligns effortlessly and irrevocably with its mission:

Milwaukee is experiencing a new wave of energy that seeks to change its narrative: to transform the city into one that is safe, fun, accessible, and prosperous for all its citizens, a common ground of equal opportunity for everyone, from all neighborhoods. ZIP MKE realizes that, on a fundamental level, this will not be possible until the artificial geographic boundaries of ZIP Codes and neighborhoods and cross streets are transcended, and until the psychological barriers that prevent us from uniting to work together are demolished.

Founder Dominic Inouye created ZIP MKE, in part, as a response to the officer-involved shooting of Sylville Smith on August 13, 2016, and the violent unrest that followed, but more so because of the language he heard people using when debating about the events, especially on social media, dichotomous and divisive terms like ‘city/inner city,’ ‘urban/suburban,’ ‘good neighborhood/bad neighborhood,’ ‘the hood,’ ‘the ghetto.’ That neighborhood. Those people. Black people. White people.” He asked himself: What can I do, what can we do, to bridge these gaps that allow us to talk about each other without really knowing each other?

The answer? Change our perspective, then change our perception. If we change what we see, we can transform how we see. The word “perspective” comes from the Latin perspecire, which means “to inspect or look closely at,” and our word “perception” comes from percipere, which means “to seize or understand.” It is only when we see each other and the spaces we inhabit that we can begin to understand each other and seize the possibilities for change.

I create because every time a new project comes up, it seems like every single step and choice I’ve taken in my life was meant for that one work. Like everything I am is because I feel a crucial immediacy to bringing awareness to our cultural dilemmas. Art is a voice, a medium, a tool of communication which has oftentimes been taken for granted throughout history.

I have found that, just as ZIP MKE’s “why statement” declares, “if we change what we see, we can transform how we see.” This mirrors the process of my practice, for I am pulled by spaces, their lines, their negative and positive areas, the shapes they form and their energy. It occurred to me that the spaces I am pulled by are the same spaces that are connected to, unfortunately, divisive and complicated historical timelines for different cultures, neighborhoods and values. The photographs of the places with which I work carry stories with people who endure continuous obstacles that we can help solve.

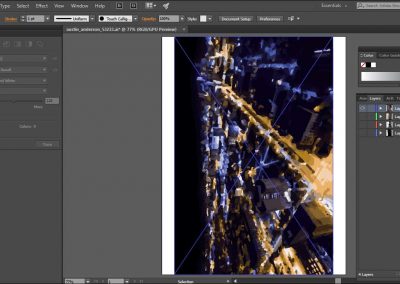

When ZIP MKE gave me the chance to choose one of their photographs to inspire the work I would create, I realized that a pair of Austin Anderson’s drone photographs were the ones. Both were taken from the Marquette University campus, one extraordinarily dynamic in its line and color movements, the other intriguingly empowering in its environmental gradient and inevitably noticeable geometry. They resonated with me – the architecture, the locations and the photographic moments’ auras had a tremendous affectual response in me. I decided to reach out to Austin and get to the bottom of this inexplicable impact. Here is an excerpt:

I knew I belonged here for a while. But I really knew, once I saw the architecture in Milwaukee. It dances a different rhythm from old to new with each structure. Your images remind me of the beauty and the terror that I saw and felt the first time I stepped foot in Milwaukee. I love this city, and I feel I owe it a painting that speaks of a part of its identity through a different angle. But first, I need to know the following: Why use a drone? Why those two different times of day? Why those structures? And, did you notice the relationship between charged and slower spaces in your compositions?

I was ecstatic when he replied, in part:

Since I was a Marquette student and the campus is situated right in the heart of Milwaukee, the extreme contrast between the blue, cool temperature lights and warm tungsten street lights literally make it look as if Marquette’s blue and gold colors are bleeding into the city. It is similar to the work that many of my friends were and still are doing in the city, through a variety of organizations. In my case, it was my contributions to getting ZIP MKE off the ground. In other cases, it’s helping disenfranchised families and students in afterschool programs. In any case, the goodwill and generosity flows from the campus into the surrounding areas that you can quite literally see in the lighting in this photo.

These are some of my earliest aerial photography work, so I really appreciate you working with my photos! In the case of the night photo, that was literally my first finished image I ever produced from the air, so I am really glad that it can be a vessel to help you continue the dialog that ZIP MKE has created in Milwaukee.

We corresponded multiple more times, and each time I learned more about why Anderson used the drone, what inspires him, his observations of the world and so on. Then, after many more hours and days talking with my dearest friend Libby–one of the most brilliant minds and golden hearts I’ve ever known, plus founder of The Bus Art Project MKE–about the reality of this city, I started researching. A lot. Intensely.

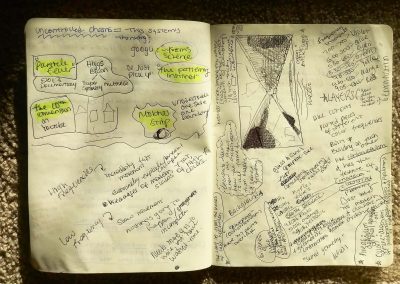

I started looking for words and phrases from my correspondence with Anderson, my schooling, and elsewhere that could help guide me into the question around which this work would be created. I was looking for keywords that would, much later, become the backbones for the elements found in the final painting, “The [Real] Heart of Milwaukee.”

My sketchbook became a massive list, which included:

- Challenging

- Blue and gold are bleeding into the city

- Getting MKE off the ground

- Contributing to it

- Helping disenfranchised families and students

- Good will

- Generosity

And later:

- Digital sub-layer

- Heart of Milwaukee bleed

- Traditional

- (Re)practiced

- Contemporary

- MKE

- Adversities

- Triumphs

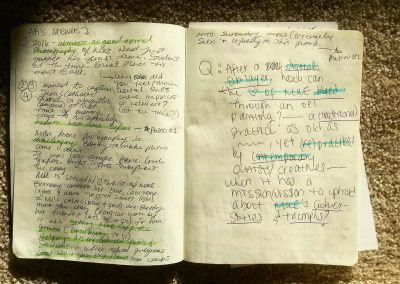

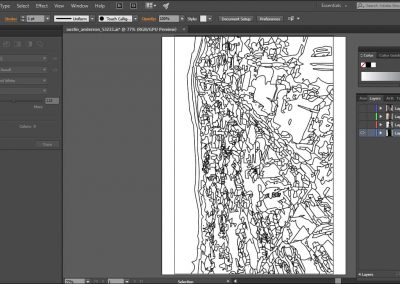

These words, plus a seemingly insurmountable amount of research, led me to this question: “If I created a digital sublayer from Anderson’s photographs, how could the heart of Milwaukee bleed through an oil painting with the mission and vision of upholding both Milwaukee’s adversities and triumphs?” In essence: “What does the real heart of Milwaukee look like?”

DISCOVERING (AND GENERATING) THE LAYERS

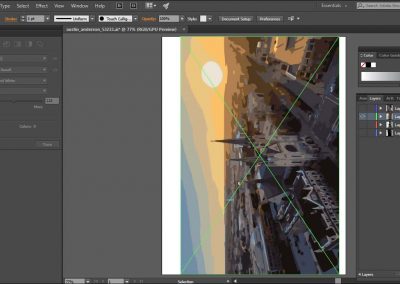

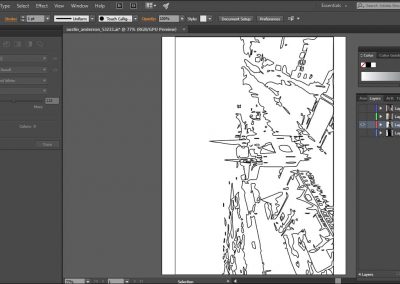

One of the early steps in the process I use to create much of my art is the creation of a digital sublayer, which is a form of “generative art” – a fascination I re-discovered while constructing my thesis in art school. A digital sublayer is like the prior step to a traditional underpainting, the layer that helps manifest the composition. To create a digital sublayer, I insert images into a digital software platform, such as Adobe Illustrator, abstract the image by extracting all the vectors (generatively, through the Trace Image option) and edit the final files into a set of layers that are rotated and alternated in opacities. The final result is the “blueprint” I use for the base of the painting. Though this method is not used for aesthetic purposes, but rather, a form of generative art used to study spaces and their relation to other elements of research such as population, historical time frames and so on, I do find it quite beautiful when the outcome etherealizes into what appear like maps of some sort.

Much like life is a form of generativity, creating a digital sublayer allows an artist to let go and see where the image goes. I stripped Anderson’s two photos down to the core outlines of all the structures, rotated them, superimposed them – and discovered that the result looked like a map. In Milwaukee’s history – in the history of any city – there are lots of rotations, lots of overlaps. And lots of layering. I mean, if you research and read and read more about our city here, you find out Milwaukee carries more than 160 years of people moving in from all over the world. Our contributions create layers of history over time and alongside our industry history, there are a lot of overlaps between different cultures that have made this city what it is today.

Before the 1800s, we had settlers and we had the earliest tribes that were some of the most influential traders. Layer 1. Then underdeveloped areas of Milwaukee (the south side, for instance) remained so for years because of laws that prevented advancement. Layer 2. Then the battle between quadrants grew, and it was the East versus the West side due to war bridges by the river, and then the South got involved once more, until this back-and-forth fight was concluded and people realized they needed to work together to live as one. Layer 3. The quadrants became one city. Layer 4. And then a couple years later, we had our state. Layer 5.

If you were to draw a continuous contour line drawing, based on the history thus far, you would get the same result I saw when I overlapped Austin’s photographs. It’s the same when you abstract and layer any group of images of places together. Maps are lines and quadrants created by negative and positive spaces from boundaries and time. I wanted to bring to life a painting that carried the historical heaviness and congested layers of our history: German immigration, population spurts, increasing diversification yet equally increasing separated ethnic and racial quadrants, the push for industrialization that brought technology and the pretty buildings and structures we see today, but the class and status differences struggles it also brought.

Fast forward to World War I, opposing sentiment from the product of this war, identity explorations and adverisites, our famous beer state’s not so popular beer prohibition, the Great Depression, and, of course, things got better again and the economy rose once more much after World War II. Soldiers and families had the opportunity to live in newly constructed homes. This meant progression, yet, more broken apart communities, and, as divisions between rural and urban housing came into play, racism grew and discrimination grew tenser as even more African Americans immigrated to the city and redlining was enforced. Unjust forces prioritized housing projects and freeways and many people lost their homes.

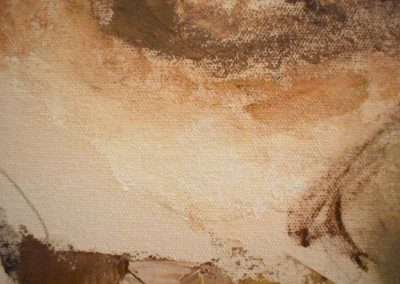

Our city has a lot of history. But just as ZIP MKE recognizes, the painting that emerged was a beautiful opportunity for us to remember that even if our truth has elements that are ugly, it is okay, and in fact, it is all the more reason to acknowledge it. This painting’s color palette represents the old and the new, the classical and the modern, the quadrants of which the city is made. This painting is an unapologetically physical, diverse, yet segregated representation of Milwaukee – emblematic layer after layer after layer of history. This exists through the bleed of the colors and oils, through its congested layers of palette knife applications, through its staining, its rubbing and breaking, additions, subtractions and hidden coatings. Our crossed paths and lines, as well as their intersections, are all there.

THE [REAL] HEART OF MILWAUKEE

I was very honored to have the chance to help participate in the (re)presentation of part of ZIP MKE’s photographic archive of the city of Milwaukee to bring about something real, something that is not sugar-coated or meant to just look pretty. I wanted to create something that would kindle our current discussions, to get us thinking about our communities and why they look, historically, the way they do. Hence the bracketed “[Real].” Yes, it’s real, and it’s complicated, layered and sometimes ugly, but we need to get uncomfortable, embrace its history, and help it progress.

What makes the real heart of Milwaukee, however, is its people. People make actions, people move things, create things. And while our heart is made up of the actions and decisions that manifested unfair laws and that created and sustained segregation, our heart is also made up of the desire to stop these laws. The heart of our city lies in our hands, in our actions, and in our desires to do good.

Stefanie Valverde’s artwork is currently on public display in the lobby of the Reuss Federal Plaza office building at 301 W. Wisconsin Ave. Other artwork inspired by ZIP MKE photographs is also on display and for sale through February 2019. ZIP MKE will host a special Gallery Night event in the space on Friday, January 18, 2019.

© Photo

Dominic Inouye and Stefanie M. Valverde