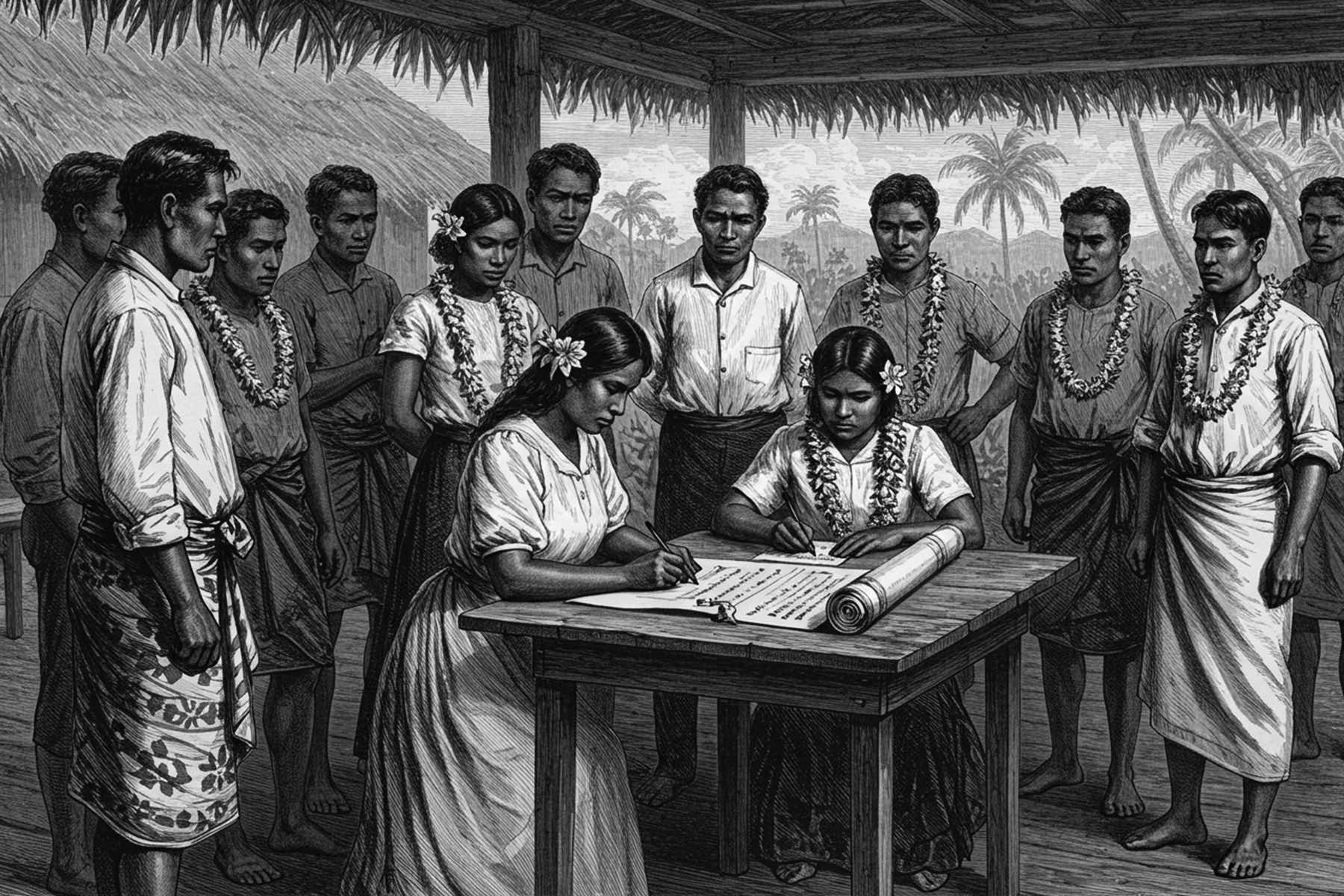

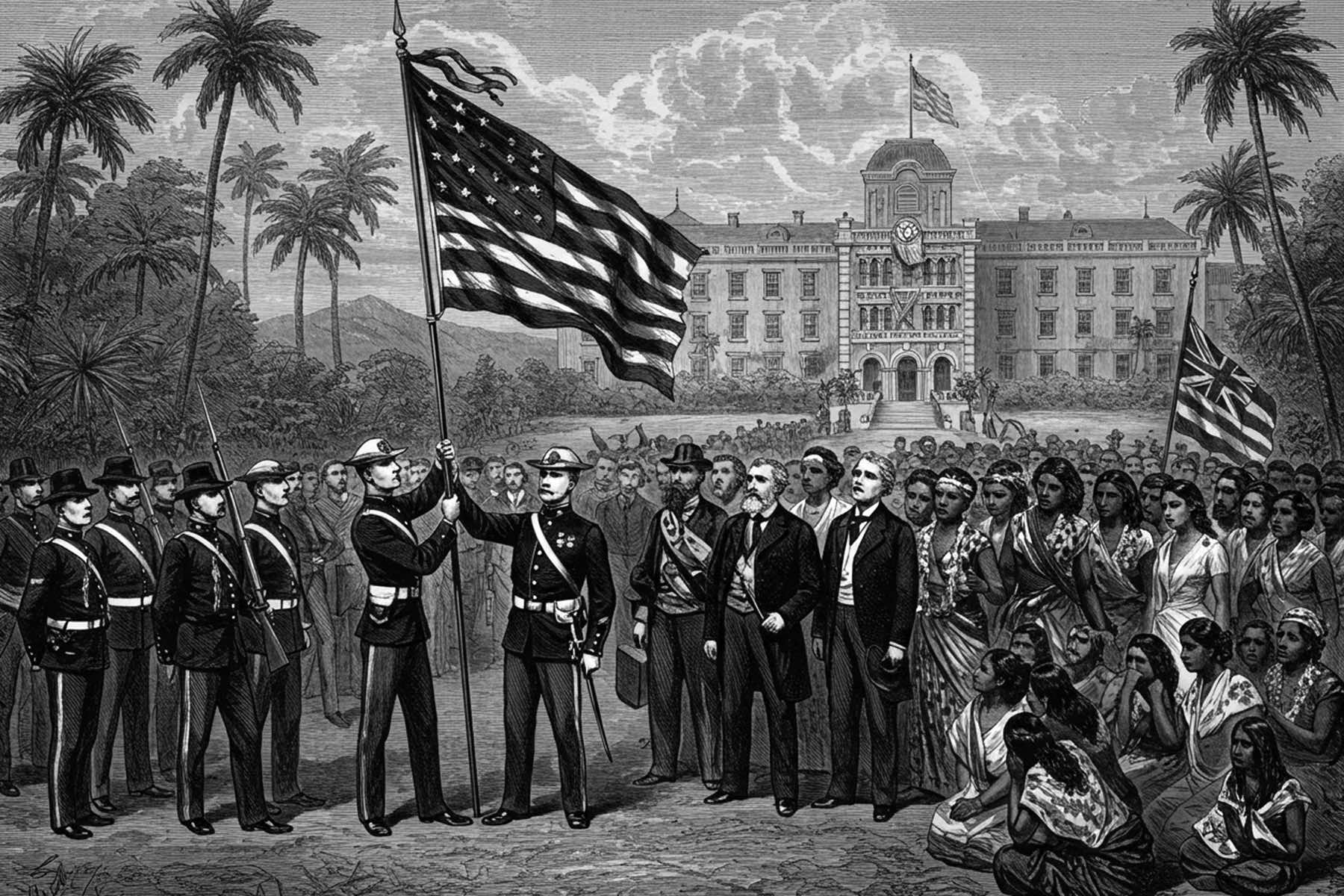

On July 7, 1898, President William McKinley signed the Newlands Resolution, formally annexing the Hawaiian Islands into the United States.

Widely criticized by Native Hawaiians and later condemned by the U.S. government itself in a 1993 congressional apology, the decision marked the end of an independent kingdom and the start of America’s imperial footprint in the Pacific.

While often remembered as a clash between Pacific powers and Washington’s ambition, the road to annexation was not paved by East Coast statesmen alone. A midwestern state thousands of miles from the Pacific played a surprisingly formative role.

Wisconsin exerted its influence through missionaries, businessmen, political advocacy, and moral justification campaigns that reached from pulpits in Madison to sugar plantations in Maui.

AMERICAN EYES ON THE PACIFIC

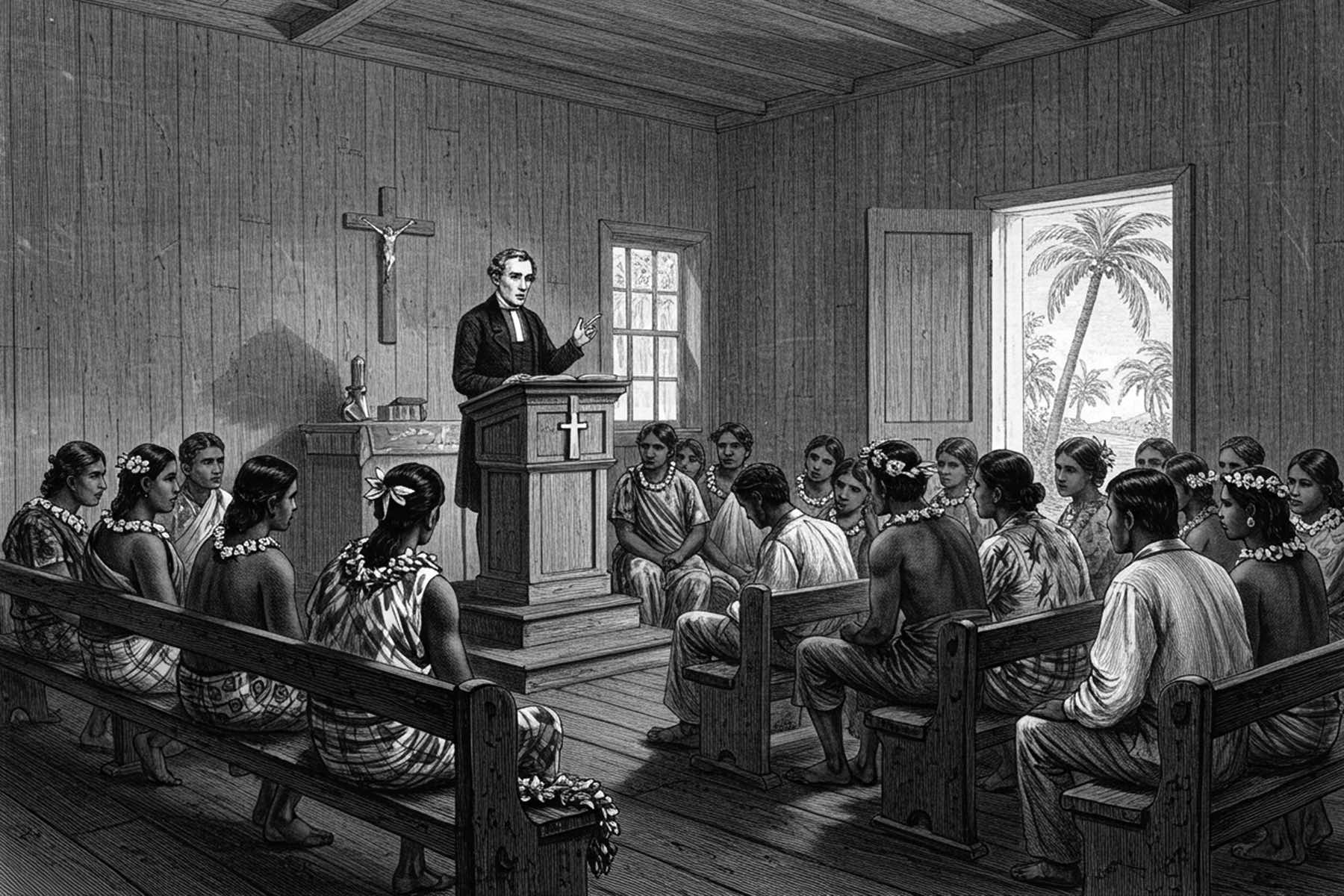

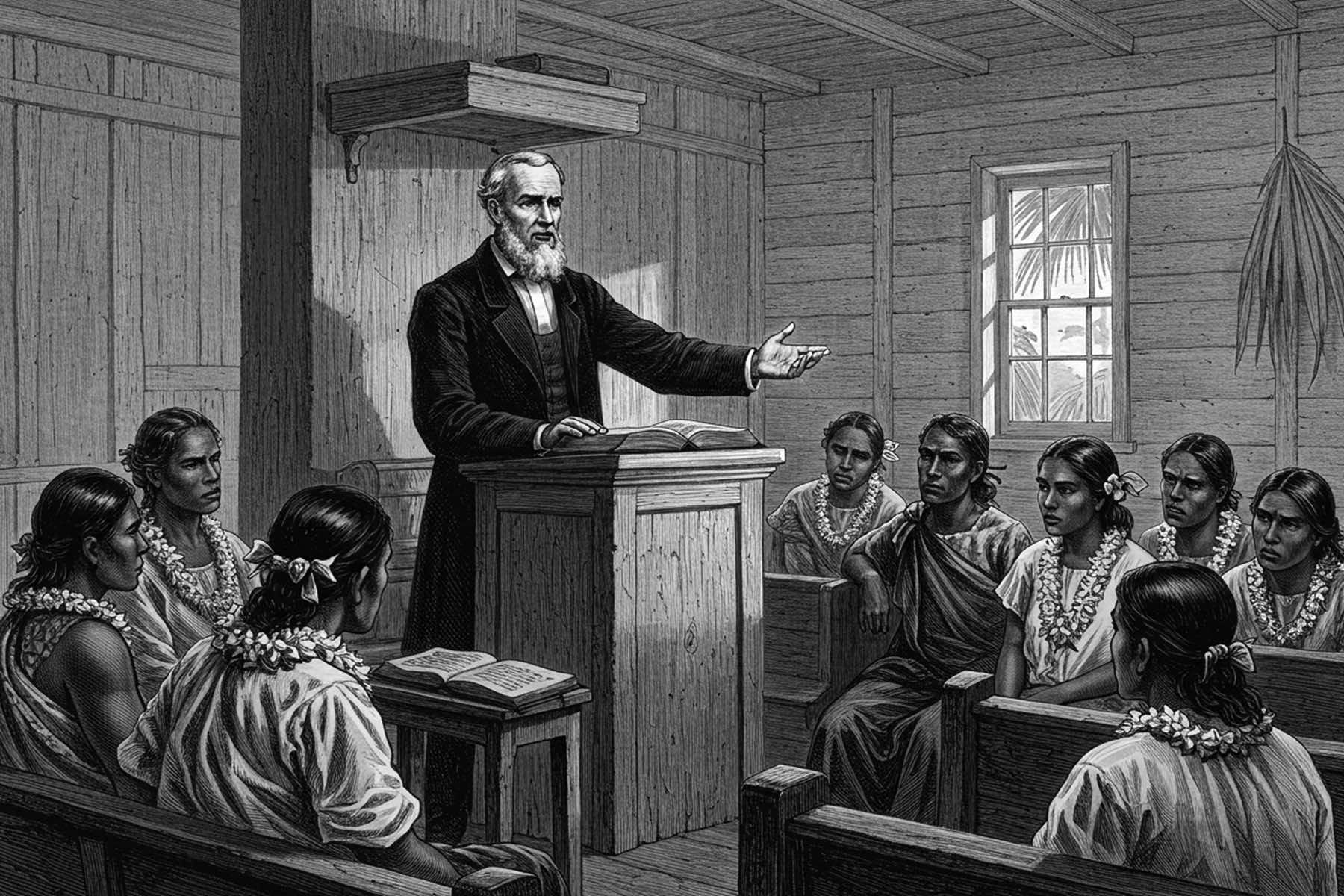

Long before the overthrow of Queen Liliʻuokalani in 1893, American missionaries and merchants had established deep roots in Hawaii. The first wave of Protestant missionaries arrived from New England in 1820, bringing Christianity, Western education, and a restructuring of Hawaiian land and governance.

Their children and grandchildren became plantation owners, bankers, and political figures who reshaped the islands into an economy reliant on U.S. trade.

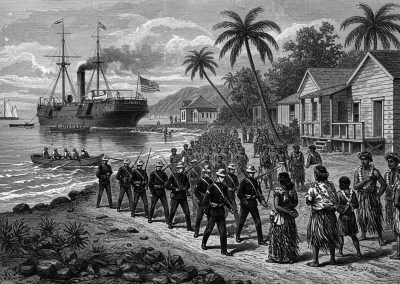

By the late 19th century, the U.S. viewed Hawaii not just as a trading hub but as a strategic military asset. The rise of naval doctrine championed by Alfred Thayer Mahan, including the push for coaling stations and Pacific dominance, made the islands invaluable.

The 1887 establishment of a U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbor, secured through a coercive treaty, was a stepping stone to full annexation. Yet for all the focus on U.S. capital and military expansion, a quieter but influential push came from the American heartland.

WISCONSIN MISSIONARIES AND MORAL IMPERIALISM

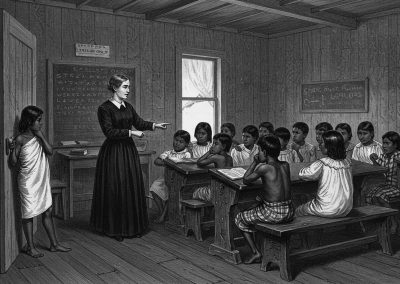

Wisconsin’s Lutheran and Congregationalist communities also contributed some missionaries to the islands throughout the 19th century. Many of these figures helped run Hawaiian schools, churches, and boarding institutions that worked to erode Native Hawaiian culture and language under the guise of Christian salvation.

While the Wisconsin Evangelical Lutheran Synod was not directly active in Hawaii during the 19th century, its theological ethos paralleled the broader American Protestant worldview that often justified expansion as a divine mandate.

These church-led initiatives did not merely spread the Gospel. They created educational and cultural institutions that imposed Western norms, including English-only instruction and the erasure of traditional practices.

Over time, this soft cultural imperialism created a generation of islanders more linguistically and economically tied to the U.S. It was a subtle but effective tool of a cultural arsenal that led to annexation.

MIDWESTERN MONEY MEETS ISLAND SUGAR

Missionaries were only one side of the coin. As sugar plantations grew into Hawaii’s dominant economic engine, Northern capital flowed into the islands. Several Wisconsin investors, including banking firms based in Milwaukee, financed sugar production and land purchases in the late 1800s.

These capital ties were often discreet, funneled through larger East Coast firms or via stockholder arrangements in Hawaiian commercial ventures. Some of these connections came through the booming beet sugar industry in Wisconsin, which viewed Hawaiian cane sugar not as a competitor but as a strategic ally in stabilizing U.S. sugar markets.

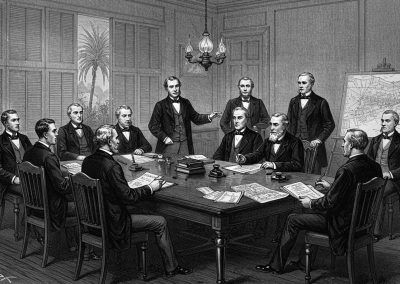

Trade journals from the period show Wisconsin sugar manufacturers lobbying in favor of the annexation bill, seeking tariff-free access to Hawaiian imports under the American flag. More striking were Wisconsin’s political voices in Congress.

While the state did not play a central legislative role in drafting the Newlands Resolution, several Wisconsin representatives and senators voted in favor of it or voiced support in committee records.

At the state level, editorials in city newspapers backed annexation, often echoing racialized and economic arguments that dominated the national conversation. These articles argued that Hawaiian people were “unfit” for self-government and that U.S. intervention would bring “civilization and order.”

FROM THE MIDWEST TO MONARCHY’S FALL

Perhaps the most disturbing Wisconsin connection was in the aftermath of the Hawaiian monarchy’s overthrow in 1893. While the coup was orchestrated by American businessmen and backed by U.S. Marines, the ideological groundwork, particularly the moral and economic rationales, had long been laid by mainland supporters.

Scholars from the University of Wisconsin were among the mainland academics who published works justifying imperial expansion in terms of Manifest Destiny and racial determinism. At least two professors wrote essays in national periodicals advocating annexation, framing it as a civilizational duty.

While their names are largely forgotten today, their work contributed to the atmosphere of justification that enabled Washington’s eventual act. Meanwhile, Wisconsin-born clergy in Honolulu held sermons praising the downfall of the Hawaiian monarchy as a “divine blessing.”

Such public endorsements from Midwestern religious figures gave annexationists both moral cover and momentum.

A QUIET COMPLICITY IN EMPIRE

Wisconsin’s participation in the annexation of Hawaii was never officially documented in state histories, nor did its institutions widely claim credit. Yet the imprint remains in archival letters, church newsletters, corporate records, and political editorials.

It was not the loud voice of conquest, but the steady hum of agreement, a Midwest morality aligned with the conquest of empire from afar.

The University of Wisconsin system, now a network of progressive education and civic engagement, once echoed the same settler logics that underpinned the American occupation of Native land. At the time of Hawaii’s annexation, Wisconsin was less than 50 years removed from its own violent displacement of Ho-Chunk and Ojibwe peoples.

The ideological bridge from Badger State to Pacific archipelago was short. What Wisconsin lacked in proximity, it made up for in influence. Clergymen who authored tracts distributed by national missionary societies, sugar investors who lobbied for federal policy, politicians who took comfort in the strategic gains, and citizens who sent donations to churches eager to “civilize” islanders who had governed themselves for centuries.

In 1898, Wisconsin’s civic and religious institutions stood largely silent, or were supportive, when the U.S. extinguished a sovereign kingdom that had maintained diplomatic relations with global powers.

There were no protest movements from Madison pulpits or Milwaukee streets. No major editorials condemned the seizure. The idea of American superiority, so deeply embedded in post-Civil War Midwestern thought, left little room for Indigenous sovereignty anywhere.

ECHOES THAT LINGER

The consequences of that silence remain visible. Today, Native Hawaiians continue to fight for land rights, language preservation, and cultural survival under a government structure they never consented to join. The long arc of colonization, economic, spiritual, and political, shadows daily life across the islands.

In Wisconsin, some of the religious denominations that once sponsored missionaries to Hawaii have since issued statements acknowledging the harms of cultural erasure. But these gestures, often vague and procedural, have not sparked widespread public reckoning.

There is no state historical marker acknowledging Wisconsin’s role in Hawaii’s annexation. No school curriculum connects the two. The ties, like the guilt, remain unspoken. Historians note that annexation was never a singular event, but the culmination of decades of influence, ideology, and investment.

In this, Wisconsin was complicit. Not in a single act, but in the sustained network of cultural and economic forces that weakened the Hawaiian monarchy from within. Whether through boarding schools that stripped language, or sugar tariffs that favored mainland capital, Wisconsin’s presence in Hawaii was real, enduring, and damaging.

LESSONS FROM AN ERASED CHAPTER

As the U.S. faces new debates about historical memory and systemic injustice, Hawaii’s annexation offers a test of moral clarity. The silence of 1898 cannot be undone, but its lessons remain urgent.

For Wisconsin, that means confronting its own past not only in terms of race relations or tribal history within state borders, but also in how its institutions and citizens participated in the expansion of American power abroad.

It means acknowledging that Midwestern virtue was sometimes a veil for imperial interest, that a state celebrated for its progressive legacy also enabled conquest under the flag of Christian duty and commercial gain.

This legacy challenges the narrative that colonization was merely a coastal endeavor. And it asks Wisconsinites today to reflect not just on what their ancestors did, but what moral choices they failed to make.

In the summer of 1898, the United States claimed the Hawaiian Islands. Wisconsin did not raise the flag, but it helped sew the fabric. From pulpits to plantations, it stood not apart from empire, but quietly behind it.

© Art

Isaac Trevik