American history records the fall of Saigon on April 30, 1975 as the end of the Vietnam War. It happened before that for me, when my father completed his tour of duty there. Growing up in a military home, with stories from the American Civil War to World War 2 and Korea, my perception as small child was that when soldiers came home it meant the war was over.

Basically, the soldiers kept fighting until it was done, because they could not come back until it was “over over there.” So if my father was home, to my way of thinking, everything in Vietnam was over. Until I saw TV news footage showing tanks rolling along the streets of Southern Vietnam and into the Presidential Palace. How could Saigon fall if the war had been over?

As a child trying to make a sense of the war and its impact in my home, surrounded by adults trying and failing to do the very same thing, TV news was the internet of my youth for trying to decipher the mysteries of the world beyond my limited view. TV documentaries about the Vietnam War broadcast concurrently with live news reports from the hot war zones, which I found confusing. How could I be given historical context for a conflict that ended but was still going?

Growing up with films like Apocalypse Now, Full Metal Jacket, Uncommon Valor and Rambo movies in the 1980s, while the nation was trying to collectively heal from the traumatic wounds of Vietnam, also added to my confusion about what to believe. One expert said the war started for this reason, another detailed why the war was lost for that reason. Everyone struggled to explain the complexities of Vietnam in the most simplistic bits.

It did become clear that while every historian I listened to had good insight into an aspect of what happened in Vietnam, no one in the 1980s could actually and coherently explain how we got into the war and why it ended as it did. Being an encyclopedia nerd, I finally started researching Vietnam history on my own. Very little was ever mentioned about the French war or anything proceeding the mid-1960s – before Vietnam became a household word in American living rooms.

Vietnam suffered from Chinese occupation for centuries, followed by French colonialism. During World War 2, the country was occupied by Imperial Japan. After the Japanese signed their surrender on September 2, 1945 aboard the battleship U.S.S. Missouri, there was finally hope within Vietnam that it would finally be an independent and self-ruled nation. But France, with designs to reclaim its pre-war Colonial glory, had other ideas.

It is far too complex a subject to summarize here, and the focus of this column is not to explain the war. I recommend watching the 10-part, 18-hour PBS documentary series from directors Ken Burns and Lynn Novick, The Vietnam War at least once if not twice.

ALSO READ: Lynn Novick: A discussion about her Vietnam War film on Veterans Day

Instead, this is a story about my journey of understanding. And a search for why Vietnam affected my community so deeply, and particularly my father specifically. He would never talk about the war directly, but situations would trigger comments.

I would sneak treasured looks at his medals and military gear, stored in an old steamer trunk kept in the garage. There was a natural fascination to understand and curiosity to explore. Every step towards enlightenment in those early years was followed by dozens of further questions that brought clouds of confusion. The puzzle pieces did not fit together, nor did any of the dots seem to connect.

Like many storybook places, Vietnam existed at a mythical level for me. Some distant land existing only in the past, romanticized in photos and shared stories told like ancient folklore. So as a young adult on my first sabbatical to circumnavigate the Earth, I added Vietnam to my list of global destinations.

I landed in Ho Chi Minh City about the same age as my father, when he was stationed in what was then Saigon in South Vietnam. Officially, Saigon is called Ho Chi Minh City because the North won the civil war. But to those in the south and American veterans, it will always be remembered as Saigon.

I look back at that trip, planned in the early days of the information superhighway on a telephone-based 56k modem and well before social media. The entire journey around the world was an awakening for me. By the time I reach Vietnam, 6 countries later, I was already well along in my process of enlightenment. So I was not chasing the ghost of my father there. And I had nothing for myself I needed to find peace for. I knew that enough time had passed that there would be no answers waiting for me, and I did not go in search of any. Everyone who had looked for answers always seemed to fail.

ALSO READ: Inconvenient Images: How pictures teach us to see the world for what it is

I was simply trying to reconcile what I had been exposed to from afar with what I saw up close, after a gap of nearly a generation. I wanted the first-hand experience, whatever that was, not to walk in my father’s footsteps. I tried to absorb the experiences and touch the physical locations, because they had only existed as the faded images I had grown up seeing for all of my short life. It was also one of the few times in my life that I ever kept a journal.

1997 January 7, Tuesday @ 5:00pm – Sàigòn: I have landed in Sàigòn almost 20 years after my father. I wonder where my life will be 20 years from now, when I am an “old man” reading this, and what lessons I learned from this trip. It took me many years to imagine my father as a young guy. He left for Vietnam at my age. Only I am going on vacation. He went to war.

For whatever reason at the time, I did not write about one of my most profound observations. The American Embassy in Saigon was an icon of the war. Everyone from my generation remembers seeing the documentary films of the last Huey helicopters evacuating from its roof. The terrified surges Vietnamese families trying to secure passage from outside the compound gates before the Americans were gone.

I had already experienced some of the most impressive sights of my life in Asia, from Kyoto to Beijing, to the DMZ at Panmunjom. But to stand at the gates of the former United States Embassy entrance, and see the roof used as a heliport was chilling.

The ghost of that departing Huey was clear when I stood at the spot where TV news crews had filmed two decades earlier. And most unnerving of all was that its position from the compound gate was far closer than I could ever have imagined. It was a distance that I could have hit with a well thrown baseball. A year after my visit to Saigon, the embassy was torn down as the city began reshaping its skyline.

1997 January 9, Thursday @ 9:55pm – Sàigòn: What a contrasting afternoon. Up to my elbows in poverty, then rubbing those elbows with the clean and polished trendy people at the mega-bowling alley. Everyone was excited to learn that I was from Milwaukee, known as a bowling capital. Sadly, I never developed bowling skills and scored poorly. It shocked the group who expected more from me, but someone said they respected my attempt to play badly to honor my hosts. No, I was just that bad but at least Milwaukee’s bowling reputation was not unforgivably tarnished.

Growing up in rural and suburban areas, I knew the difference between city and country environments. But when I was in Saigon, it seemed that anything that was not city was the jungle. That was my limited perception of any swash of vegetation, being indistinguishable from farmland and actual inhospitable regions of the country where the war was fought. It was so hot and humid in January – worse than Savannah, Georgia in April – that just getting around the city was exhausting, I could not imaging being in the rural regions, let alone doing so in combat conditions.

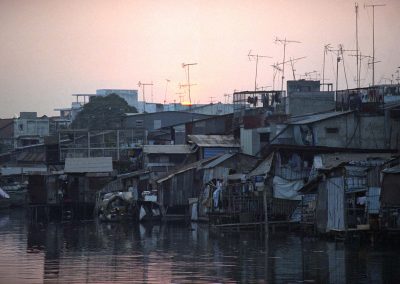

1997 January 11, Saturday @ 12:29am – Ho Chi Minh City: Spent several hours in the morning heat on a motorcycle to travel outside of the city. We went Northeast to the Binh Quoi Tourist Village in the Bình Thạnh District. We rented a boat for an hour to take us along the Sàigòn River and I got to see the countryside for the first time. It is very beautiful and tropically lush. But I would not want to set foot in that jungle today, let alone in war.

My sabbatical was basically a backpack trip across the globe, so I had limited cloths and was always trying to stay clean. That task became more difficult by the time I got to Southeast Asia for many reasons. What I also remember most about the visit to Vietnam were things like, street vendors sold insects encased in amber due to the popularity of Jurassic Park, amazement that young women could wear perfectly white áo dài outfits all day and stay clean – when I was already dirty the moment after putting on fresh clothing.

And, the poverty. At that time in my worldly experience it was overwhelming and more acute than anywhere else I had been previously exposed.

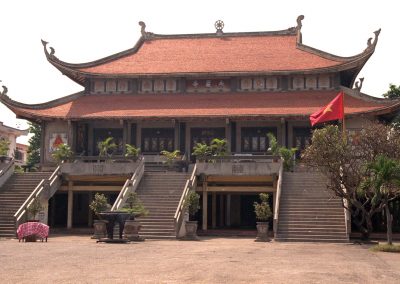

In Vietnam, where America was seen as the invading enemy that was finally driven out, the monuments were not kind. That memory has stayed with me, and remains relevant today, that there are parts of the world where our country and its actions are not beloved. While there are monuments to Americans as heroes that we are as a culture are familiar with, that view and historical narrative is not universally shared.

1997 January 8, Wednesday @ 1:30pm – Sàigòn: The “War Crimes” Museum was harder to digest than Hiroshima. At first I was proud when I saw the patches my father wore were displayed by strategic history maps. Later, after seeing many of the shocking photos, I felt the horror of what took place. The War is more personal than WWII because of my Father. This was the first time I came face to face with it on Vietnamese soil, not on a TV back home. There was such brutality on both sides during the war, and reunification had not ended the hardships. Seeing how the people live and what they endure here explains what I see at home in America.

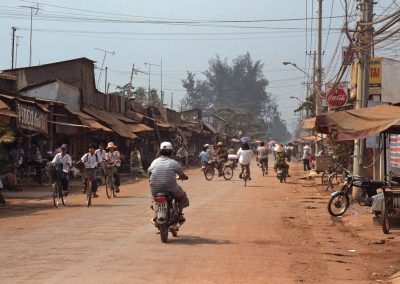

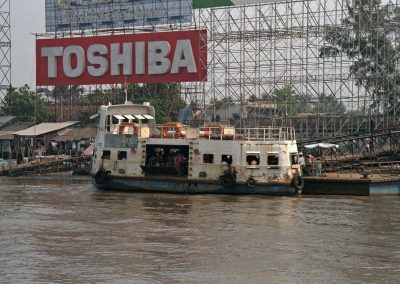

When I walked through the Old French Quarter in Ho Chi Minh City, the atmosphere still felt stuck in the 1960s. The big pushes for economic reform were only beginning at that time. The 1997 Asian financial crisis has just hit a few months earlier, and the United States would not sign the historic Bilateral Trade Agreement with Vietnam until almost 3 years later in July 2000.

I was very focused on slices of life and historic details with the photos I took. Considering I only had 24 frames per roll to work with, I still managed to take an extraordinary amount of photos, 306 to be exact. I wish I had been more documentary minded at that time, to capture images that would be show conditions before so much change occurred. I did not develop that sensibility until I moved to China a few years later.

I only saw a handful of private cars during my two weeks of exploring the city. By 2000, I heard cars were overwhelming the streets that had been clogged with bicycles and scooters during my visit and the previous years.

April 30 1975 is the date that American history booked closed the chapter on the Vietnam War, 44 years ago. The images that I took on 35mm film in 1997 are a last look at Saigon before it transitioned from its legacy of war and into an economic engine.

- Inconvenient Images: How pictures teach us to see the world for what it is

- Milwaukee’s hometown Air Wing kicks off Armed Forces Week with aerial refueling flight

- William Pelkofer: Wisconsin Air National Guardsman takes home-grown path for pilot training

- Dawn of the Red Arrow: Documentary details birth of Wisconsin’s 32nd Division in World War I

- Bay View students revive Lance P. Sijan Memorial Scholarship as example of leadership, love, and honor

- Brewers legend Robin Yount recognized for years of citizen involvement in helping the Armed Forces

- Gold star family, George Banda, and Iwo Jima veterans recognized with Sijan award for valor

- Veterans Day Parade 2018 honors Milwaukee’s Red Arrow Division for its WWI service

- Milwaukee Notebook: Red Arrow, the Park that Moved

- Janine Sijan Rozina: A story not of war but the spirit of love

- “Sijan” and Chip Duncan’s “The First Patient” among world premieres at Milwaukee Film Festival

- Fellow POWs honor their fallen brother at Sijan Plaza dedication

- Photo Essay: Preview of Sijan Plaza and memorials of honor

- Photo Essay: An example of courage installed at Mitchell Airport

- Ben Domian: a life influenced by family and Lance Sijan

- Vietnam combat medic George Banda honored at tribute to Latino veterans

- Lynn Novick: A discussion about her Vietnam War film on Veterans Day

- The irony of visiting heroes at Arlington, the former home of a national traitor

- Photo Essay: Seeing the Nation’s Capital with Milwaukee Eyes

- George Banda: Honoring lost friends in vigil to Vietnam veterans at The Wall

- Maya Lin: Ceremony marks 35th anniversary of Vietnam Memorial’s healing power

- George Banda: The Humble Hero

- Audio: An American story from Mexico to Vietnam

- Purple Heart Day honors Milwaukee’s wounded veterans

- Photo Essay: Milwaukee’s 54th Annual Veterans Day Parade salutes hometown heroes

- Online patriots too lazy to honor troops by actually attending Veterans Day Parade

- Thank You, Canada, for loving Milwaukee Veterans

- Aerial demonstration squadrons announced for 2019 Air & Water Show

- Flying with the Golden Knights during the Milwaukee Air & Water Show

- Air & Water Show 2018 performances prepared and waited for weather to clear

- Exclusive: 360° view of skydive at 2,000 feet over Milwaukee with precision landing

- Video: Army’s elite parachute demonstration team descends over lakefront

- Airshow sees Army Parachute Team descend through the atmosphere

- Photo Essay: Golden Knights Practice Jump attempt at 2,000 feet

- Photo Essay: Golden Knights Precision Landing from 12,500 feet

- Photo Essay: Free-falling with the Golden Knights Demonstration Team

- Video: U.S. Army Golden Knights parachute into Milwaukee Airshow

Lee Matz