The highly anticipated upsurge of flight activity post-COVID vaccine at Milwaukee Mitchell International Airport is second only to the surge expected 75 years ago this month. In April 1946 “Camp Billy Mitchell,” Milwaukee’s prisoner of war work camp, was finally decommissioned.

The closure made way for Milwaukee County’s long-delayed post-war civilian air travel to soar. However, the War Department’s continued “squatting” would delay the anxiously anticipated air travel rush from taking flight for another two years.

Between 1945 and 1946, over 3000 German prisoners of war (PW’s was the abbreviation used in 1945) were interned at General Mitchell Field, frustrating all but minimal civilian flight use and access. Before and throughout the internment, Milwaukee County officials and towns were actively debating potential County airport expansion and additional locations to seize upon the economic explosion in post-World War II airfreight and flight.

However, the Army’s Camp Billy Mitchell occupation of acres of Milwaukee County’s only public airfield hampered civilian-use planning. Further, exasperatingly, Camp Billy Mitchell was not only the last of Wisconsin’s 38 PW work camps to shut down but also it was not shuttered by the military for almost two years after it was “officially” closed.

Camp Billy Mitchell Opens

In1943, the Army had a problem: what to do with thousands of captured German troops. After a successful North African Campaign in 1943, the military strategically determined that the most secure detention of 400,000 PW’s required relocating them to the United States. Texas facilities held the PW’s for one year. Wisconsin cities were tapped to receive 40,000 PW’s in 38 newly-created work camps.

Beginning in December 1944, over 300 Jamaican nationals, working in war-time Milwaukee’s foundries and residing in Mitchell Field’s abandoned airpilot barracks, were displaced by the Army for the pending arrival of German combatants.

On January 4, 1945, the County signed a six-month lease for $1.00, renting a large swath of Mitchell Field to the U.S. War Department for use as a World War II prisoner-of-war camp. During the next 15 months, over 3,000 German prisoners, and over 50 U.S. Army officers and 250 enlisted men lived in the work camp.

Temporary “disciplinary” barracks, mess halls, workshops, and a hospital were added to the grounds along its Grange Avenue border. The Army converted an existing hangar into camp workshops. The two-story passenger terminal building, constructed in 1940 by the Works Progress Administration, remained in County control with limited civilian operations and purposes.

Wisconsin was considered a favored location due to its still thriving German heritage, language, and culture. However, Wisconsin internments also raised military intelligence concerns. There was the potential exacerbation of persistent local Bund activities (which included a Bund training camp in Grafton, Wisconsin), and potential interference by local German-Americans and European refugees swarming the camps to identify and unite with kin.

To quell the former concern, only non-political soldiers were sent to Wisconsin. To quell the latter concern, the Army initially “classified” the establishment of the camps, and, in turn, the detainees within them.

However, in short order, the military lifted the ban about reporting on Camp Billy Mitchell PW’s. With the help of the Red Cross, local citizens were notified about any recently arrived relatives. Over time, the camp commander established detailed visitor protocols and restrictions, such as family-only visits once per month for no more than an hour with limited gifts.

The Milwaukee newspapers regularly reported about Camp Billy Mitchell during the over 36 months it occupied the airfield. The first 1500 internees arrived on January 10 and the first “escapees” were caught by Milwaukee police on January 13. The Milwaukee Journal recounted in detail the police interview of the two wandering PW’s. They were stopped because they matched the description of some check fraud conspirator – and also because they rose suspicions by wearing their coats inside out.

The PW’s explained that they did not want the white-painted “PW” on the back of the coats to be seen. The news article was conversational, including a profuse message of thanks to the police officers for their kind treatment. The PW’s explained to reporters that they heard about the large number of German-Milwaukeeans, but did not know about the city’s significant Polish population.

They confessed to exploring the city, enjoying the dance hall polkas, seeking some famed beer for consumption, and were planning to return to the camp before dawn. The article was part news story, part police report, and part propaganda – to both assuage concerns of the PW’s dangerousness and to assert the need for more comprehensive security measures.

Within two weeks, local newspapers reported on January 29, 1945, about the newly constructed guard towers with searchlights. The additions reportedly enhanced the compound’s security that already had included an interior fence and an exterior fence topped with barbed wire.

Within a month thereafter, the officer-in-charge and the public relations officer from Fort Sheridan, Illinois conducted a press tour. The tour confirmed that the work camps followed the Geneva Conventions. PW’s were not required to work but then they would forego the hourly payment, equal to 80% of civilian workers’ minimum wage.

Monthly wages were paid in the form of camp script. The script could only be used in two ways: deposited in government-sponsored savings accounts or used at the camp store to purchase sundries. The camp store offerings were conventional and available to all camp residents. However, the camp store did have its own regulations, e.g., PW’s could not buy “brand” cigarettes, and PW’s could only buy one bottle of beer per day.

Upon opening, Camp Billy Mitchell initially contracted only with Milwaukee’s Assembly Battery Company (a newly-created affiliate of Ray-O-Vac) to make batteries for radio testing. During the press tour, reporters saw the two conveyor systems in the National Guard Armory where the PW’s worked on the then-largest battery assembly lines in the nation.

During the camp’s 15 months of operation, the PW’s handled 10 million battery cells, and produced thousands of small batteries; in the first three operating months, the U.S. Treasury collected over $150,000 under the battery work contract alone.

The work camp contracts brought thousands of dollars to the Army, offsetting prisoner of war costs. Eventually, additional government contracts were procured, e.g., PW’s were transported to the State Fairgrounds to work in its horse stables; or to unload, store and then pack locally harvested potatoes, beets, and carrots to ship for canning and processing.

With war-depleted workforces, private businesses began to seek work contracts with the camp. Soon daily transports of thousands of PW’s arrived at sites such as Burlington’s Nestle’s Condensed Milk Cannery, Oak Creek’s A. C. Spark Plug factory, Milwaukee’s Tichy confectionaries, and Franksville’s Frank Pure Food Company’s cabbage fields, sauerkraut factory, and spinach cannery. In 1945 alone the U. S. Treasury collected over $265,000 from private company workcamp contracts.

To house additional prisoners of war sent to Milwaukee, the U. S. Army also acquired the County’s “prison farm” at its House of Correction, located on a 400-acre site on Silver Spring Avenue across from McGovern Park. After the war, the Army used the site as a military prison. By 1950 the facilities were repurposed to ease the housing shortage for World War II veterans. Several years later, the City of Milwaukee would construct a housing project on the property.

While the Camp Billy Mitchell officers disciplined about 50 internees during the camp’s operation, no one actually attempted to escape. Reasons abounded for the lack of AWOL incidents, but practical ones prevailed. To where would one escape? Continued detainment and residence in the camp were a prisoner’s secure option.

A prisoner did not know about the state of his family or the states of Europe or his homeland or have the means to return. Another deterrent: the guards had the authority to shoot any PW attempting to escape or leave without permission. All officers and guards were armed everywhere in the camp, except in the barracks.

(The two internees who wandered Milwaukee in January 1945 were not shot upon returning to Camp Billy Mitchell because the authority to shoot, curiously, extended only if one was leaving the camp.)

Another persuasive reason for staying on-site was the camp’s offerings. Camp Billy Mitchell provided food, housing, work wages, camaraderie with co-workers and bunkmates, and other amenities. The PW’s enjoyed privileges by working in the mess and on the grounds. The prisoners wrote and published a monthly newspaper (albeit censored) to be distributed among themselves.

Bi-lingual prisoners daily translated the New York Times for German-only speakers. Religious services were held regularly by a Catholic chaplain. A few dogs were permitted as camp pets; an orange and white cat, Mickle, was deemed the camp’s mascot. Radios were available as means of providing PWs with accurate reports about America’s mounting wartime successes, while also providing entertainment and sports coverage.

The PW’s other entertainments included a thriving social scene – singing, writing, movies, and creative arts. In fact, a prisoner art exhibit opened at Camp Billy Mitchell in May 1945, with press coverage that included three drawings published on the front page of the May 23, 1945, Milwaukee Sentinel. Wood art and paintings were created by prisoners with materials and art supplies bought with camp script. Of the 82 paintings in the exhibit’s opening, 26 were bought within the first day. The newspaper review complimented the talent, adding that “there was no ripple of so-called modernism. Even the nudes were decorous and law abiding.”

Post-V-E Day and Post-V-J Day

In May 1945, victory in Europe was declared. While the German internees were still prisoners of war, however, they did not pose the same “enemy threat” as they had before V-E Day. Thereafter the camp’s rule enforcement gradually became more relaxed. By late summer, PW’s were seizing the “earned” opportunity to frequent pubs along South Howell Avenue.

The Milwaukee PW’s only gradually left the camp, most eventually wending to Europe to be repatriated. An October 31, 1945 farewell party for about 200 enlisted soldiers was mistaken for the camp closing party. A misleading article required a news report two days later that in fact the camp remained activated. The public was reassured in November 1945 that the PW’s would continue working the beet and potato harvest and processing.

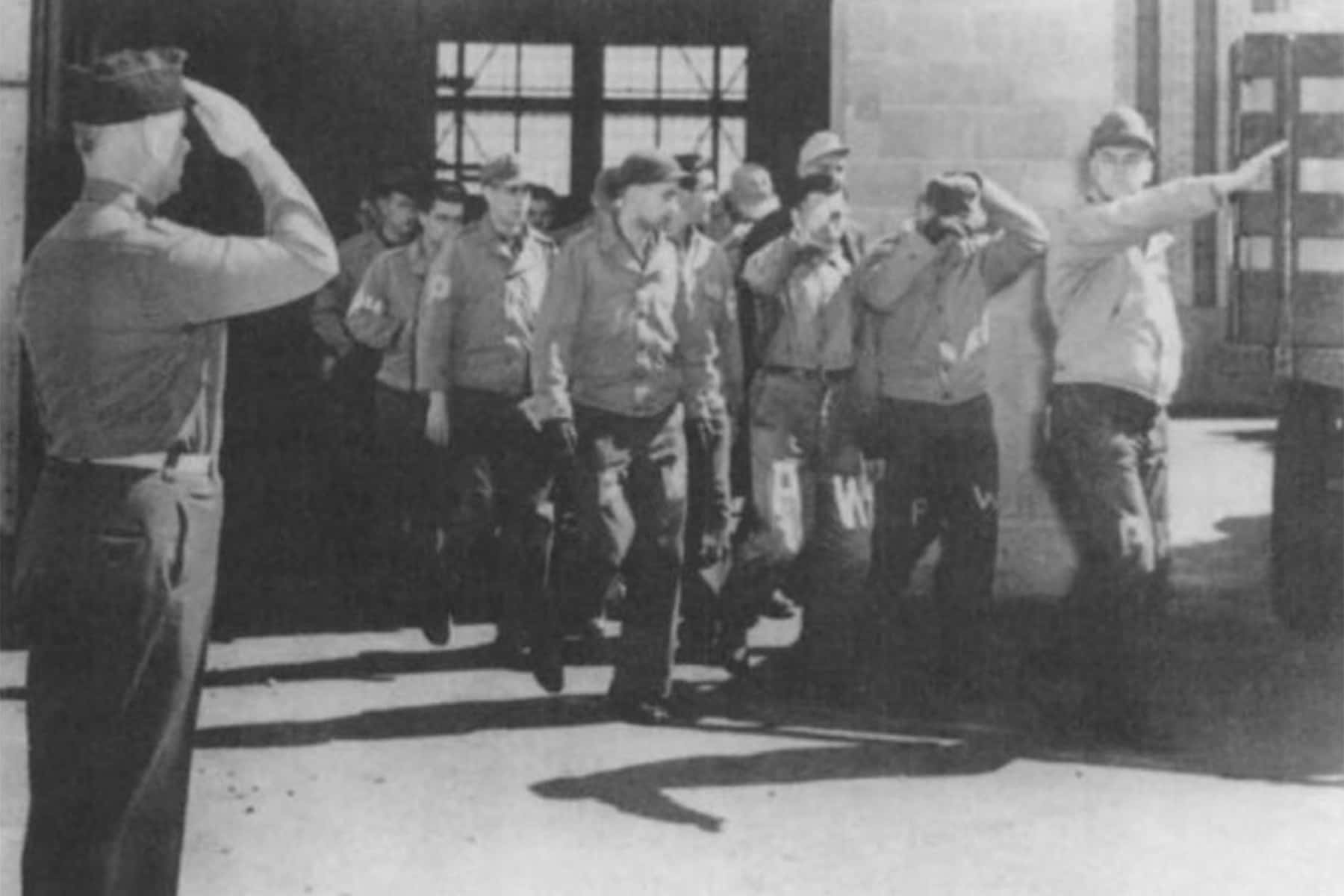

In early 1946, about 2,300 internees remained at Camp Billy Mitchell with staffing reduced to about 30 guards. On April 1, 1946, the 12 remaining Camp Billy Mitchell PW’s were transferred to Fort Sheridan, Illinois. A military band ceremony added some flourish to the official internment closing.

The War Department had long since exceeded the end date of its six-month-one-dollar-war-emergency lease. Even though the camp officially “closed” on April 1, 1946, the control of the property was not transferred back to the County until February 1948. As early as September 25, 1945, the County began adopting resolutions to again terminate the War Department’s occupation, but to no avail.

An “eviction” was of the essence. For several years Milwaukee County actively planned for expanding its post-war air flight and freight, and for competing with other cities for commercial and travel business. Throughout the early 1940s, the County Board (led by Supervisor Lawrence Timmerman) explored options, sought business input, collected economic and flight data from other cities, and debated private-versus-public airfield developments.

Eventually, twelve additional airport locations were identified, with one option being an expansion of General Mitchell Field. Unlike other Wisconsin counties, Milwaukee County’s townships could vote to decline airfield placement. The Towns of Granville, Wauwatosa, and Greenfield all opposed or declined airport sitings. The “Maitland” proposal, which included siting an airstrip in downtown Milwaukee, ultimately was thwarted.

After many hearings and much consideration, public officials opted to expand Mitchell Field into the Town of Lake. While the municipality and its residents adamantly opposed the decision, eventually the County purchased 75 properties (mostly homes) and an additional 770 acres of land contiguous to the still-Army-occupied airfield. Milwaukee County would acquire a second public airfield in 1949. The second landing strip, originally built as a private venture on the north side of the City of Milwaukee, eventually would be renamed Timmerman Airport.

Irrespective of the County’s plan, the federal government had its own ideas about using the former Camp Billy Mitchell grounds, including appropriating the vacant installation for veteran housing. After abandoning that plan in 1947, the War Department offered the temporary barracks to local American Legion and American Veterans of Foreign War Posts for adaptive reuse. The Department’s offer of the buildings came with two contingencies: the VFW paying $600.00, and the VFW dismantling and moving the buildings to its own location.

At least three posts took up the deal: Greendale’s American Legion Post #416, Oak Creek’s Oelschlaeger-Dallmann American Legion Post #434, and Bay View’s Travis AMVETS Post #12 of the American Legion. Piece-by-piece the barracks were deconstructed, moved, and reconstructed, again piece by piece, as clubhouses.

Without property of its own, the Bay View American Legion rented lake-view property from the Harbor Commission in 1947 for $1.00 per year. It took until 1949 for the VFW to prepare the Conway Street land for barrack placement, and to transport the beams and boards for the barracks’ reconstruction.

The Post sold the building in 1996 to the owners and operators of Dom & Phil DeMarini’s Pizza. The deal also came with a contingency: the distinctive American flag pole, donated and dedicated by the family of a local Korean Conflict soldier killed-in-action, could not be destroyed or removed from its prominent location on the hill’s crest.

So, as it did 75 years ago, the flag still flies over Camp Billy Mitchell barracks.

© Photo

Milwaukee Public Library and Milwaukee County Historical Society