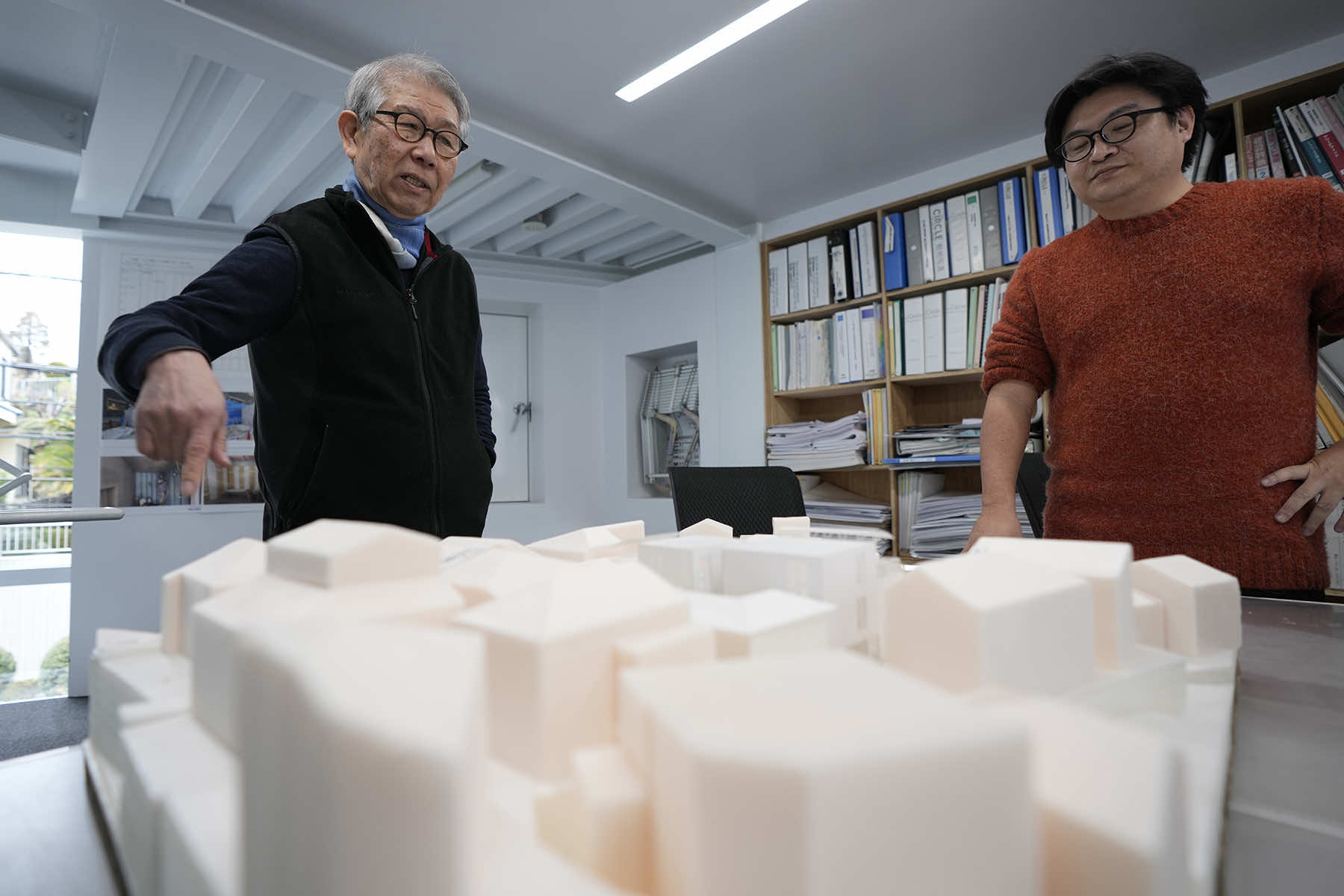

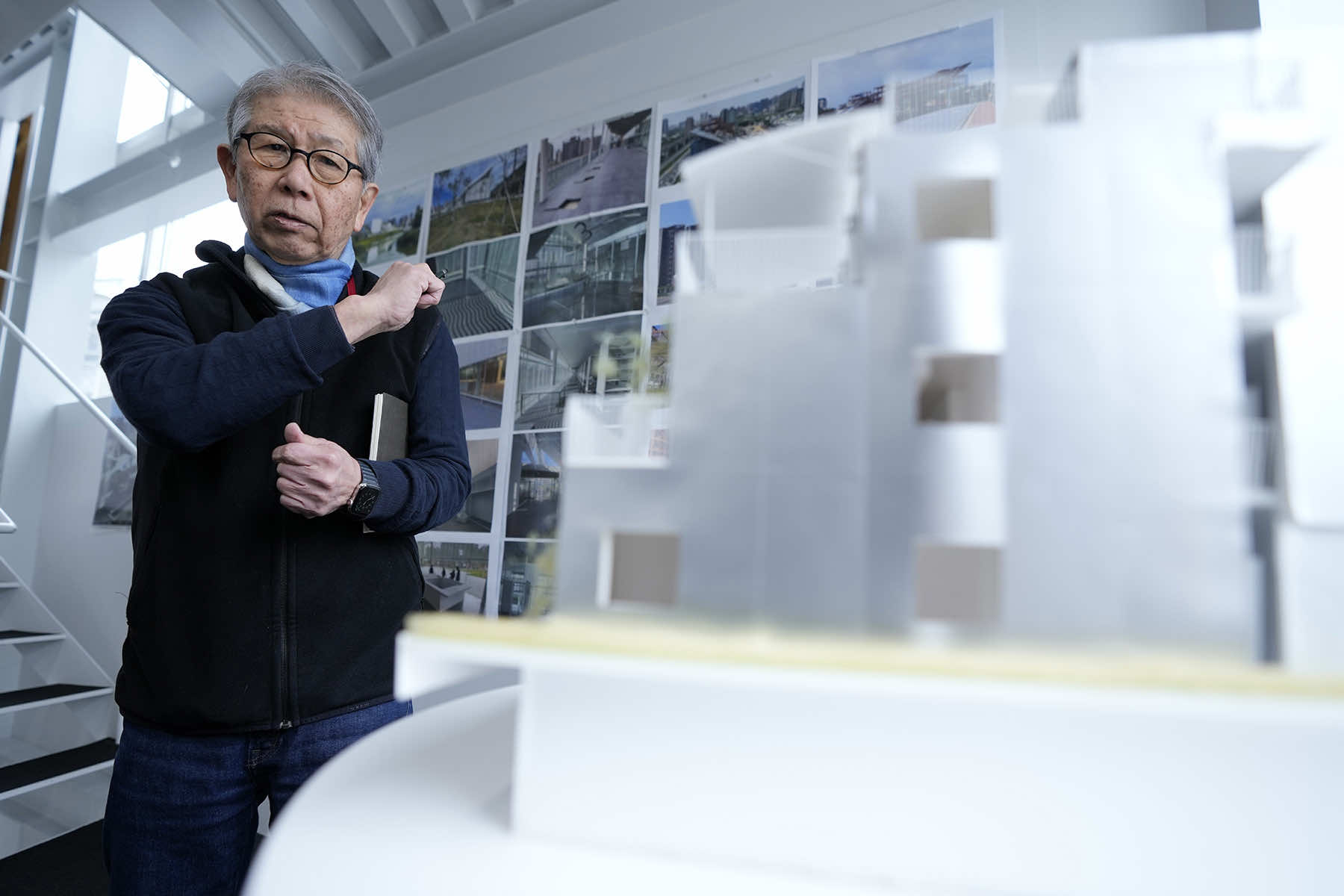

The Pritzker Architecture Prize was awarded to Japan’s Riken Yamamoto in March, who earned the field’s highest honor for what organizers described as a long career focused on “multiplying opportunities for people to meet spontaneously, through precise, rational design strategies.”

Yamamoto, 78, has spent a five-decade career designing both private and public buildings — from residences to museums to schools, from a bustling airport center to a glass-walled fire station — and prizing a spirit of community in all spaces.

“By the strong, consistent quality of his buildings, he aims to dignify, enhance and enrich the lives of individuals — from children to elders — and their social connections,” the jury said, in part, in the citation. “For him, a building has a public function even when it is private.”

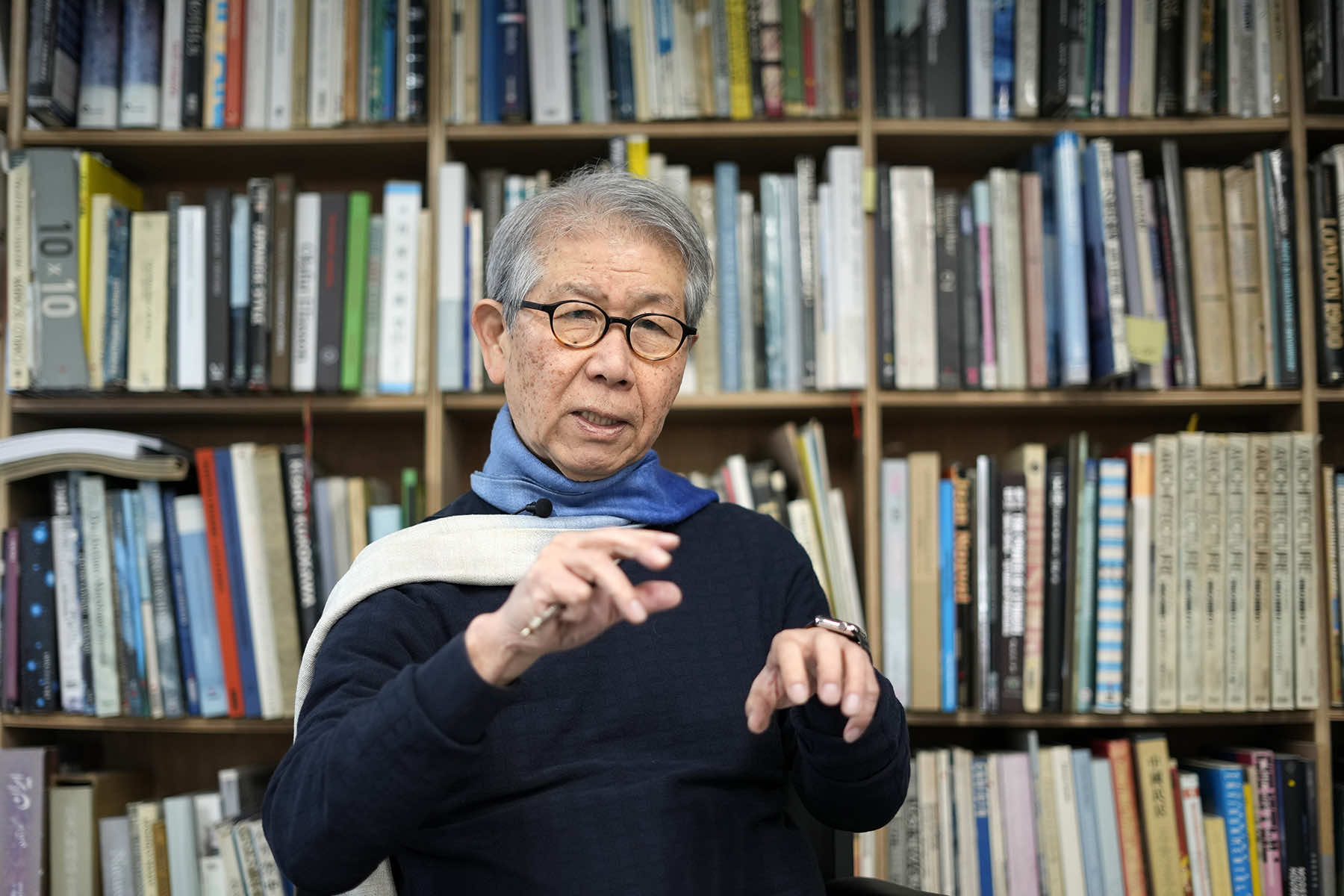

In an interview from Yokohama, where he is based, Yamamoto said he was both proud and “amazed” to win the prize, seen as the Nobel of Architecture, at this point in his career.

“Soon I will be 79 years old,” he said. “This prize is a big moment for me. In the near future I think many people will listen to me very carefully. Maybe I can say my opinion more easily than before.”

The architect explained that his craft was not simply to design buildings, but to design in the context of their surroundings, and hopefully to impact the surroundings as well.

A key example is Yamamoto’s virtually transparent Hiroshima Nishi Fire Station, designed in 2000, with a facade, interior walls, and floors made of glass. The building invites the public to experience the daily activities of firefighters, something it rarely sees.

The result of the composition encourages passersby “to view and engage with those who are protecting the community, resulting in a reciprocal commitment between the civil servants and the citizens they serve,” organizers said.

Normally a fire station would be built from concrete, said Yamamoto, but he had a different perspective, which he submitted in a competition with other architects.

“I proposed a very radical idea,” Yamamoto said. “The idea was that the fire house should be the center of the community. Not only their fire work but their daily life should be the center, because they are living at the place, for 24 hours they have activities.”

He described firefighters training with ropes and ladders in a central atrium visible from outside. Yamamoto said that he was pleased to watch how the public has responded to the design.

“Many young children come to see,” he said. “It’s very interesting for them.”

A more recent design with a similar concept is The Circle at Zurich’s airport, designed in 2020, a major commercial center for shops, restaurants, hotels and a convention hall. Yamamoto said he aimed to create an open, 24-hour hour environment, a space to welcome city residents as well as travelers.

“I proposed a very open system,” he said, “no gate, no entrance, no door.” He said snow or rain sometimes enters the space via a partially open roof.

Another noted design is the Hotakubo housing project in Kumamoto, Japan, Yamamoto’s first social housing project, made up of 110 homes in 16 “clusters.”

“It is very difficult. How do you make a community out of 110 family houses?” he mused in an interview about the 1991 design.

Most apartments, he noted, are boxes inside of a bigger box.

“It’s very easy to create privacy, but very difficult to make a community because each house is independent,” he said.

But the architect found a creative solution, a tree-lined plaza at the center that can only be entered via a residence. He was able to combine the private with the public, giving individual families their privacy while promoting connections between them. Terraces also overlook the common space.

Yamamoto was born in China in 1945 and raised in Japan from early childhood. He said he first grew attracted to architecture while still in high school. He received a master’s degree in architecture from Tokyo University in 1971, and founded his own practice two years later.

Many of his ideas on community were inspired by extensive trips he took early in his career — not to famous monuments but instead to villages in Europe, North Africa, Latin America, the Middle East, and Asia.

In such villages, Yamamoto examined the relationship of the family unit to the broader community and explored the idea of a “threshold” between public and private space. He also said he was inspired by the writings of philosopher Hannah Arendt.

A book by Yamamoto, “The Space of Power, The Power of Space,” is due to be published in October, an English translation of his 2015 work.

Yamamoto, who lives and works in Yokohama and has held numerous teaching positions, is the 53rd laureate of the Pritzker Architecture Prize, established in 1979 by the late entrepreneur Jay A. Pritzker and his wife, Cindy. Winners receive a $100,000 grant and a bronze medallion.

3.11 Exploring Fukushima

- Journey to Japan: A photojournalist’s diary from the ruins of Tōhoku 13 years later

- Timeline of Tragedy: A look back at the long struggle since Fukushima's 2011 triple disaster

- New Year's Aftershock: Memories of Fukushima fuels concern for recovery in Noto Peninsula

- Lessons for future generations: Memorial Museum in Futaba marks 13 years since 3.11 Disaster

- In Silence and Solidarity: Japan Remembers the thousands lost to earthquake and tsunami in 2011

- Fukushima's Legacy: Condition of melted nuclear reactors still unclear 13 years after disaster

- Seafood Safety: Profits surge as Japanese consumers rally behind Fukushima's fishing industry

- Radioactive Waste: IAEA confirms water discharge from ruined nuclear plant meets safety standards

- Technical Hurdles for TEPCO: Critics question 2051 deadline for decommissioning Fukushima

- In the shadow of silence: Exploring Fukushima's abandoned lands that remain frozen in time

- Spiral Staircase of Life: Tōhoku museums preserve echoes of March 11 for future generations

- Retracing Our Steps: A review of the project that documented nuclear refugees returning home

- Noriko Abe: Continuing a family legacy of hospitality to guide Minamisanriku's recovery

- Voices of Kataribe: Storytellers share personal accounts of earthquake and tsunami in Tōhoku

- Moai of Minamisanriku: How a bond with Chile forged a learning hub for disaster preparedness

- Focus on the Future: Futaba Project aims to rebuild dreams and repopulate its community

- Junko Yagi: Pioneering a grassroots revival of local businesses in rural Onagawa

- Diving into darkness: The story of Yasuo Takamatsu's search for his missing wife

- Solace and Sake: Chūson-ji Temple and Sekinoichi Shuzo share centuries of tradition in Iwate

- Heartbeat of Miyagi: Community center offers space to engage with Sendai's unyielding spirit

- Unseen Scars: Survivors in Tōhoku reflect on more than a decade of trauma, recovery, and hope

- Running into history: The day Milwaukee Independent stumbled upon a marathon in Tokyo

- Roman Kashpur: Ukrainian war hero conquers Tokyo Marathon 2024 with prosthetic leg

- From Rails to Roads: BRT offers flexible transit solutions for disaster-struck communities

- From Snow to Sakura: Japan’s cherry blossom season feels economic impact of climate change

- Potholes on the Manga Road: Ishinomaki and Kamakura navigate the challenges of anime tourism

- The Ako Incident: Honoring the 47 Ronin’s legendary samurai loyalty at Sengakuji Temple

- "Shōgun" Reimagined: Ambitious TV series updates epic historical drama about feudal Japan

- Enchanting Hollywood: Japanese cinema celebrates Oscar wins by Hayao Miyazaki and Godzilla

- Toxic Tourists: Geisha District in Kyoto cracks down on over-zealous visitors with new rules

- Medieval Healing: "The Tale of Genji" offers insight into mysteries of Japanese medicine

- Aesthetic of Wabi-Sabi: Finding beauty and harmony in the unfinished and imperfect

- Riken Yamamoto: Japanese architect wins Pritzker Prize for community-centric designs

Jocelyn Noveck and MI Staff (Japan)

Eugene Hoshiko (AP)

3.11 Exploring Fukushima: The Tōhoku region of Japan experienced one of the worst natural disasters ever recorded when a powerful earthquake was followed by a massive tsunami, and triggered an unprecedented nuclear crisis in 2011. With a personal connection to the tragedies, Milwaukee Independent returned for the first time in 13 years to attend events commemorating the March 11 anniversary. The purpose of the journalism project included interviews with survivors about their challenges over the past decade, reviews of rebuilt cities that had been washed away by the ocean, and visits to newly opened areas that had been left barren by radiation. This special editorial series offers a detailed look at a situation that will continue to have a daily global impact for generations. mkeind.com/exploringfukushima