Before Oshkosh became synonymous with the world’s largest aviation gathering, it was the suburbs of Milwaukee that quietly seeded the grassroots revolution of experimental flight.

In 1953, Paul Poberezny, a World War II pilot and aircraft mechanic, founded what would become the Experimental Aircraft Association in the garage of his Hales Corners home, just southwest of downtown Milwaukee.

That modest beginning — fueled by scrap metal, hand-drawn blueprints, and a belief that flight should be accessible to ordinary citizens — ignited a movement that still defines homebuilt aviation across the country.

The first official EAA fly-in took place that same year at Curtiss-Wright Field, today known as Lawrence J. Timmerman Airport. It was a modest affair, held in conjunction with the Milwaukee Air Pageant.

But for a handful of early builders and tinkerers, it represented something much larger. It was an acknowledgment that innovation didn’t have to come from corporate hangars or government labs. It could be coaxed into existence from a garage, a barn, or a machine shop tucked behind a suburban ranch house.

Milwaukee wasn’t just a backdrop for EAA’s early years. It was the crucible in which the association’s ethos was forged. Poberezny’s decision to locate the group’s first headquarters in Franklin, a quiet Milwaukee suburb, spoke to the accessibility and everyman appeal that EAA promoted.

The city, with its industrial know-how and Midwestern work ethic, proved fertile ground for amateur builders who saw no contradiction between weekend hobbyism and serious engineering. According to EAA archival material, Poberezny frequently credited Milwaukee’s industrial character and local talent as critical to the group’s formative years. He emphasized that the community’s ability to build, improvise, and collaborate shaped the association’s hands-on culture.

That spirit was visible at the earliest fly-ins, where builders parked their aircraft on grass fields, swapped schematics under open hangars, and traded war stories and welding tips in equal measure. While many participants came from across Wisconsin, Illinois, and Minnesota, a disproportionate number hailed from Milwaukee County and the surrounding suburbs.

Their fingerprints remain on the early documentation of EAA—minutes from meetings held in local basements, newsletters mimeographed at Milwaukee print shops, and black-and-white photographs of taildragger prototypes snapped against the skyline of downtown.

By the late 1950s, the growth of the annual fly-in forced EAA to relocate to Rockford, Illinois. But the move didn’t sever Milwaukee’s link. The new location simply provided more runway space. Many of the original organizers, volunteers, and builders continued to reside and work in Milwaukee.

Even after EAA’s permanent shift to Oshkosh in 1970, Milwaukee retained a symbolic and practical connection to the association’s past—and a vested interest in its future. One of the clearest manifestations of that relationship was the continuity of Milwaukee-based builders who remained deeply embedded in the homebuilt movement.

Builders across Milwaukee’s suburbs, including many former industrial workers, played a key role in sustaining the experimental aircraft movement in the 1960s. These early hobbyists often worked out of their garages or basements, crafting wood-and-fabric airframes with salvaged parts and detailed plans acquired through EAA connections or technical manuals. Several appeared in early editions of Sport Aviation, offering practical insight into a culture of persistence over pedigree.

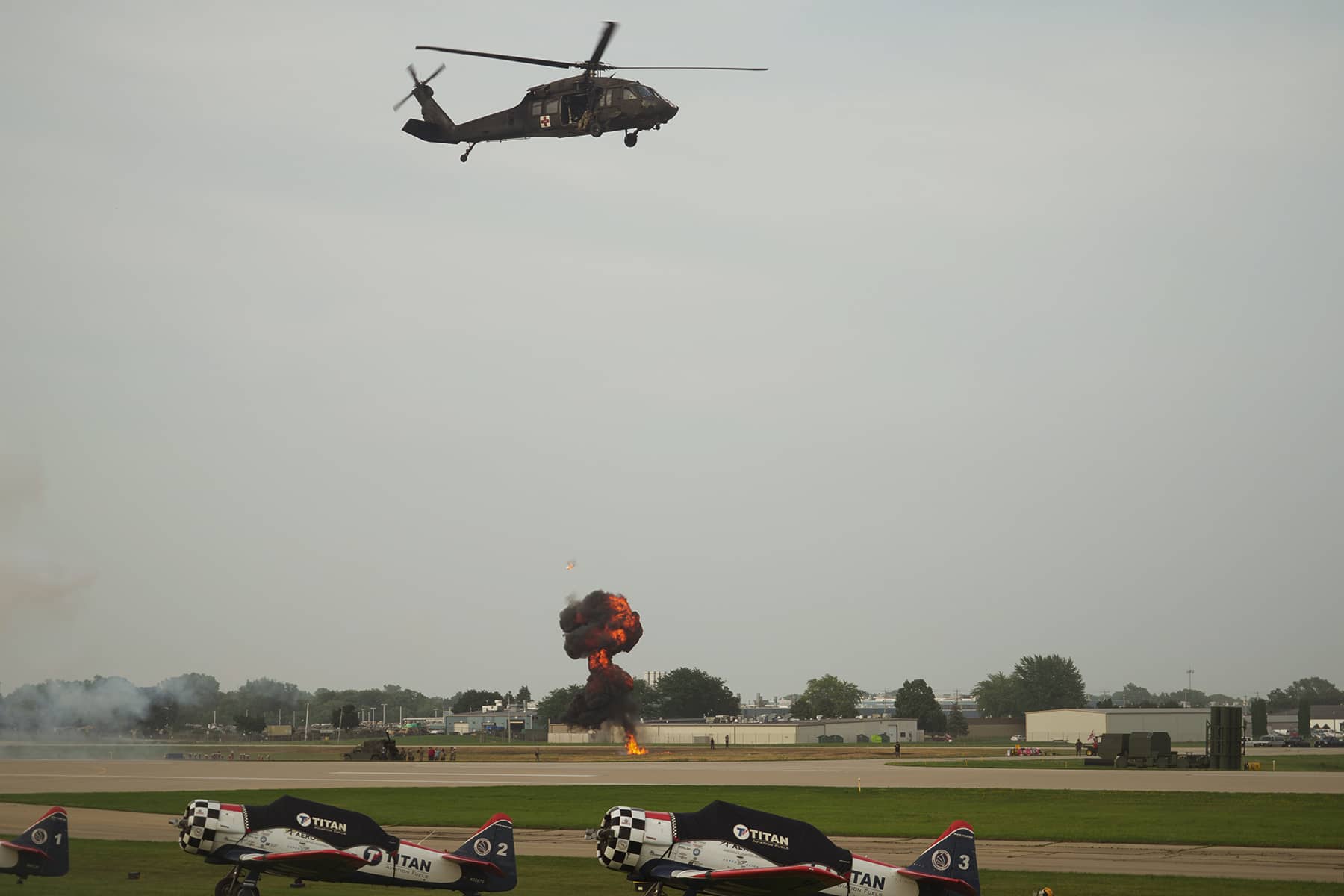

While the Milwaukee Air Pageant no longer exists, its legacy can be found in the early DNA of the EAA. The pageant, once a staple of Milwaukee’s civic calendar, combined military demonstrations with civilian stunts and experimental showcases. It was within that mixed environment — part entertainment, part engineering exhibition — that EAA found its first major public platform.

That overlap between spectacle and substance defined the tone of early EAA fly-ins. The events were not merely technical forums. They were also communal celebrations of ingenuity, with children climbing into cockpits and families picnicking alongside aircraft built from scratch. Milwaukee’s aviation scene lent both logistical support and a receptive audience for what was, in many ways, a radical proposition. The average American could build and safely fly their own aircraft.

Milwaukee’s connection to the homebuilt movement didn’t fade with the relocation of EAA events. Throughout the 1970s and into the early 1980s, the city remained a hub for regional EAA chapters, with active groups in Waukesha, West Bend, and even along Milwaukee’s south side. These chapters acted as both support networks and incubators, where newcomers could learn the basics of aircraft construction and seasoned builders could troubleshoot advanced aerodynamic problems over coffee and sheet metal.

One of the most vibrant of these chapters operated out of a hangar at Timmerman Field, the very site of the original 1953 fly-in. The location’s historical weight was not lost on its members. In fact, some of the original attendees returned as mentors and instructors, helping a new generation take to the skies.

By the late 1970s, several Milwaukee-area high schools had even introduced extracurricular programs linked to local EAA chapters, blending STEM education with hands-on experience in woodworking, electrical systems, and aircraft mechanics.

The local aviation community, too, never severed its ties to EAA. Milwaukee’s General Mitchell International Airport, primarily a commercial facility, routinely supported EAA flyover demonstrations and vintage aircraft transits during AirVenture week, acting as a refueling or staging site for cross-country pilots.

Pilots from Milwaukee often volunteered with logistics or shuttled aircraft back and forth during the Oshkosh gathering, maintaining an informal pipeline between the two cities. Even cultural events bore the mark of EAA’s Milwaukee origins.

When the Milwaukee Air & Water Show was revived in the early 2000s after years of dormancy, several of its organizers had ties to EAA chapters or had participated in earlier iterations of the Milwaukee Air Pageant. Though the revived show emphasized military aerobatics and lakeside spectacle, its lineage ran straight through the civic aviation culture that helped birth EAA a half-century earlier.

For all its national and global reach, EAA’s identity remains tethered to that Milwaukee ethos. It is an ethic of DIY invention, communal problem-solving, and blue-collar brilliance. Now headquartered in Oshkosh, with a sprawling campus and world-class aviation museum, EAA has grown into an institution.

But its archives still house hundreds of original documents, letters, and schematics from the Hales Corners days. Many of the earliest artifacts, including Poberezny’s hand-drawn membership cards, were sourced directly from Milwaukee-area garages, attics, and personal collections.

The continuity isn’t just archival. Several contemporary EAA leaders and chapter presidents still hail from southeastern Wisconsin. Some are second-generation or even third-generation members, inheriting both tools and traditions. They cite Milwaukee’s experimental aviation legacy as not just historical background, but a living influence on how the association functions today.

Enthusiasts and historians alike have pointed to Milwaukee’s durable aviation subculture as one rooted in practicality and quiet innovation. The idea that anyone with time, skill, and determination could build a flyable aircraft resonated deeply in a city defined by its manufacturing base and self-reliant communities.

That generational bridge may be EAA’s most enduring Milwaukee legacy. It is a belief passed down by mentorship and method. Today, Milwaukee-area EAA chapters continue to operate as active hubs within the national network, hosting technical workshops, FAA forums, and builder meetups throughout the year.

Events held at Timmerman Airport and surrounding hangars draw attendees from across southeastern Wisconsin, underscoring the region’s enduring role as a hands-on laboratory for experimental flight.

In a field where most national organizations quickly outgrow their founding cities, EAA remains an outlier. Its world headquarters may lie in Oshkosh, and its event calendar may span the globe, but its roots, firmly and enduringly, remain planted in Milwaukee’s soil.

Special thanks to the medical volunteers at the First Aid Station on Schaick Avenue for their care and treatment of photojournalist Lee Matz during EAA AirVenture Oshkosh 2025. In his enthusiasm to visually document the event, he became dangerously dehydrated. Their kindness and compassion is much appreciated.

Lee Matz