Milwaukee native Cristina Costantini’s award-winning film kicked off the 2018 Milwaukee Film Festival as its opening night feature presentation on October 18 at the Oriental, the same theater she grew up watching movies at while, as a student, Costantini herself competed in science fairs.

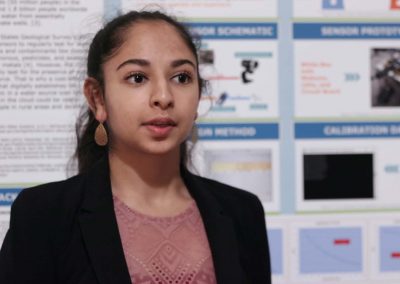

The National Geographic documentary and Sundance Festival Favorite is an account of America’s annual International Science and Engineering Fair (ISEF), a gigantic competition open to high-school science students from all over the globe. At the annual final in Los Angeles, 1,700 young people must present their projects in trade-fair style booths and be prepared to answer questions from judges. The film follows a handful of these idealistic young minds who are outspoken and smart, and who sees an opportunity to gain entry into the best colleges by winning the competition.

“Science Fair is a love letter to the subculture that saved me. As a dweeby kid growing up in a sports-obsessed high school in Wisconsin, the international science fair became my lifeboat,” said Costantini. “It validated my passion for science, taught me how to dedicate myself to a goal and set my life on a trajectory that would have otherwise been totally impossible. But most important, science fair is where I found my tribe.”

For many young and brilliant teenagers around the world, having the chance to compete at the annual ISEF is a dream come true. It is the ultimate opportunity to showcase their innovative projects and demonstrate how they intend to make a difference in their communities through scientific discovery.

This audio was recorded live after the film’s screening at the Milwaukee Film Festival, with co-directors Cristina Costantini and Darren Foster answer questions from members of the audience.

About

Costantini is an Emmy-nominated reporter and producer. She won an Alfred I. duPont-Columbia University Award for her documentary Death by Fentanyl. She attended Yale University and has reported for the New Haven Independent, ABC News, Univision, The Huffington Post, and Fusion.

Q&A with Cristina Costantini

In high school, how did you get involved with the International Science and Engineering Fair, and what was the competition like?

When I was 14, I went to a school like most American schools that really celebrated sports. I’m not athletic and I have never been very cool. Science fair was where I felt like I’d finally found my tribe. It was kind of an escape from the typical Midwestern high school experience that I was having. I got involved as kind of a fluke. I heard there was a science fair, a lot of kids were doing it, and I designed a project about social conformity, largely inspired by the fact that I did not fit in. It ended up doing very well. I won my state’s high school fair my freshman year. I had no idea that there was another level of science fair, so I found out [when] I won first place that I was going to this thing called ISEF. When I got there, it was incredibly life-changing for me. It opened up my world and introduced me to all different kinds of people from 70 countries around the world. It also validated my intelligence as a young woman and taught me a sense of confidence that I didn’t have before that. So it was incredibly transformative for me and made me the person I am now.

What was the lasting impact from that experience?

While I’m not still in the sciences, the lessons that I learned doing science fair are still applicable to a lot that I do. Science is all about learning how to fail — learning it doesn’t always work out the first time and you need persistence and dedication. And you have to know how to sell your project. So there are all these things that I still use.

What kind of support did you get from your school or community when you were participating in the science fair?

I went to a very good science school, but I was doing a social science [project], so I largely worked alone on the project. But culturally it was not cool then to be a science fair nerd. I very much felt like I was culturally on my own — and I actually liked that, working outside of what other high schoolers were doing at the time. So to say that my high school was not supportive of science wouldn’t be fair, but I definitely was not as celebrated as the football team or the hockey team.

Were there any compelling moments from your involvement in ISEF that inspired you to create the documentary?

Well, I found myself a lot in college telling funny stories to my friends about the things that happened to me at science fair. That impulse to share this world with people has been with me for a long time. One [story] in particular happened on prom night. I was invited by a junior boy, and I was really excited to go, but it coincided with the international science fair. And, just as fate would have it, on the very night of my prom, there was also a science fair dance. So instead of with my crush, I was with 2,000 science fair nerds. I remember a kid came up to me, and he had a glass of water and some kind of measuring device. He was measuring the amplitude of the waves in the water to figure out what the decibel level of the speakers were. Those kinds of things happened a lot at the science fair. It was like 2,000 brilliant kids who are not scared to share their minds with other kids.

Why was it important for you to feature the perspectives of nine different students in the documentary?

I really wanted to capture the diversity of the science fair as I remembered it. I wanted there to be underdogs and longshots, kids who are coming from a setting that were not supportive of science or not well-resourced. One of those kids is Kashfia from South Dakota. She’s the only Muslim girl in her high school, and she couldn’t find anybody to support her science fair project at her school — none of the science teachers have the time or want to help. So she ends up in this very unlikely friendship with the head football coach. Coach Schmidt has no clue about science, but he’s really supportive. That relationship was really compelling because here’s somebody who doesn’t know a single thing about science, but he has the right approach to supporting students and fostering their interests.

Then on the other end is a team that we followed from Jericho High School in Long Island. Dr. McCalla has the most winning science fair team in the world, and she’s one of the best — if not the best — teacher I’ve ever witnessed in action. She’s incredible. She runs her science fair team like a football team. She’s like a drill sergeant. She has this team that’s made up completely of immigrants and the children of immigrants. They’re brilliant and really exciting to watch because their school really pours resources into science fair, which you don’t see in most parts of the country. We also have international students, [including] a student from Germany and students from the interior of Brazil.

What are some of the projects that the students have completed?

Kashfia has a behavioral project — she’s studying people in large part to understand her school environment. The Brazilians are tackling questions related to the Zika virus, which is very personal to them because they live in the region of Brazil that was hardest hit by Zika and microcephaly. Robbie is this brilliant, quirky kid out in West Virginia doing machine learning. Then there are these kids from Louisville, Kentucky: Anjali is like the most confident, most capable 14-year-old I’ve ever met in my life. She created an ingenious device to measure arsenic in water very cheaply, so it can be replicated easily. There’s really a range.

In the say way that science had these life-changing implications for you, what does it mean to these students?

For many of these kids, it was their lifeboat. For Myllena and Gabriel [of Brazil], it was their way out of this poor town they grew up in. For Kashfia, it was the only time of the year that she got to talk with people who shared her interest and also didn’t judge her for what she looked like. She is one of the only people who wears a hijab in her town, which can be very difficult for her. Robbie from West Virginia was failing out of math when we met him, but he had made it to the science fair with a project on number theory. Science fair was the one place where his real passions were validated. He didn’t quite fit into the traditional school system and science fair supported his individual interests.

It meant different things for different kids, but for all of them I think it’s been totally life-changing. I read an interview that you did that mentioned how Robbie’s math teacher didn’t want to talk about number theory with him. Exactly. That, to me, is totally crazy. I think we should be supporting kids who have interest in academic fields. Like Dr. McCalla, if she doesn’t know about something that one of her students is interested in, she’ll go home and read all the journals that she can find related to that topic in order to better support them and encourage those interests. She’s really a model of how to teach.

With initiatives to get girls involved studies for STEM fields, why do you think it is important for young women to have experiences like ISEF?

For me, it was the first time that I was validated for my opinions and for my mind. It’s important for all young kids to feel empowered in a way that ISEF makes kids feel empowered, but especially for young women. It gave me the confidence to do other things that maybe I wouldn’t have had otherwise. I see it in all the young women who compete. I think it changes them, it changes how they see themselves and what they’re capable of. So I think the more that we can have these different programs that reinforce women the better.

Why should the community should support STEM education, and what are the benefits?

Everything about our lives is touched by science. The best things in our lives came about because of science and technology. They make everybody’s lives better every day. And so questioning the value of science at all is mind-boggling to me. The phones that you use, the computers that we use, the cars that you’re driving, the medicine that you’re taking, that was all made because of scientific advancements. It’s everywhere around us, so it’s crazy to me that it’s not always appreciated.

How can educators and institutions better expand STEM education?

I think one part of it is definitely financial. Science fairs are losing their funding. The Siemens competition just ended, Intel pulled their funding [for ISEF after 2019], the Oklahoma state science fair just lost their funding. I think just making sure that these programs continue and that kids from all different backgrounds are encouraged to participate. That’s one thing. On the other side of things, I do think scientists have a PR problem. We need to get better at telling the stories of scientists — why they matter and how they affect everybody’s lives.

What kind of help do you think students are looking for most with their education?

Definitely for the kids like Kashfia and Robbie, they just wish they had somebody who could support their interests and who could encourage them to not just study to get a great SAT score, but to really, foster their individual curiosities. I think that is one of the best things we can do for our students.

© Link

Interview segment written by World Learning and previously published as ‘Science Fair’ Director Cristina Costantini on Why Science Education Matters

- No Studios: A first look inside the downtown hub for creative arts in Milwaukee

- No Studios formally launches with new tenants and membership program

- THUG LIFE: Milwaukee director’s film shows the hate we give to little kids F*cks us all

- The Hate U Give: Advocacy and Empowerment Program using art comes to Milwaukee

- VIP guest list announced for Milwaukee Film’s 10th Annual Festival

- UW-Milwaukee named as one of the best film schools in America

- “Science Fair” to kick off opening night of 10th Annual Milwaukee Film Festival

- “Sijan” and Chip Duncan’s “The First Patient” among world premieres at Milwaukee Film Festival

- Milwaukee stars as final destination in new Mad Max style post-apocalyptic film

- A Weapon of Mass Compassion: Netflix streams film with Milwaukee activists working to end hate

- John Ridley to write and direct film based on his superhero comic “The American Way”

- John Ridley’s comic book sequel continues journey of black hero in alternate timeline

- John Ridley’s Milwaukee movie studio makes “NO” the new “Yes”

- Academy Award winner John Ridley talks movies, Milwaukee, and diversity

- Milwaukee Film welcomes Oscar winner Ridley to Festival board

- Brad Lichtenstein: Documentary Filmmaking as a force for social change

- Formation of film cluster could make Milwaukee a cinematic star

- Milwaukee native’s “Science Fair” wins inaugural award as favorite of Sundance Film Festival

- Milwaukee Film now accepting entries for 2018 Festival

- Milwaukee Film announces 10th anniversary festival dates

- Lynn Novick: A discussion about her Vietnam War film on Veterans Day

- Milwaukee Film Festival 2017 awards $140K in prizes

- Photo Essay: Milwaukee Film Festival’s 2017 Opening Night

- Karen Braam Nook: A decade of volunteerism for Milwaukee Film

- Film festival’s spotlight presentations to feature laughter, inspiration, and cocktails

- MKE Film’s Cream City Cinema lineup to include IshDARR music video

- MKE Film to screen John Ridley’s “Let It Fall” in Black Lens lineup

- Milwaukee’s John Ridley directs upcoming Rodney King documentary

- Oriental Theatre takes center stage for Milwaukee Film expansion

- Milwaukee Film gets historic $2M gift from County Executive Chris Abele

- Milwaukee Film Festival calls for 2017 Entries

- Jacqueline Olive: Filmmaking when racial tеrrоrism is always in season

- Filmmaker Chip Duncan reflects on his study of the world

- More than $300K awarded during Milwaukee Film Fest 2016

- Journey by local veterans inspires hope and healing at Milwaukee Film Festival

- Tolkien & Lewis film explores myth, truth, and the meaning of life

- Can You Dig This? Black Lens film sparks talk about urban agriculture

- Documentary of cross country trek by two local vets premieres at Film Fest

- Photo Essay: Opening Night at Milwaukee Film Festival

- By the Numbers: 2016 Milwaukee Film Festival

- Black Lens lineup announced for 2016 Milwaukee Film Festival

- Milwaukee Film welcomes Oscar winner Ridley to Festival board

- Milwaukee Film Festival reveals first list of 2016 selections

Lee Matz