Medical Mission to Jordan: After more than a decade of Civil War in Syria, and continuing conflicts like the unprovoked Russian invasion of Ukraine that further displaced millions of civilians, understanding the longterm conditions that war refugees face remains relevant. But as public attention fades, such topics do not capture headlines today, even as the impact continues to be felt here in Milwaukee. mkeind.com/jordanmedicalmission

During the six day medical mission to Jordan in January 2023, close to 4,300 individuals were provided medical care by Syrian American Medical Society (SAMS) volunteers. Syrian refugees received 60% of those health care services, while almost 40% went to underserved Jordanians.

As a photojournalist for Milwaukee Independent embedded with Milwaukee-based Dr. Waleed Najeeb and a team of medical professionals from Chicago, I took thousands of pictures of the patients and mission volunteers. The routine became familiar, but the environments were not. Each day we were assigned to a new location across Jordan.

SAMS staff processed somewhere between 30 to 80 patients per doctor at each clinic site in places like Za’atari Camp, Salt, Jerash, En Albasha and Marej in Amman, and Basma in Ma’adab. Medical professionals who had previously volunteered on SAMS missions since 2011 remarked on the changes they had seen over the years. Regarding medical needs, the biggest difference was the transition from crisis care to chronic treatment. While the terrible wounds of the war still lingered, they were no longer freshly acquired. Instead, those injuries had been compounded or replaced over the years by a very common enemy … poverty.

For refugees fortunate to live outside camps like Za’atari, existence still remained a daily challenge. Displaced from homes, families, jobs, and the security of life that people in most nations take for granted, Syrians suffer mostly from easily treatable illnesses because they lack access to basic health care – or the ability to afford it.

Respiratory issues like asthma, from squalid living conditions that exposes children to mold on walls, or teeth rotted to almost nothing because of a sugar-heavy diet and lack of dental care, were some of the most basic health conditions that SAMS volunteers provided medical remedies for.

As the Syrian Civil War began its second decade of conflict in 2021, it remains a humanity crisis unlike any other in recent history. For Syrians still living in their country, civilians continue to be subjected to systematic attacks on healthcare and civilian infrastructure. Chief among the targets is the healthcare system, with loss of services, and the attrition of skilled health care workers.

The horrors that occurred in the early years of the Syrian Civil War have been fairly well reported. Global organizations like UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees) that provide humanitarian funding and support continue to document the conditions of refugees in camps and shelters.

But the scattered millions of Syrian refugees outside the camps have received less attention, as the population has assimilated in host nations like Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon and Türkiye, over a generation since the conflict began.

During the medical mission, it was obvious to see that Syrian children had been and remained especially hard hit by the war. Many were born as refugees and never knew their homeland, or an existence of peace and security. Growing up with exposure to violence and trauma meant that a new generation would most certainly grow up with behavioral problems.

Over the six days I spent at the clinics I met so many people, and a large portion of them I could not photograph. I met a little girl who had been barely a year old when she was hit by a rocket. It destroyed her home and left her with facial burns. Eight years later and as many surgeries to reconstruct her face, she is unable to close her eye lids. The little girl sleeps with her eyes open each night, and risks the loss of her vision.

I met a mother and her teen daughter who fled Syria 11 years ago and found safety in Jordan. Because of the lack of windows in her home, or enough sunshine to prevent moisture from becoming a toxic mold, both have developed pulmonary issues in the past two years. At times they each have trouble breathing, which complicates the daughter’s heart problems.

“There are no job opportunities for us here,” the Syrian mother said. “Back home I was a photographer and had a business. Here, I am just trying to make enough to survive with my family.”

She talked about how aid organizations had sent funds and assistance in the early years of the war, but those resources have all but vanished – compared to the increasing need of the displaced population. It echoed what patients told us every day. Jordan had given them a place to be safe and rebuild their lives. But humanitarian organizations needed to offer long term job opportunities so that the refugees could return to productive lives and work.

At the clinic in the ancient trading city of Salt -formally known as As-Salt, derived from the Latin word “saltus” which means “forest,” a young man had developed fibrosis and other pulmonary complications due to COVID-19. His job had been to collect samples at the start of the pandemic for testing, and he became infected in the process. He has suffered from long-COVID illnesses since.

At another clinic location, I met a 79-year old woman who had escaped the bombing in Syria. Her son and his pregnant wife had also been able to flee, and they took refuge at Za’atari Camp. Her son was eventually able to leave the camp and find work. He settled in the ancient city of Jerash, and she lives together with his family. But between what he earns and the support from UNHCR, the family rarely has enough saved to afford her medication. If she has money, she will buy what she can to manage her medical conditions. Sometimes she is able to get samples from pharmaceutical companies, but conditions grow worse because she cannot maintain a regular regiment of treatment.

Or an orphan boy who lived with his elderly grandmother. He lost both parents in the war, and came from Syria as a small child. He grew up on the streets and was disfigured after he was hit by a car. With only his grandmother to care for him, they both struggle with lack of financial support. Refugee aid continues to evaporate, and was never enough to begin with. The boy remains too young to work, and his grandmother is too old. Like many refugees, they remain stuck. They do not want hand-outs to get by, but the war robbed them of all the options they had to be self-sufficient.

And then there was an old couple, still living with the trauma of escaping the war. The wife was afraid to have her photo taken, for fear that the Syrian police could find where she lived in Jordan. Her husband lost an eye when the concussion of an explosion shattered the window glass in their home.

Each photo I took connects to a memory, and they play on a loop in my mind. Like the young couple who brought their baby son to see Dr. Najeeb for a second opinion. His condition was sadly inoperable. The couple had not trusted that same diagnosis by a local doctor. There was nothing Dr. Najeeb could do, but offer them comfort in the painful knowledge. The couple remained just as helpless, but they did not have the anxiety of not knowing. They could use the remaining time to face the very emotional challenges in the weeks ahead.

Many stories were like these, the very old, the very young, all struggling to survive as refugees outside of camps. Working age adults were working, and in the same need of medical care, but unable to take time off to seek attention.

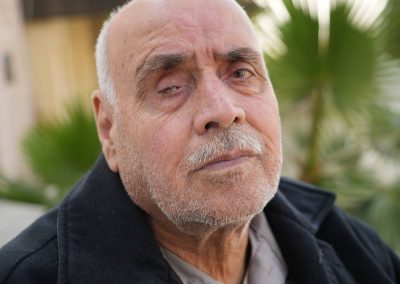

Hospitals have often been characterized as the most dangerous places in Syria. Yet the lack of medical care, anywhere in the world, proves to be one of the most deadly problems. The images in this collection present only a small sample of the Syrian refugees treated by SAMS volunteers. Their faces and stories continue to show the human costs that continue to grow even after so many years of conflict.

This photo collection was taken over six days, from January 21 to 26, at six different locations, which consisted of SAMS clinic locations in Za’atari Camp, Salt, Jerash, En Albasha and Marej in Amman, and Basma in Ma’adab.

Because of privacy issues, a highly secure environment, and limited resources on the ground in Jordan, I was not able to conduct extensive interviews with patients. All of the dozens of people I photographed each day had a heartbreaking story. The worst were usually not some disfiguring war wound, but a mundane health condition that proved debilitating due to lack of treatment.

This editorial feature is one of a multi-part explanatory series about the “Dr. Majdi Omar” SAMS Jordan January 2023 Medical Mission. The journalism project embedded a Milwaukee Independent photojournalist, from January 21 to 26, 2023, with a group of Syrian American doctors from Milwaukee and Chicago. It documented their trip to Jordan and the medical work done at clinic locations like Za’atari Camp, Salt, Jerash, En Albasha and Marej in Amman, and Basma in Ma’adab. Medical Mission to Jordan: A journey from Milwaukee to help Syrian Refugees, shares the personal voices, stories, images, and conditions around those involved in the Syrian American Medical Society (SAMS) mission to Jordan. It also explores the refugee experience, and the intimate connections of local medical professionals, who put their work on hold and left their families behind for a couple weeks to provide healing to others who have endured a generation of trauma.

Series: Medical Mission to Jordan

- Medical Mission to Jordan: Traveling from Milwaukee to document the conditions of displaced Syrians

- Refugees in need: How the Syrian American Medical Society is able to provide vital medical services

- Waleed Najeeb: A spiritual duty to bring specialized relief to those suffering from a decade of war

- Za’atari Refugee Camp: Syrians struggle with a decade of life in the bubble of a temporary shelter

- Jihad Shoshara: How medical advocacy empowers Syrians living with guilt and trauma from a distance

- Deadliest in a decade: Untold numbers remain buried under rubble in Syria after devastating earthquake

- Medical Mission to Jordan: A visual diary from a week with Syrian refugees and SAMS volunteers

- Hazar Jaber: Advocating for oral health so poverty does not make sugar into a poison for children

- Bassel Atassi: Holding onto a family identity after Syria went from a home country to a ghost country

- Medical Mission to Jordan: The faces of Syrian refugees and their health struggles after years of war

- Abrar Qureshi: Finding a "Street of Happiness" among the faded ruins of hope in Za’atari

- Abdullah Chahin: Building a collective purpose to provide medical care as a Syrian in exile

- Zein Barakat: A spirit of volunteerism that nurtures an abundance of compassion, love, and humility

- Hima Humeda: A Syrian college student’s story from childhood heart surgeries to caring for war refugees

- A clarity of vision: Giving displaced Syrian children the ability to see a world full of possibilities

The 7.8 magnitude earthquake struck parts of Syria and Türkiye on February 7. It came a week after the SAMS Medical Mission ended, and while Milwaukee Independent finished the final production of this editorial series. The public is encouraged to make donations to the Syrian American Medical Society in support of their vital crisis relief work.

Lее Mаtz

Omar Abdulla Bataineh

Lее Mаtz