Medical Mission to Jordan: After more than a decade of Civil War in Syria, and continuing conflicts like the unprovoked Russian invasion of Ukraine that further displaced millions of civilians, understanding the longterm conditions that war refugees face remains relevant. But as public attention fades, such topics do not capture headlines today, even as the impact continues to be felt here in Milwaukee. mkeind.com/jordanmedicalmission

Medical professionals spend many years learning, growing, and accomplishing work in their field. For those who were not born in the United States, or are from immigrant families, the path to medical school is often an adventure story in itself. In preparing introductions of the Syrian American Medical Society (SAMS) volunteers who were interviewed for the “Medical Mission to Jordan” series, the depth of what each individual has achieved in their career literally requires a separate article to detail. Being chief of a department, or professor, or research leader, or board chair, are all in addition to the root vocation of their dedicated medical care of adults and pediatric patients. In this context, regardless of position or occupation, all the volunteers of the SAMS Medical Mission arrived in Amman with one purpose, to offer crisis relief to refugees affected by the Syrian Civil War. Exploration of medical backgrounds was explained within each interview to the extent necessary by the participant. While each layer of their medical career and position of responsibility were essential to their mission work in Jordan, those detailed descriptions were actually a distraction in being able to share their story. Who they were “in person” was why they were interviewed. Not who they were “on paper,” which was still immensely impressive but simply too much to unpack in this context.

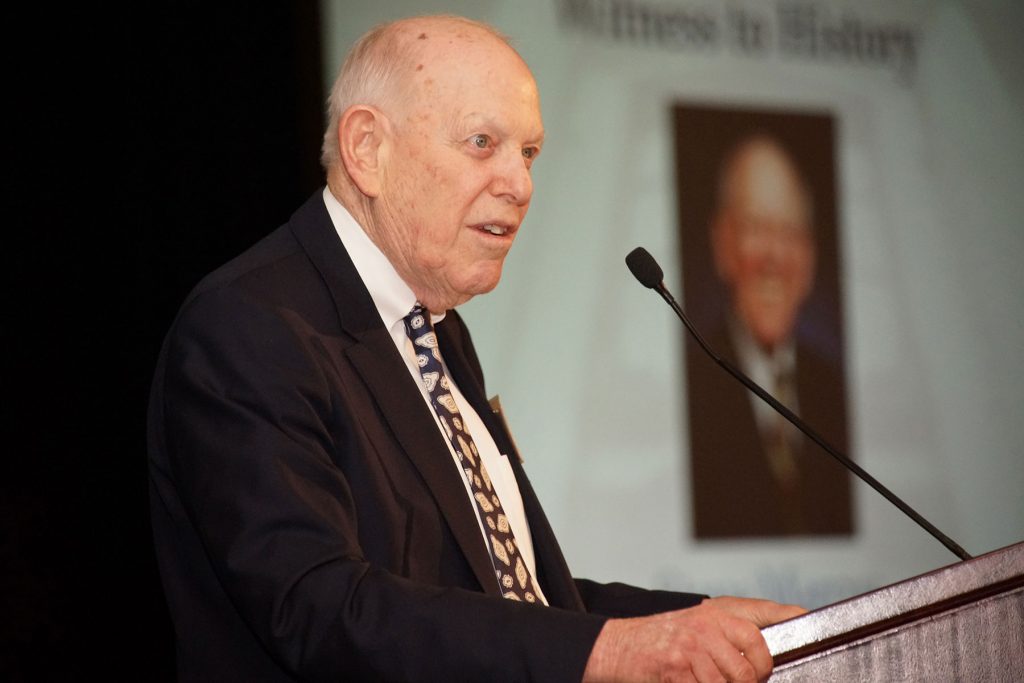

Q&A with Dr. Abdullah Chahin, MD

Milwaukee Independent: How were you inspired to follow a career in the medical field?

Abdullah Chahin: There is what you would aspire to when you are 16, and there is where reality takes you to when you are 16. My dream would have been to pursue mathematics and philosophy. But eventually as someone from a struggling expatriate Arab middle class family who tried to secure a safe future, medicine was the second best thing I could do. So it was not necessarily the career that I dreamed of as a child, but something that I took from the options that were laid out for me on the table. I was lucky to actually choose this field, because it is certainly something that is very unique.

Milwaukee Independent: What do you enjoy most about the medical field and being a doctor?

Abdullah Chahin: There is no other job where people who come for their job, speak of nothing but their job. And if you ever sit with a group of physicians, all we talk about is our job just because it is fascinating. It is touching the lives of people at the very deepest level. And you still feel that you are benevolent, and that you are doing something that is good – you are doing it because you want to do good. And luckily, we are able to do that still. For most of us – regardless of money, or payment, or any kind of financial rewards – we continue to feel it. We are doing the work to actually help people, and nothing else.

Milwaukee Independent: Where were you when you heard about the Civil War in Syria, and how did that initially impact your life?

Abdullah Chahin: Let me get sidetracked a little bit. In 2008 I was writing for Wikipedia, and there was a Wikimedia conference in Egypt. So we went to Alexandria, and I had the stereotypical picture in my mind of what the typical style of living was like in the Gulf area. Low paying jobs, and not the best educated folks. People who were kind of submissive and not confrontational. I had an unflattering picture of Egyptians in my head because of the unconscious bias that my environment had created. So I got there with all these preconceptions, and then I met very intellectual polyglots from the upper middle class. These young Egyptians were doing amazing things. It was before the Arab Spring, and I was in this country with a huge heritage taking long walks in the streets of Cairo. But then I encountered an extreme amount of poverty. At the conference, I remember there was a picture of Suzanne Mubarak, who was the wife of the president, at an opening ceremony. What struck me was the corruption that seemed to emanate out of the image. I said to myself, a revolution here is past due. After the conference, I went back to my country, and I realized that everything was the same in Syrian society. But I just did not have enough faith in my own people. I did not think they would actually be able to do something collectively or inspiring or dangerous or as history changing as the Syrian Revolution. I honestly believed that it would never happen in Syria. It would never happen at that scale in Syria. But it only took three years to prove me wrong. I was in the United States in 2010, and had left Syria a year before – knowing that I would never go. I had already been arrested and interrogated for doing nothing like so many others. At that time, a million Syrians were internally displaced because of the droughts, and the disastrous government policies for agricultural loans. I helped launch a campaign to supply sleeping bags for homeless people, and give packages of crayons and candy to children. Because of that charity, it was considered an insult to the image of the country, And, I was accused of conspiring with the West. So I came very close to being another prisoner who just disappeared. Luckily I was able to escape, but knew I could never go back. That was just 13 months before the revolution started.

Milwaukee Independent: Do you still have connections in Syria, and what has been the impact on them since you left?

Abdullah Chahin: A lot of my family who I left behind, and called Syria home, they no longer live there. Almost everyone that I know from my childhood, either as family or as a friend, are now living outside of Syria. They are spread out over four different continents. I believe Syria was on the trajectory that it was going regardless. I just thought it would take a different route and not be so devastating. Believe it or not, it actually gave me a sense of belonging to a society that I never really felt when I was there. I finally felt a strong connection to my country, even though it was lost to me. Before the war, Syria was symbolized by the father figure that we had as a dictator. It was his country, and Syrians were not a part of it. We had no central identity. It was like we lived under a big flying saucer called Syria. We were just hanging from underneath it. The only thing we seemed to share, or have in common, was that we were all stuck in the shadow of that big flying saucer.

Milwaukee Independent: How did you become involved with the Syrian American Medical Society (SAMS)?

Abdullah Chahin: Before the revolution started, it felt like we were all individuals. We really did not believe in a collective purpose in Syria. We did not even have the courage to trust each other. I knew Bassel Atassi, a SAMS mission leader, from medical school. He is also a relative, but I would never speak about politics with him, or trust that we would be on the same page. So it took time for us to evolve into some smaller communities and organizations. In the beginning, I was working with a few folks that I met. They lived much further away but we shared social network connections. It was the cause that actually brought us together. Eventually, we became geographically closer and started working together. We partnered on tele-health and other projects to provide health care aid in Syria. But then I saw there was a lot of duplication of effort, and it would be better to not reinvent the wheel. So I focused my efforts into one channel and that was SAMS.

Milwaukee Independent: What has been your experience with medical missions for Syrian refugees, from the initial tragedy to the state of complacency now?

Abdullah Chahin: Aside from medical relief efforts by Canada, it was not until very recently – maybe two or three years ago – that there was nothing other than trying to stop the bleeding. There was nothing in place to actually try and save lives. Because there was an active state of war, there was no capacity for any other kind of care but treating casualties. When conditions settled down, then we started focusing on the millions left homeless and what kind of society that would create for decades to come. We started thinking about how to get them vaccines and access to primary health care. That transition took us at least five or six years, before we started thinking about how to help people after there was no immediate danger of war. What can we do for these millions of people, the masses who actually ended up being completely ignored – because we only focused on the low hanging fruit. So we put together programs for basic medicine, and vaccines, and then started a cancer treatment center. It was something that defied all the logic behind how NGOs did their calculations. It was a numbers game to them, they wanted to spend $10,000 and have 10,000 impacts. But we wanted to spend $10,000 to help one patient who needed complex care. It showed the other aid groups that a single human life mattered. That philosophy is still really unique.

Milwaukee Independent: What were you surprised to learn about yourself after your first SAMS mission?

Abdullah Chahin: I came here trying to be a provider, and to also see what I can do without necessarily being the provider – in terms of systems building. The mission helped me think about how I can be more efficient with my time to help people, to have more impact. Not just being impactful in the numbers but in the quality of care. I am in Jordan for a week every six months, and I think about what can be done in the time that I am not here. I see the state of poverty, and I think about how can people afford medication. It is more expensive than school supplies or food for an entire month. It haunts me, and pushes me to ask hard questions of myself. When I am not here, what can I do? What role can I have outside this country that has the same impact as if I continued being here?

Milwaukee Independent: What was the hardest experience of your working with Syrian refugees?

Abdullah Chahin: You always have this urge to help, and to help to the maximum that you can do. But at the same time, you cannot actually carry the whole entire world. You realize how insignificant you are as an individual. We are reminded of this every single day. No matter how much suffering I see, there is only so much I can do to ease it. There is a limit to what I can accomplish on my own. But it also inspires me to be a part of a larger collective. A group has more of an awareness and bigger budgets and can just accomplish more. So there is humility and despair, but also encouragement to do something in a different way.

Milwaukee Independent: What would you like the public to know about conditions in refugee camps?

Abdullah Chahin: People do not naturally care, we are not designed to care for things that we do not see. Whether it is climate change, whether it is a Syrian refugee camp thousands of miles away from Chicago. I think our job is to actually try to care in a different way where we are. We have the sense that we have to treat things equal, but they are not. And sometimes, that is the key for making a difference. There are a lot of sad stories of people who suffer. But there are only two or three stories that can actually have an impact, that will be written up in a nice New York Times article. It is not an issue of advertising the work we do. But it is necessary to focus the scope of the issue through the lens of selected sufferings. People cannot connect with thousands of stories of trauma, but they can connect with a few. We can connect with another human being when it becomes personal, and not just numbers. So I do not think that people need to direct their support from their own pockets. But I think collectively, in any wealthy country where budgets are managed in trillions of dollars, to create a very small and steady stream to make sure that basic human needs are taken care of. We are calling the right to healthcare a human right. There is not enough support for that, and I think it is something we need to fix.

Milwaukee Independent: Where do you still find hope?

Abdullah Chahin: We are a very resilient species. Even with the level of poverty that we see here, there are still children goofing around and playing. These are not inanimate objects, these are little people full of life, who will go on to write their own stories regardless of us being around to help them or not. I wish people could understand and appreciate the need and the right of Syrian culture to exist. There is happiness outside of the stereotypical images of suffering that people see.

This editorial feature is one of a multi-part explanatory series about the “Dr. Majdi Omar” SAMS Jordan January 2023 Medical Mission. The journalism project embedded a Milwaukee Independent photojournalist, from January 21 to 26, 2023, with a group of Syrian American doctors from Milwaukee and Chicago. It documented their trip to Jordan and the medical work done at clinic locations like Za’atari Camp, Salt, Jerash, En Albasha and Marej in Amman, and Basma in Ma’adab. Medical Mission to Jordan: A journey from Milwaukee to help Syrian Refugees, shares the personal voices, stories, images, and conditions around those involved in the Syrian American Medical Society (SAMS) mission to Jordan. It also explores the refugee experience, and the intimate connections of local medical professionals, who put their work on hold and left their families behind for a couple weeks to provide healing to others who have endured a generation of trauma.

Series: Medical Mission to Jordan

- Medical Mission to Jordan: Traveling from Milwaukee to document the conditions of displaced Syrians

- Refugees in need: How the Syrian American Medical Society is able to provide vital medical services

- Waleed Najeeb: A spiritual duty to bring specialized relief to those suffering from a decade of war

- Za’atari Refugee Camp: Syrians struggle with a decade of life in the bubble of a temporary shelter

- Jihad Shoshara: How medical advocacy empowers Syrians living with guilt and trauma from a distance

- Deadliest in a decade: Untold numbers remain buried under rubble in Syria after devastating earthquake

- Medical Mission to Jordan: A visual diary from a week with Syrian refugees and SAMS volunteers

- Hazar Jaber: Advocating for oral health so poverty does not make sugar into a poison for children

- Bassel Atassi: Holding onto a family identity after Syria went from a home country to a ghost country

- Medical Mission to Jordan: The faces of Syrian refugees and their health struggles after years of war

- Abrar Qureshi: Finding a "Street of Happiness" among the faded ruins of hope in Za’atari

- Abdullah Chahin: Building a collective purpose to provide medical care as a Syrian in exile

- Zein Barakat: A spirit of volunteerism that nurtures an abundance of compassion, love, and humility

- Hima Humeda: A Syrian college student’s story from childhood heart surgeries to caring for war refugees

- A clarity of vision: Giving displaced Syrian children the ability to see a world full of possibilities

The 7.8 magnitude earthquake struck parts of Syria and Türkiye on February 7. It came a week after the SAMS Medical Mission ended, and while Milwaukee Independent finished the final production of this editorial series. The public is encouraged to make donations to the Syrian American Medical Society in support of their vital crisis relief work.

Lее Mаtz

Lее Mаtz