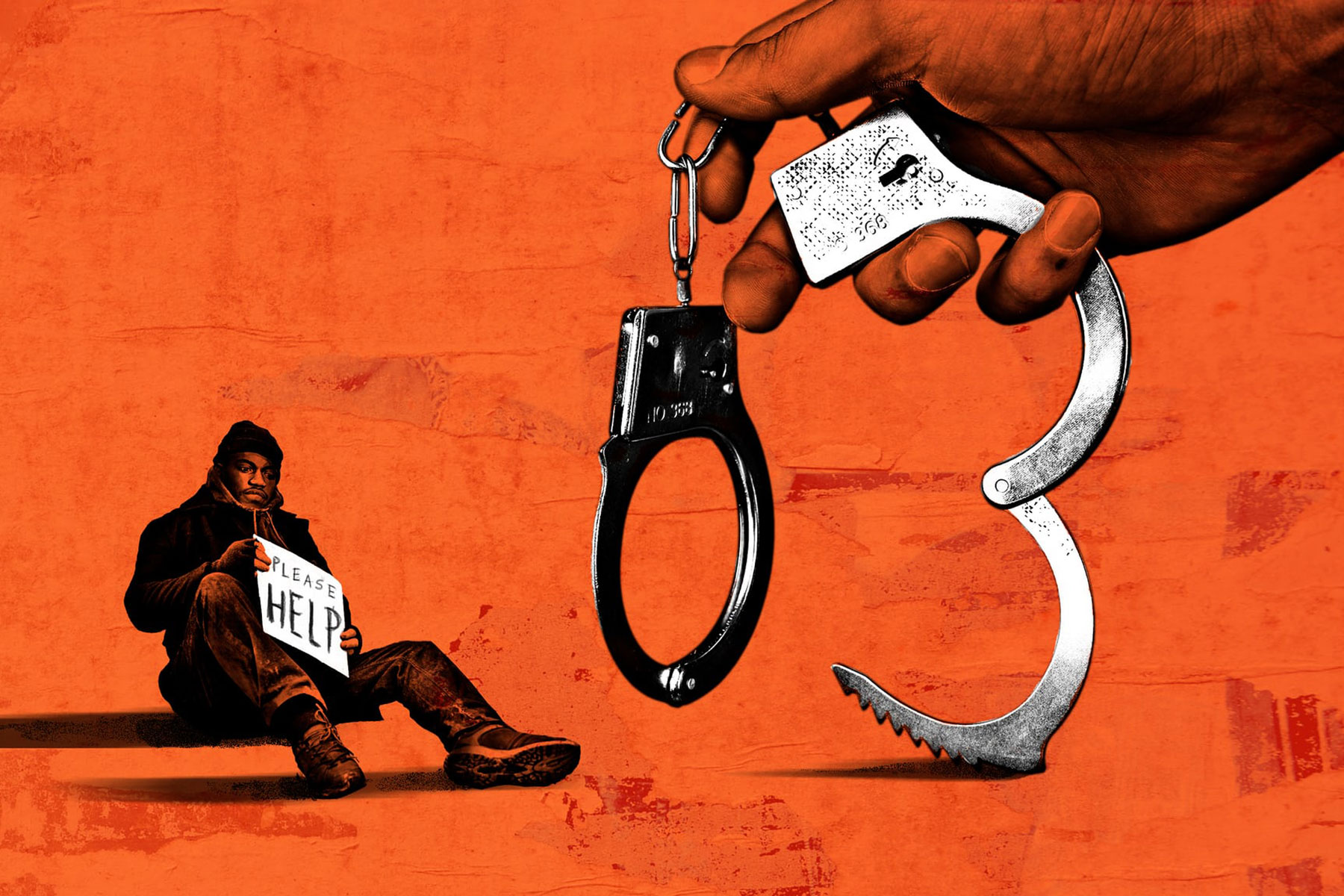

In the United States, a system of modern peonage – essentially, a government-run loan shark operation – has been going on for years.

Beginning in the 1990s, the country adopted a set of criminal justice strategies that punish poor people for their poverty. Right now in America, 10 million people, representing two-thirds of all current and former offenders in the country, owe governments a total of $50bn in accumulated fines, fees and other impositions.

The problem of “high fines and misdemeanors” exists across many parts of the country: throughout much of the south; in states ranging from Washington to Oklahoma to Colorado; and of course in Ferguson, Missouri, where, in the wake of the killing of Michael Brown, revelations about the systematic criminalization of the city’s poor black residents brought these issues to national attention.

As a result, poor people lose their liberty and often lose their jobs, are frequently barred from a host of public benefits, may lose custody of their children, and may even lose their right to vote. Immigrants, even some with green cards, can be subject to deportation. Once incarcerated, impoverished inmates with no access to paid work are often charged for their room and board. Many debtors will carry debts to their deaths, hounded by bill collectors and new prosecutions.

Mass incarceration, which has disproportionately victimized people of color from its beginning in the 1970s, set the scene for this criminalization of poverty. But to understand America’s new impulse to make being poor a crime, one has to follow the trail of tax cuts that began in the Reagan era, which created revenue gaps all over the country.

The anti-tax lobby told voters they would get something for nothing: the state or municipality would tighten its belt a little, it would collect big money from low-level offenders, and everything would be fine.

Deep budget cuts ensued, and the onus of paying for our justice system – from courts to law enforcement agencies and even other arms of government – began to shift to the “users” of the courts, including those least equipped to pay.

Exorbitant fines and fees designed to make up for revenue shortfalls are now a staple throughout most of the country. Meanwhile, white-collar criminals get slaps on the wrist for financial crimes that ruin millions of lives. Though wealthy scofflaws owe a cumulative $450bn in back taxes, fines and fees from the justice system hit lower-income people – especially people of color – the hardest.

“Broken windows” law enforcement policy – the idea that mass arrests for minor offenses promote community order – aided and abetted this new criminalization of poverty, making the police complicit in the victimization of the poor. Community policing turned into community fleecing. Enforcing “quality of life” rules was touted as a way to achieve civic tranquility and prevent more serious crime. What it actually did was fill jails with poor people, especially because those arrested could not pay for bail.

Budget cuts and the new criminalization have inflicted other cruelties as well. Under “chronic nuisance” ordinances created by underfunded police departments, women in some poor communities can be evicted for calling 911 too often to seek protection from domestic abuse.

Public school children, particularly in poor communities of color, are arrested and sent to juvenile and even adult courts for behavior that not long ago was handled with a reprimand. The use of law enforcement both to criminalize homelessness and to drive the homeless entirely out of cities is increasing, as municipalities enact ever more punitive measures due to shortages of funds for housing and other services.

In addition, low-income people are deterred from seeking public benefits by threats of sanctions for made-up allegations of benefits fraud. As elected officials have moved to the right, laws designed to keep people from seeking assistance have grown more common. Budget cuts have also led to the further deterioration of mental health and addiction treatment services, making the police the first responders and jails and prisons the de facto mental hospitals, again with a special impact on minorities and low-income people.

Racism is America’s original sin, and it is present in all of these areas of criminalization, whether through out-and-out discrimination, structural and institutional racism, or implicit bias. Joined together, poverty and racism have created a toxic mixture that mocks our democratic rhetoric of equal opportunity and equal protection under the law.

A movement to fight back is showing signs of developing. Organizers and some public officials are attacking mass incarceration, lawyers are challenging the constitutionality of debtors’ prisons and money bail, judicial leaders are calling for fair fines and fees, policy advocates are seeking repeal of destructive laws, more judges and local officials are applying the law justly, and journalists are covering all of it.

The Obama administration’s Department of Justice stepped into the fray on a number of fronts. Ferguson was a spark that turned isolated instances of activism into a national conversation and produced numerous examples of partnerships between advocates and decision-makers.

Now we must turn all of that into a movement. The ultimate goal, of course, is the end of poverty itself. But as we pursue that goal, we must get rid of the laws and practices that unjustly incarcerate and otherwise damage the lives of millions who can’t fight back. We must fight mass incarceration and criminalization of poverty in every place where they exist, and fight poverty, too.

We must organize – in neighborhoods and communities, in cities and states, and nationally. And we must empower people to advocate for themselves as the most fundamental tool for change.

- Copyright © 2017 by Peter Edelman. This excerpt originally appeared in Not a Crime to Be Poor: The Criminalization of Poverty in America by Peter Edelman, published by The New Press. Reprinted here with permission.

- Peter Edelman is the Carmack Waterhouse Professor of Law and Public Policy at Georgetown University Law Center, where he teaches constitutional law and poverty law and is faculty director of the Georgetown Center on Poverty and Inequality

Peter Edelman

Rob Dobi

Originally published by TheGuardian as How it became a crime to be poor in America

Help deliver the independent journalism that the world needs, make a contribution of support to The Guardian.