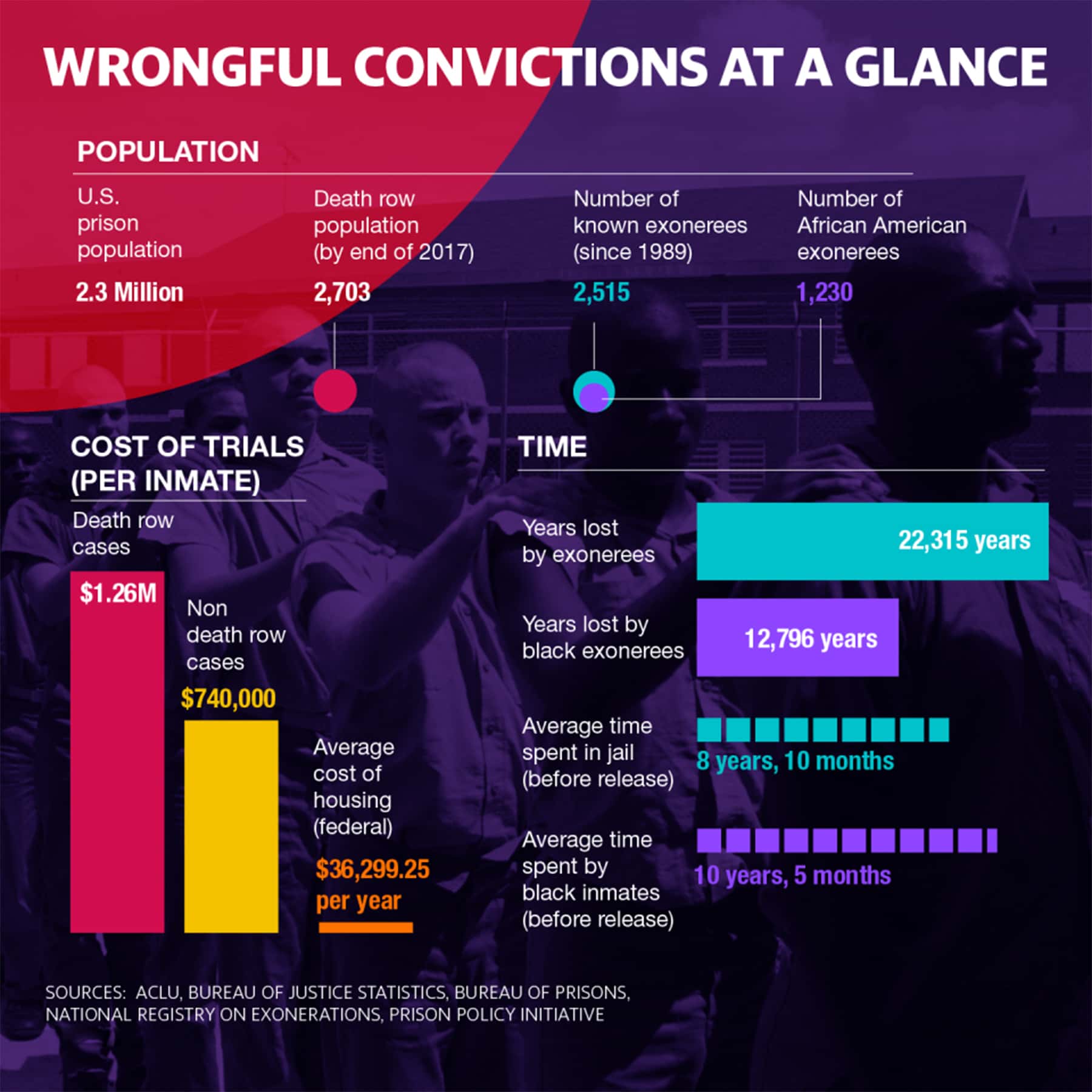

According to the National Registry of Exonerations (NRE), since 1989 the United States has paid hundreds of millions to incarcerate 2,515 men and women who were later exonerated after proving their innocence.

Among all known exonerees, Americans have shelled out a staggering $4.12 billion to incarcerate innocent men and women since 1989. That is largely money spent on trials, and the cost of housing inmates in prison. According to the Bureau of Prisons, in the fiscal year 2017, the average cost to house a prisoner was over $36,000 a year in federal facilities.

But black men make up the majority of those wrongfully convicted — approximately 49%. And since 1989, taxpayers have wasted $944 million to incarcerate black men and women that were later found to be innocent. That number climbs to $1.2 billion when including Hispanic men and women. In 2019 alone, American taxpayers shelled out nearly $79 million for a combined 105 people who were exonerated this year.

On average, from the time a person enters the criminal justice system until they are exonerated, $1.26 million is spent per inmate who is facing the death penalty. In cases where there is no capital punishment charge, the cost drops to $740,000. With 123 exonerated inmates previously on death row, roughly $155 million was spent to incarcerate them. An additional $1.7 billion was spent to incarcerate the remaining 2,392 people that weren’t facing the death sentence. In total, before compensation was factored in, just under $2 billion was spent to imprison innocent people.

“Basically, every stage of the process is more expensive in a capital case,” says Cassy Stubbs, director of the ACLU Capital Punishment Project. “The jury selection is a time-intensive process that gobbles up all the court and attorney time. There are more lawyers, a bigger legal team.”

“There are the additional costs of confinement. Death row is extraordinarily expensive to maintain. Single cells, all the security provisions they put into draconian isolation are all very expensive,” Stubbs said.

Compensating the innocent

The total sum — $4.12 billion spent on all known exonerees — also includes $2.2 billion that taxpayers have paid the innocent in compensation since 1989 for the time they were imprisoned, according to a 2018 NRE study written by George Washington Law Professor Jeffrey Gutman. But while a large sum, only 44% of exonerees have ever received compensation. Of those who did get some form of restitution, the money covered just over 60% of the years lost by exonerees.

Gutman said that the number for both state and civil compensation has gone up since, to $2.47 billion. But the number is not representative of all those that are known exonerees. If all known exonerees did receive compensation, the numbers would quickly balloon.

“The reason it isn’t higher than that is because there are some who don’t seek compensation at all, and those who seek it and are denied,” Gutman said.

Gutman’s NRE study finds that on average, exonerees receive compensation from the state worth $70,000 for each year they were incarcerated, and then $307,000 for each lost year from civil suits. If all 2,515 exonerees received compensation for the years lost, they would be owed anywhere from $1.6 billion to upwards of $7 billion. But housing and litigating against innocent men and women isn’t just the only cost to society. For each wrongfully convicted person, there’s also the years of lost productivity and taxable salaries.

Considering that the average length of incarceration is 8.9 years, the lost salaries of all 2,515 known exonerees in 2019 dollars is roughly $712.2 million, taking into account the median salary of 2004, the median year between 1989 and today. That is more than $700 million that could have been spent paying taxes, investing in the stock market, paying into health insurance, buying consumer products, and supporting their families. Vanessa Potkin, director of Post Conviction Litigation at the Innocence Project, which represents Reed, said these costs are “just the beginning.”

“There is the cost of incarceration — oftentimes that’s decades. What does that mean to a family when a father is not present?… And as a family, availing themselves of basically public assistance to stay afloat because the family structure has been devastated by incarceration,” she said.

The societal costs

But these are just the quantifiable costs. The cost to a person’s family, to their community, and to society at large, said Klara Stephens, a research fellow at the NRE, is not “quantifiable by any measure.”

“The toll on people who have incarcerated loved ones — and this isn’t exclusive to innocence — it’s both an economic cost because that parent can’t be economically productive and provide for that child and can’t provide care and love,” Stephens said. “And with people who are innocent, the difference is the weight of ‘we did everything right, and we are still being punished. The cost of knowing the state is willing to execute people for crimes they didn’t commit looms pretty large and I would say accounts for the declining popularity of the death penalty.”

Potkin agrees, recalling a story of a man who went to prison when his son was only a couple of years old. When he walked out, he had a grandson in his 20s.

“You wonder,” she said, “if the grandfather hadn’t been wrongfully imprisoned where the grandson would be today. Would he have been able to provide? It’s multigenerational, the impact.”

Potkin rattled off the list of other things lost: weddings, funerals, experiences, like being a grandparent. “These are people who could be fathers, grandfathers, who have talents that could be contributing to society instead of caged and making a profit for some. ”

The overrepresentation of black men

And it is black men who disproportionately bear the brunt of loss associated with wrongful convictions. African Americans represent 49% of the known exonerees on the list, despite only making up close to 13.5% of the population in the United States. Whites make up 37% of the list, while Hispanics represent 12% of known exonerees. In addition to being overrepresented in the justice system, black men in particular spend a longer time incarcerated before exoneration — 10.7 years lost, compared to 8 years for white men.

“It’s very clear racism plays a huge role,” said Stephens. “In death sentences alone, and death sentences for people who were later exonerated.”

She noted that while black and white people use drugs at the same rate, black people are 12 times more likely to be wrongfully convicted for drug possession than white people.

“Murder exonerations with black defendants are more likely to have police misconduct,” she added. “And black exonerees are more likely to spend more time in prison than white exonerees.”

Stephens speculated that over-policing of minority neighborhoods might play a role. She said that a risk factor to being wrongfully convicted is having been in the criminal justice system before.

But, she added, “in already over-policed communities, that risk factor obviously goes up. You’re at a higher risk of being wrongfully convicted for a crime just by living in an overly policed community.”

More cases of innocence

While these are the costs associated with the 2,515 known exonerees compiled by the NRE since 1989, it’s unknown how many more innocent men and women are currently incarcerated. According to research published in the National Academy of Sciences, 4.1% of those on death row have been wrongfully convicted. According to a 2019 report from the Bureau of Justice Statistics, by the end of 2017 there were 2,703 inmates sentenced to death. With a wrongful conviction rate of roughly 4%, this means approximately 111 people are currently innocent.

Assessing the wrongful conviction rate for the much larger incarcerated population has been harder to determine. Some estimates are as low as 0.027%, while others are as high as 37.7%. However, most accepted estimates range from 1% to 5%. With some 2.3 million people estimated to currently be incarcerated, that means anywhere from 23,000 to 115,000 people are currently wrongfully imprisoned. Potkin said that the number of people exonerated are “a very small fraction of people in the system.”

“It’s a number that we are never going to be able to ascertain,” Potkin added.

Kristin Myers

Originally published as US taxpayers spent almost $1 billion incarcerating innocent black people