Dear Dr. King,

I wish I’d have written this sooner.

Indeed I should have, but doing so was simply not possible, as it’s taken me this long to realize that these were words that needed to be said — and that they needed to be said by me.

For much of my life I’ve imagined I was fighting the good fight of equality because I believed in it philosophically, because intellectually I agreed it. I’d frequently recited your words and loudly amen-ed your sermons and easily claimed affinity in your declarations of the worth of every human being. I’d have said that I was trying to live as a man after your own courageous heart — but at best I was really play-acting.

Looking back at the path of journey, for far too many of those years I’d actually been one of the white moderates you castigated from a cell in a Birmingham jail: people imagining themselves morally evolved but still afflicted with the latent illness of privilege that resists the messiness of justice — especially when it rattles your blind prejudices and brings turbulence to your places of comfort. As often as I raised my voice to uplift the oppressed, I scolded them when they spoke in ways I deemed too loud, too aggressive, too angry.

In the wake of passionate protests and falling monuments and desperate pleas for equality that spilled over into violence, I too often took a posture of correction, defending some “right way” of protesting, that only reflected the fact that the law and the system never required me to scream to be heard or fight to be considered. I’ve never known that kind of desperation and often mischaracterized it as recklessness, unintentionally quieting the turbulence necessary for justice to come.

Dr. King, I’ve always known you deserved my respect, but it’s only recently that I realized that I owe you an apology.

I’m sorry for the times I stayed silence in the presence of my white friends while they perpetuated caricatures of people of color: when they made the lazy joke or wielded the most dehumanizing stereotypes — and for the times I myself generated the ignorant laughter of my peers, never considering the collateral damage of making human beings into punchlines.

I’m sorry that I assumed myself progressive, while never talking ownership of my privilege or facing my culpability in the systemic racism of this nation; the times I wanted to see myself as one of the good guys, yet wasn’t able or willing to see or confront the ways I have profited from my whiteness since birth.

I’m sorry that I was such a lousy student of History; never stopping to realize that it had largely been written by people who needed to be the heroes even as they perpetuated the villainy.

I’m sorry that I so often spoke in the cause of vulnerable and marginalized people, instead of actually first listening to them — because the former was much easier and the latter more potentially uncomfortable.

I’m sorry that I wanted to proudly wear the bleeding heart badge of being for equality, but didn’t want to enter the jagged, bloody trenches of the white anti-racist; that I wasn’t willing to get my hands dirty and draw the bruises and broken bones that come when bigotry is confronted by its direct counterpoint.

I’m sorry that as a Christian minister, I once participated in a conservative Church that has been an agent of inequity and harborer of white supremacy since its inception — and later in a progressive Christian Church that has grown shamefully silent in days when it should be an audacious prophetic voice condemning the present supremacy.

I’m sorry for assuming that simply because a man of color finally occupied the seat of greatest power in this nation, that we could be less vigilant or passionate in the cause of equality, or that the malignant cancer of racism wasn’t as metastatic as it had ever been. I regret the way I and so many of my peers fell asleep.

I’m sorry for not being brave enough in my church gatherings or family conversations or neighborhood interactions or social media exchanges, to speak explicitly when bigotry reared its head; choosing to avoid conflict rather than share the full contents of my heart, relational fractures be damned.

I’m sorry for the hubris that was always so hesitant to look inward, for fear that I might not be as evolved as I was in the story I told myself.

I make this repentance knowing full well that I have many more sins that go undiagnosed and confessed; grievous errors that I’m unable to see but that will be revealed in time. I share these words because those particular scales have fallen from my eyes, but am not too arrogant to know that there is much I still have not seen.

The only thing I am certain of, is that the dream you told us you held within your furiously beating heart is still not a reality; that the glorious mountaintop summit is still a ways above us.

And while this is true, I will need to keep learning and listening, and keep shining the brilliant light of truth into the dark corners of both who we are and of who I am.

I will need to be in two wars simultaneously: the battle outside to condemn racism as a white human being living in a nation where privilege still bends the arc of the moral universe away from justice — and the equally brutal, relentless internal battle to expose the parts of me still acting as a conscientious objector in the fight for the value of every human being.

I pray I fight in a way that honors you.

John Pavlovitz

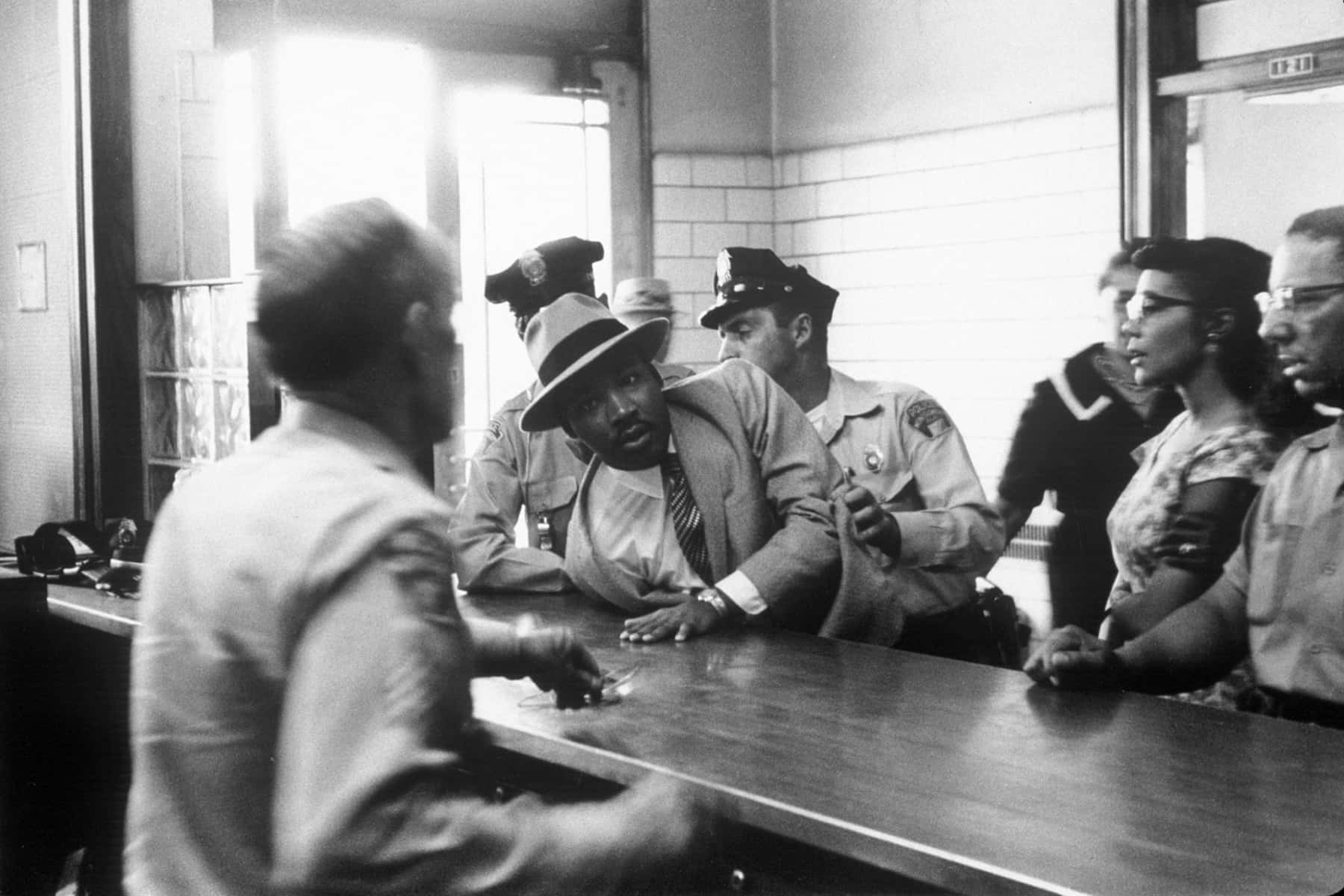

Library of Congress

The original version of this Op Ed was published on johnpavlovitz.com

John Pavlovitz launched an online ministry to help connect people who want community, encouragement, and to grow spiritually. Individuals who want to support his work can sponsor his mission on Patreon, and help the very real pastoral missionary expand its impact in the world.