Republican pundits and lawmakers are, once again, warning of an immigration crisis at our southern border.

Texas governor Greg Abbott says that if coronavirus spreads further in his state, it will not be because of his order to get rid of masks and business restrictions, but because President Biden is admitting undocumented immigrants who carry the virus. Senator Ted Cruz (R-TX) is also talking up the immigration issue, suggesting (falsely) that the American Rescue Plan would send $1400 of taxpayer money “to every illegal alien in America.”

Right-wing media is also running with stories of a wave of immigrants at the border, but what is really happening needs some untangling.

When Trump launched his run for the presidency with attacks on Mexican immigrants, and later tweeted that Democrats “don’t care about crime and want illegal immigrants, no matter how bad they may be, to pour into and infest our Country,” he was tangling up our long history of Mexican immigration with a recent, startling trend of refugees from El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras (and blaming Democrats for both). That tendency to mash all immigrants and refugees together and put them on our southern border badly misrepresents what’s really going on.

Mexican immigration is nothing new; our western agribusinesses were built on migrant labor of Mexicans, Japanese, and poor whites, among others. From the time the current border was set in 1848 until the 1930s, people moved back and forth across it without restrictions. But in 1965, Congress passed the Hart-Celler Act, putting a cap on Latin American immigration for the first time. The cap was low: just 20,000, although 50,000 workers were coming annually.

After 1965, workers continued to come as they always had, and to be employed, as always. But now their presence was illegal. In 1986, Congress tried to fix the problem by offering amnesty to 2.3 million Mexicans who were living in the U.S. and by cracking down on employers who hired undocumented workers. But rather than ending the problem of undocumented workers, the new law exacerbated it by beginning the process of guarding and militarizing the border. Until then, migrants into the United States had been offset by an equal number leaving at the end of the season. Once the border became heavily guarded, Mexican migrants refused to take the chance of leaving.

Since 1986, politicians have refused to deal with this disconnect, which grew in the 1990s when the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) flooded Mexico with U.S. corn and drove Mexican farmers to find work, largely in the American Southeast. But this “problem” is neither new nor catastrophic. While about 6 million undocumented Mexicans currently live in the United States, most of them – 78% – are long-term residents, here more than ten years.

Only 7% have lived here less than five years. (This ratio is much more stable than that for undocumented immigrants from any other country, and indeed, about twice as many undocumented immigrants come legally and overstay their visas than come illegally across the southern border.)

Since 2007, the number of undocumented Mexicans living in the United States has declined by more than a million. Lately, more Mexicans are leaving America than are coming. What is happening right now at America’s southern border is not really about Mexican migrant workers.

Beginning around 2014, people began to flee “warlike levels of violence” in El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras, coming to the U.S. for asylum. This is legal, although most come illegally, taking their chances with smugglers who collect fees to protect migrants on the Mexican side of the border and to get them into the U.S.

The Obama administration tried to deter migrants by expanding the detention of families, and made significant investments in Central America in an attempt to stabilize the region by expanding economic development and promoting security. The Trump administration emphasized deterrence. It cut off support to Central American countries, worked with authoritarians to try to stop regional gangs, drastically limited the number of refugees the U.S. would admit, and—infamously—deliberately separated children from their parents to deter would-be asylum seekers.

The number of migrants to the U.S. began to drop in 2000 and continued to drop throughout Trump’s years in office.

Now, with a new administration, the dislocation of the pandemic, and two catastrophic storms in Central America in addition to the violence, people are again surging to the border to try to get into the U.S. In the last month, the Border Patrol encountered more than 100,000 people. They are encouraged by smugglers, who falsely tell them the border is now open. Numbers released on March 10 show that the number of children and families coming to the border doubled between January and February.

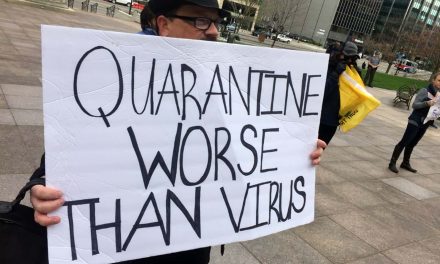

The Biden administration is warning them not to come—yet. The Trump administration gutted immigration staff and facilities, while the pandemic has further cut available beds. Most of those trying to cross the border are single adults, and the Biden administration is turning all of them back under a pandemic public health order. (It is possible that the 100,000 number is inflated as people are making repeated attempts.)

At the same time, border officials are temporarily holding families to evaluate their claims to asylum, and are also evaluating the cases of about 65,000 asylum seekers forced by the Trump administration to stay in dangerous conditions in Mexico—this backlog is swelling the new numbers. Once the migrants are tested for coronavirus and then processed, they are either deported or released until their asylum hearing.

This has apparently led to a number of families being released in communities in Arizona and Texas without adequate clothing or money. In normal times, churches and shelters would step in to help, but the pandemic has shut that aid down to a trickle. Residents are afraid the numbers of migrants will climb, and that they will bring Covid-19. Biden offered federal help to Texas Governor Abbott to test migrants for the coronavirus, but Abbott has refused to take responsibility for testing. (Migrants in Brownsville tested positive at a lower rate than Texas residents.)

There is yet another issue: the administration is having a hard time handling the numbers of unaccompanied minors arriving. Their numbers have tripled recently, overwhelming the system, especially in Texas where the state is still digging out from the deep freeze. The children are supposed to spend no more than 72 hours in processing with Border Patrol before they are transferred to facilities overseen by the Department of Health and Human Services while agents search for family members to take the children. But at least in some cases, the kids have been with Border Patrol for as much as 77 hours. Recently, there were more than 3,700 unaccompanied children in Border Patrol facilities and about 8,800 unaccompanied children in HHS custody.

The Biden administration is considering addressing this surge by looking for emergency shelters for minors crossing the border, activating the Federal Emergency Management Agency, or placing more HHS staff at the border. It has asked for $4 billion over four years to try to restore stability to the Central American countries hardest hit by violence. On March 12, the administration announced that HHS would not use immigration status against those coming forward to claim children, out of concern that the previous Trump-era policy made people unwilling to come forward.

Gо Nаkаmurа and Lаwrеncе Jаcksоn

Letters from an Аmerican is a daily email newsletter written by Heather Cox Richardson, about the history behind today’s politics