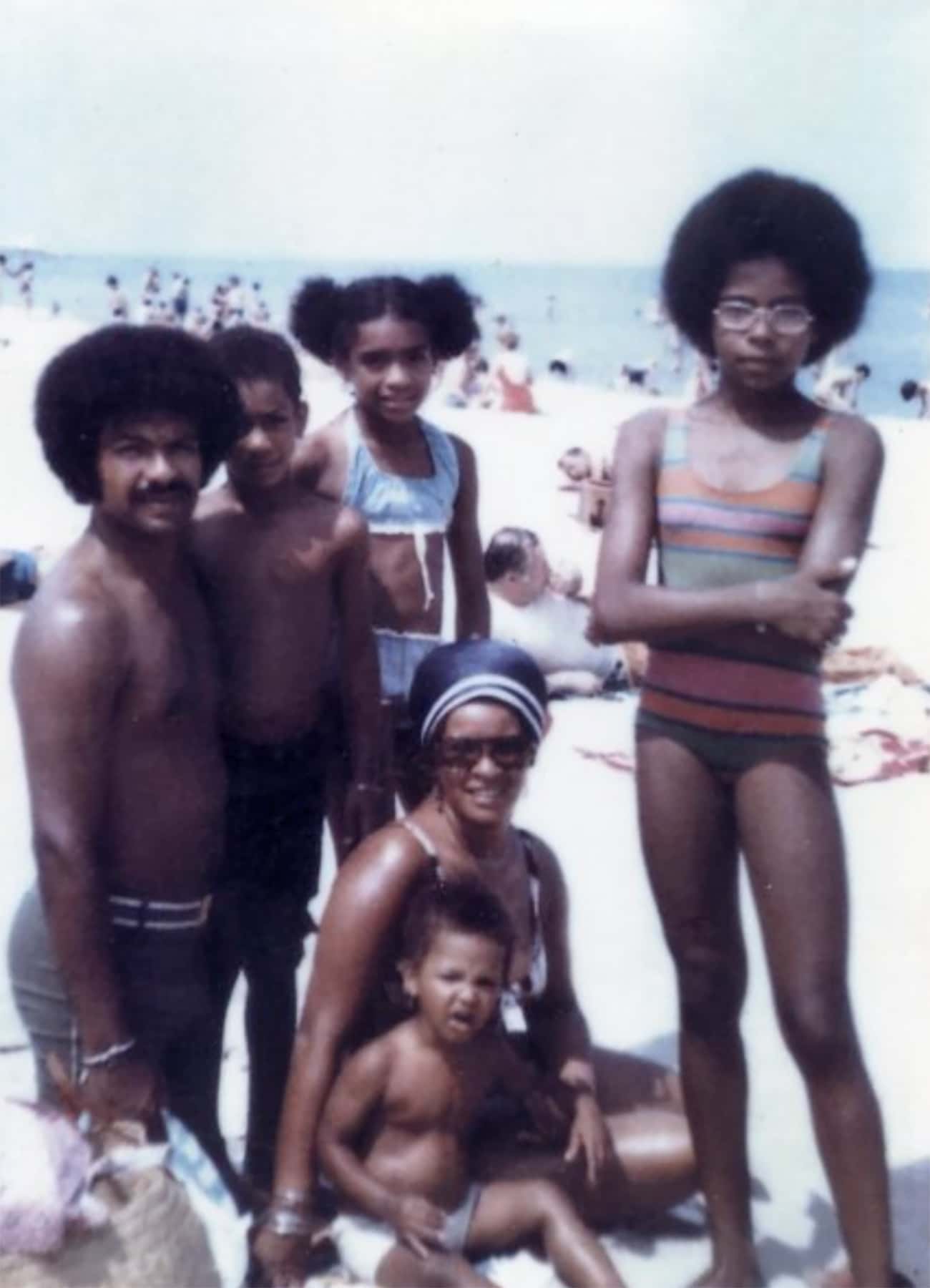

One of the first times I ever stepped foot in the ocean was at the Inkwell on Martha’s Vineyard. It was 1970 and for a kid from Ohio, the Atlantic Ocean was nothing like the creeks, ponds and swimming pools of the Midwest. The ocean left an indelible impression on me, and it is one that continues to shape my life to this day.

Thirty years later in Santa Monica, I would often find myself surfing in the Pacific Ocean at Bay St. Beach. A long stretch of sand with views of Venice Beach to the South, and the Santa Monica Pier and ferris wheel to the north. It would take years for me to learn that the spot I cherished for surf sessions at sunrise, once was known by a different name with a history that starkly contrasted the idyllic sights and sounds of the California coast. It too was called the Inkwell.

From sea to shining sea, and all points in between, there were Inkwells far too many to mention. The name Inkwell, borne of racism, was eventually embraced as a symbol of pride and resilience for the African Americans who recreated there. Inkwell, named for the color of the black men, women, and children who played on its sand and in its water.

My experiences, as vibrant and inspiring as they have become for me, are still a part of the long history of segregated spaces of recreation in America. Through threats and intimidation, legislation or enacting restrictive policies and fees, use of any or all of the aforementioned is known by many, but acknowledged by few. Even amidst the whispers, the pain of its origin story and the futility of its efforts persist.

But despite such a past, certain elements continue to linger and are increasingly dusted off and rolled out. In some communities they are modified, rebranded and watered down as beach fees, parking meters, or resident requirements. Ultimately, the purported good intentions are lost amidst the same old outcome. An outcome of restricted access and the perpetuation of a belief that certain individuals are entitled to a day at the beach, while others are not.

In recent weeks, the tried and worn proposal of beach fees and parking meters were dusted off and suggested in the Village of Shorewood as a way to address budgetary concerns. The fiscal issues facing this municipality, as with those across the country are real and present a challenge that must be addressed. Longstanding concerns, further exacerbated by the economic and emotional turmoil that lies in the wake of a global pandemic that continues to hit close to home. On the surface such a proposal may seem innocuous enough to some, but for many others it sounds familiar and rhymes with policies reminiscent of more troubled and segregated times of our nation.

Yes, these are desperate times, but now is not the time for measures that reek of desperation or a lack of consideration of how it impacts not only the fiscal bottom line, but also the moral standing of an entire community. Instead, desperate times will ideally compel a moment of pause, consideration, creativity, and efforts to build consensus on solutions that are not only sustainable but also move toward continued access and equity.

It is not believed that a through-line exists between the origins of America’s Inkwells and the proposed beach fees in a small village in Wisconsin. But elected officials represent not just a constituency of a few, but rather a community of many. They represent those who live within its boundaries and both represent and symbolize what the community should ideally stand for. In this case, one of inclusion and not exclusion, and one where new and creative solutions are considered, rather than one that is best left to history books.

I am fortunate enough to be able to trace my love for the ocean and our Great Lakes to the very first steps I took in the Inkwell. These memories have been passed down in actions that have left an indelible mark on my family, through countless hours on the beaches of Hawaii, in swimming pools in Milwaukee, and many a sunrise at Atwater Beach in Shorewood. All memories made possible by free and unfettered access. Opportunities shared, friendships made, and paths crossed with those whose lives are very different than my own, but with a love of the lake that is shared and inherently unwavering.

This vantage point, of course, belongs to just one person. One person among tens of thousands who love the beach. One person among thousands who drive by it at sunrise every day. Beach fees, parking meters, or any restriction on access to public spaces will impact countless others. The college student, the single parent, the family of five, and the person who, on a lark, just wants to head down to the lake to eat their lunch. These policies would have an inordinate impact on those historically excluded, but also extend to a community that cuts across the constructs of class, race and identity.

The emotional and spiritual draw of our Great Lake Michigan is both infinite and strong enough to overpower centuries of exclusion, and for a moment can compel us to put our differences aside. It is a place that holds the potential for a greater sense of connection, a chance to bond with nature and maybe even with one another.

Now, more than ever, is the time for such a place. Especially in our segregated city, in a very divided nation, during a time of uncertainty and doubt. But equal access to a beach where we can exhale, reenergize, or watch the sunrise with those we love, or maybe people we have never met, is important beyond measure.

And no matter how hard you try, you can’t put a price tag on that.

© Photo

Lee Matz and Kenneth Cole