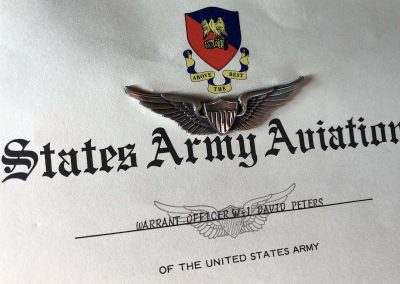

Milwaukee-native Warrant Officer W-1 David E. Peters was 22 years old when he was awarded the Bronze Star, the Distinguished Flying Cross, the Air Medal with 13 Oak Leaf Clusters, and the Purple Heart for his actions in 1966 while serving a tour in Vietnam.

Originally known as Armistice Day and renamed in 1954, Veterans Day is a federal holiday observed annually on November 11. The day was set aside to thank and honor all of those individuals who served the country in wartime or peacetime — dead or alive, although it is largely intended to thank living veterans for their sacrifices.

The Milwaukee County Historical Society (MCHS) houses over 3,000 manuscript collections, containing correspondence, both legal and personal, official documents, memorabilia, and photographs. Many collections document the history of local institutions, businesses, and events. Although the materials are interesting and even fascinating, rarely do they rise to the level of eliciting an emotional connection

However, there are certain collections that do and one in particular is Mss. 0744: the David E. Peters collection.

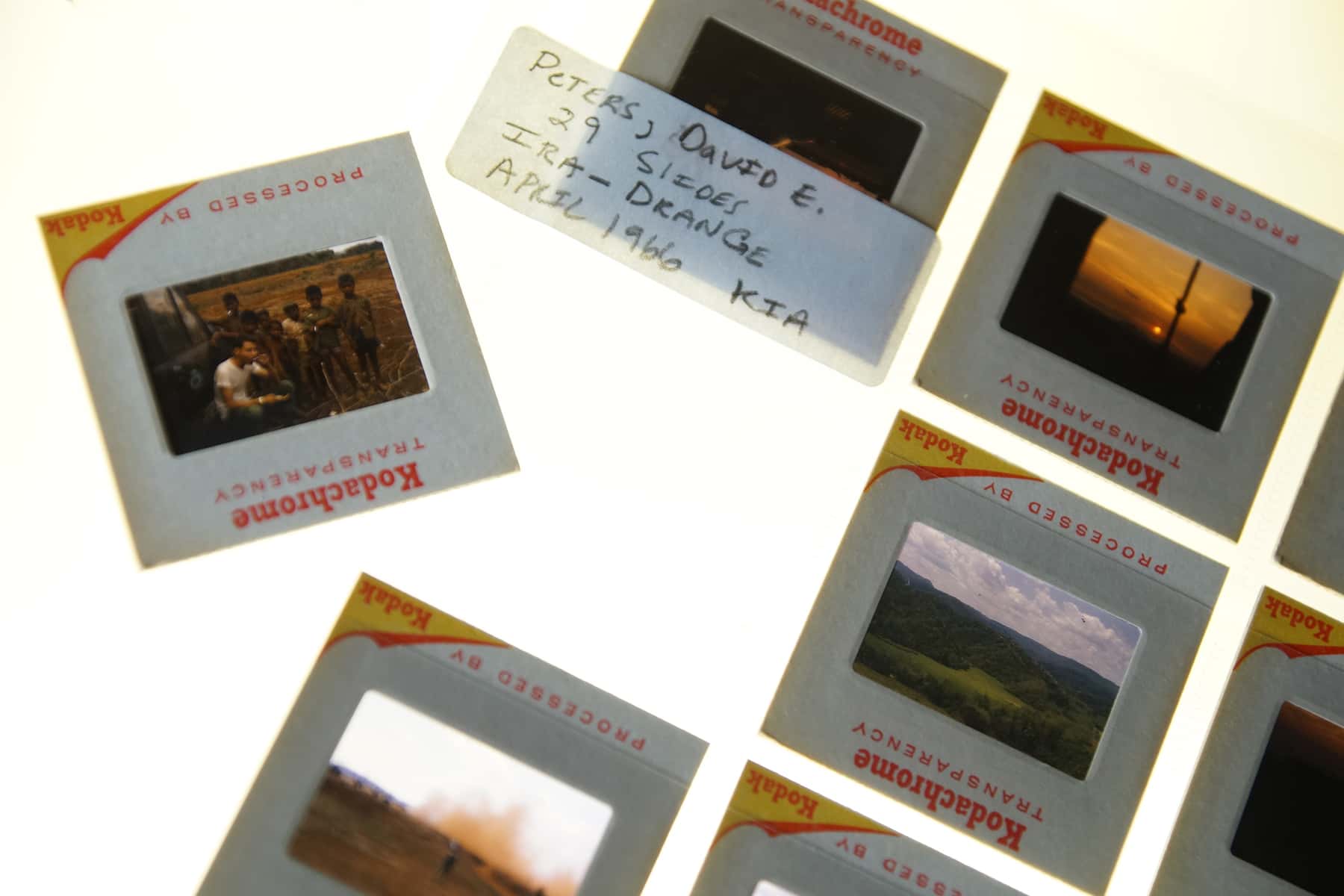

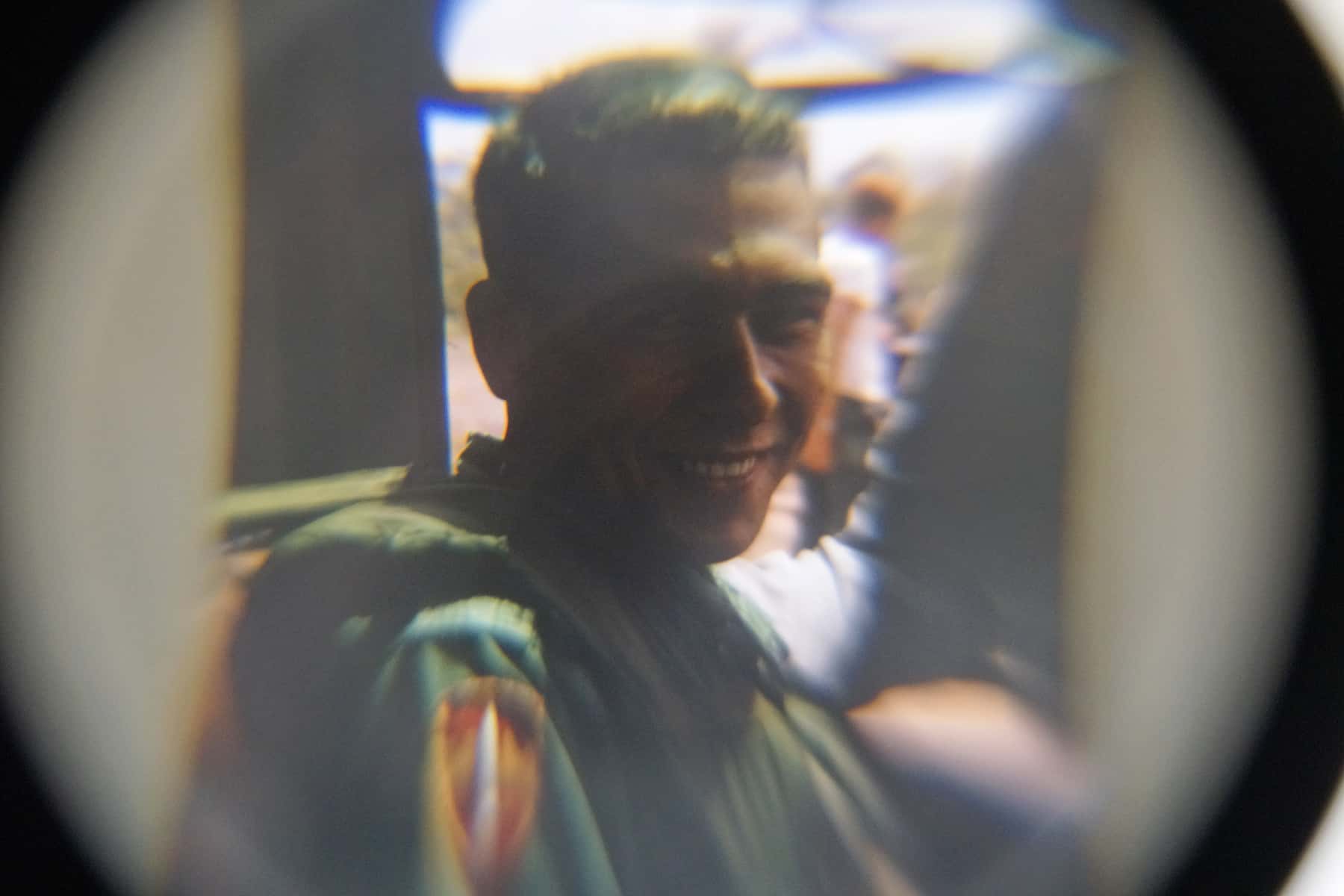

Consisting of his official military documents and fantastic personal photography, this small collection tells a monumental story about a young man from the South Side of Milwaukee.

David Edwin Peters answered the call of his country at age 20. In 1964, the young Milwaukeean enlisted in the United States Army, heeding the words of the late President John F Kennedy, “Ask not what your country can do for you – ask what you can do for your country.” Those words inspired a generation of young people who, despite the allure of the post WW II economic boom, postponed their chance at the American Dream. Instead, they committed themselves to action that challenged injustice, poverty, and totalitarianism, both at home and abroad.

Peters chose to serve in the defense of his country. After basic training, he applied to the newly organized and elite Airmobile helicopter units, then training at Fort Rucker, Alabama and Fort Benning, Georgia.

The operational doctrine of Air Mobility was intended to deliver trained airborne infantry to a desired target, provide suppressive fire, reconnaissance, and logistic support – all by helicopter. It was an entirely new theory of warfare developed by the U.S. Army. Cold War era precedents in Korea and the post-World War II colonial operations in Africa justified the refinement of airmobile tactics to meet the goals of speed, mobility, and flexibility required on the modern battlefield.

Helicopter pilot training attracted the best and the brightest, and while many washed out, David Peters more than made the grade. Upon graduating from flight school with commendation in early 1965, Warrant Officer Peters soon received his chance to serve his country, far from home in a region of the world few Americans had ever heard of – Indochina. He was part of the first airmobile division, designation 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile), that arrived in Vietnam in 1965.

Setting the stage for war

By 1951, the United States was fully supporting the French Colonial forces with weapons and financing, as they engaged nationalist Viet Minh troops in French Indochina. Although the French were defeated in 1954, and Vietnam was temporarily divided into two regions, north and south at the 17th parallel, American support continued for the pro-Western government of South Vietnam.

The United Nations sponsored Geneva Accords, the negotiated agreement that divided the former French colony into North and South Vietnam, called for elections in 1956 to unify the country. However, lacking the support of the United States, the elections were cancelled. Tensions between the Communist North and American-backed South steadily escalated and by the beginning of the new decade, had developed into armed conflict.

The Vietnam conflict was to be both a struggle for national union for the Vietnamese, and a proxy war between Cold War adversaries. The United States believed the forces of North Vietnam to be puppets of the “the international communist threat,” specifically the Soviet Union. The United States adhered to what was then known as the “domino theory,” which presumed that the fall of a non-Communist nation to Communist controlled insurgents would result in the destabilization of the entire region. As such, it would create a chain reaction like dominoes falling, as other nations succumbed to the Communist threat.

But the theory had one glaring flaw. Setting aside the philosophical arguments between the political and economic benefits of capitalism versus collectivism, the domino theory underestimated the determination of former colonized peoples to create their own political and economic future, and accepted as legitimate any form of government, including totalitarianism, as a better alternative.

A young Milwaukee hero

Many young Americans, either voluntarily or through conscription, entered an ideological fray that had turned deadly. In March 1965, the first U.S. ground forces were committed to South Vietnam. In October of that year, Warrant Officer Peters began tour as a U.S. Army helicopter pilot. By November, one month in country, Peters had already distinguished himself.

His first major engagement, and the first real test of the air mobility theory – the bloody Battle of the Ia Drang Valley in the Central Highlands of South Vietnam. Ia Drang was the first major battle between the U.S. Army and the People’s Army of Vietnam (PAVN). The battle was detailed in the 1992 book We Were Soldiers Once… and Young, written by Lt. Gen. Harold G. “Hal” Moore (Ret.) and war journalist Joseph L. Galloway.

Although assigned to the 155th Aviation Company as an assault helicopter pilot, Warrant Officer Peters was one of several pilots who volunteered for a temporary attachment to the 498th Medical Company (Air Ambulance). In that capacity he flew repeated medical evacuation flights into the thick of the Ia Drang fighting. Many of these sorties required field pick-up of wounded U.S. 1St Cavalry Division troopers and Army of the Republic of South Vietnam personnel. The flights took place mostly under the cover of darkness and in marginal weather conditions, all while taking hostile fire.

For his bravery and cool demeanor at Ia Drang, Warrant Officer Peters received the first of his thirteen Oak Leaf Clusters to his Air Medal. He was awarded his second Oak Leaf Cluster by December 1965. From January to July 1966, Peters accrued 11 more Oak Leaf awards.

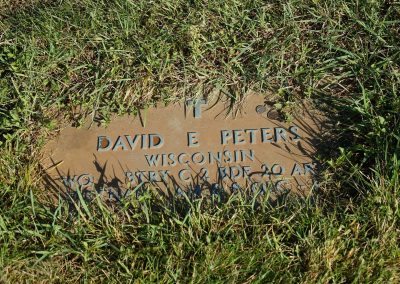

In February of 1966, Peters left the 155th and was transferred to Battery C, 2nd Battalion, 20th Artillery, 1st Air Cavalry. One of only three Aerial Rocket Artillery (ARA) units in country, his new unit provided the artillery component for 1st Air Cav units, specifically for close air support. He saw continuous action, earning more commendations, along with the praise and admiration of his comrades.

Feelings of pride and loyalty were high among U.S. Army helicopter pilots and crews during the Vietnam Conflict and, by all accounts, Warrant Officer Peters was one of the most dedicated fliers of his unit.

But like many of Milwaukee’s youth who served in the early days of the Vietnam war, and during the following decade of fighting, Warrant Officer David E Peters was killed on 20 July 1966, almost two years to the day he enlisted.

On July 20, 1966, aircraft from C Battery, 2nd Battalion, 20th Artillery, 1st Cavalry Division was shot down while conducting convoy cover along Route 14 about 25 miles south of Pleiku (South Vietnam, Quang Tri province). The helicopter came under hostile small arms (AK-47) fire, receiving at least three hits. The damage caused the pilot to broadcast on the guard channel that his aircraft was coming down in flames. There were no survivors in the crash. The crew consisted on aircraft commander WO1 David E. Peters, pilot 1LT Colin K. Nichols, crew chief PFC Clifford L. Carpenter, and gunner PFC Charles W. Smith.

Because of the helicopter, the air evacuation time of wounded personnel for medical treatment during the Vietnam Conflict was 15 minutes on the average. It is credited with saving many American and South Vietnamese lives. For Warrant Officer Peters, however, his wounds and burns were beyond medical treatment.

He was posthumously awarded both the Purple Star and Bronze Star. Warrant Officer Peters received the Purple Heart for the action on July 20, when the UH-1B (Huey) helicopter he was co-piloting was hit by small arms ground fire, crashed, and burned. The Bronze Star had been, “in the works” since January 28, 1966 and was awarded for gallantry “with complete disregard for his own safety” while repeatedly escorting medical evacuation helicopters into a small clearing, and then providing suppressing fire as the medivac helicopters loaded and took flight.

In a ceremony at Marquette University, Edwin and Angeline Peters received their son’s awards, which now now make up good share of his collection at the Milwaukee County Historical Society.

Today, the memory of David Peters will live on in his collection, as testament to the ultimate sacrifice that all military personnel face in serving their country. The historic archive also helps preserve his story for future generations of Milwaukee residents. All Americans owe a debt of gratitude and continued support to those who serve in the nation’s military, including the responsibility to insure their judicious deployment in the future.

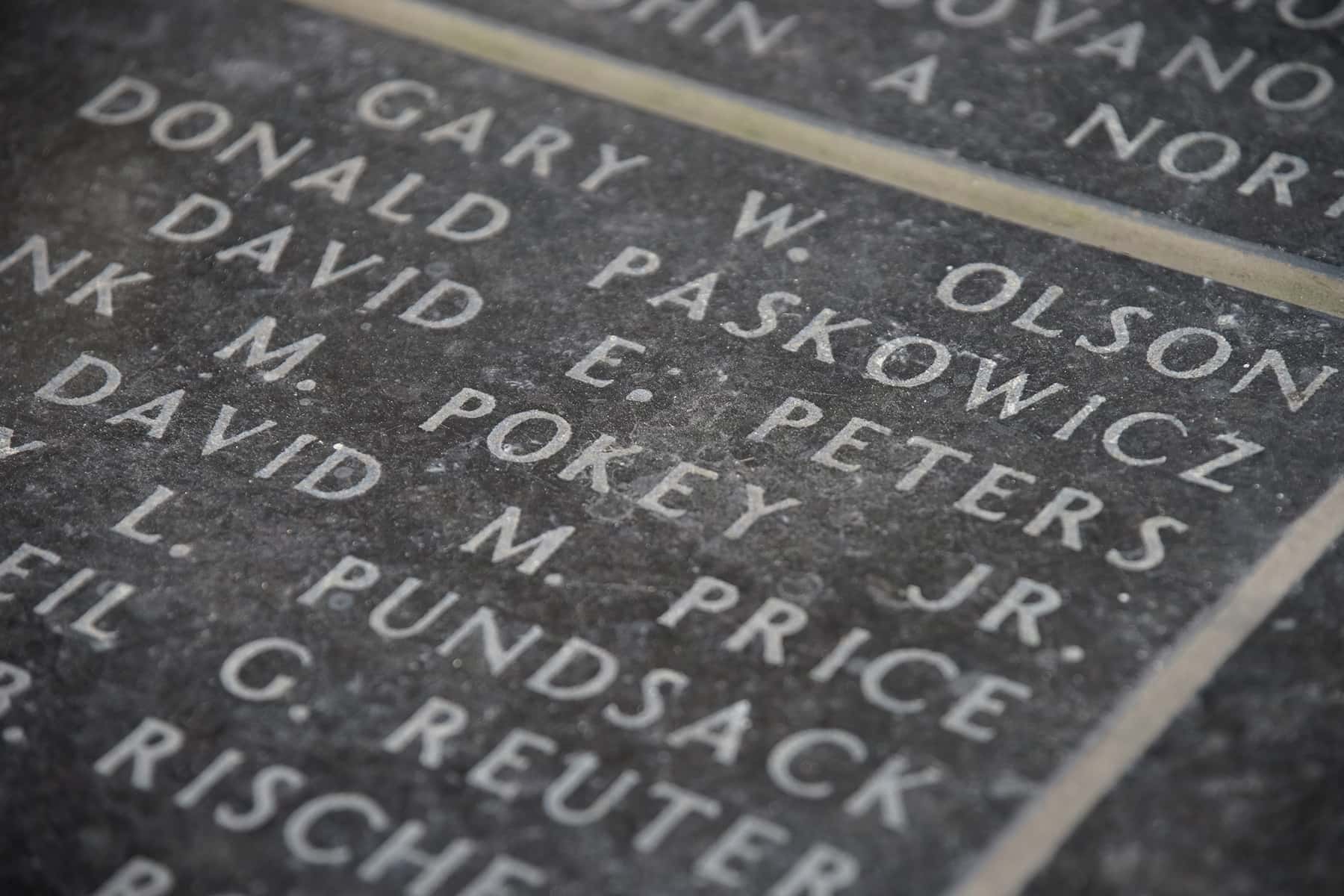

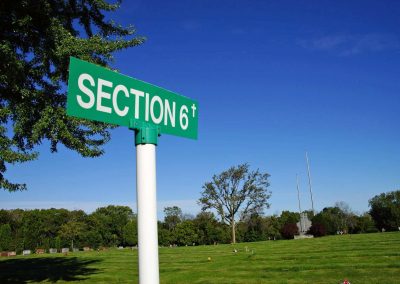

David E. Peters is honored on the Vietnam Veteran’s Memorial in Washington DC, name inscribed on Panel 09e, Line 49. His name is also listed in the Vietnam War section at the Milwaukee County War Memorial Center. His body is interred in the military section at Saint Adalberts Cemetery on Milwaukee’s south side, Section 6, Block 52, Row 14.

- Lyle Oberwise: WWII experiences in Southeast Asia influenced decades of famous Milwaukee photos

- “Oberwise in China” gains global attention with Shanghaiist article

- Long forgotten Lyle Oberwise photos show life in 1945 Kuomintang China

- Exclusive First look: Photographic treasures from Oberwise in Shanghai revealed

- Audio: A Milwaukee connection to China-Burma-India during WWII