“The islands from Charleston, south, the abandoned rice fields along the rivers for thirty miles back from the sea, and the country bordering the St. Johns River, Florida, are reserved and set apart for the settlement of the negroes now made free by the acts of war and the proclamation of the President of the United States … each family shall have a plot of not more than (40) forty acres of tillable ground.”

One of the most lasting tropes in America is the saying about immigrants “pulling themselves up by the bootstraps.” The argument is designed to show why Black people don’t have what White people have because they were too lazy to pull themselves up like White immigrants did over decades. It is not only a lie but it continues to perpetuate the myth that Black people would somehow have the same things as Whites if they would just act like White people.

One of the few times an American leader has told the truth about this topic was in June 1965. President Lyndon B. Johnson gave the commencement address at Howard University that summer. During that speech he said words that clearly demystify the myth of the bootstraps story.

“You do not wipe away the scars of centuries by saying: Now you are free to go where you want, and do as you desire, and choose the leader you please. You do not take a person who, for years, has been hobbled by chains and liberate him, bring him up to the starting line of a race and then say ‘you are free to compete with all the others,’ and still justly believe that you have been completely fair.”

In early 1865 in Savannah, Georgia, Union General William Tecumseh Sherman met with a group of Black ministers and heard words that would lead him to eventually issue his famous Special Field Order No. 15, on January 16,1865 the “forty acres and a mule” order. One of the enduring myths about that field order is that it included mules when it did not. Those twenty or so Black religious leaders had told Sherman in their meeting something very simple. They told him what Blacks needed to succeed moving forward. “The way we can best take care of ourselves is to have land, and till it by our labor…”

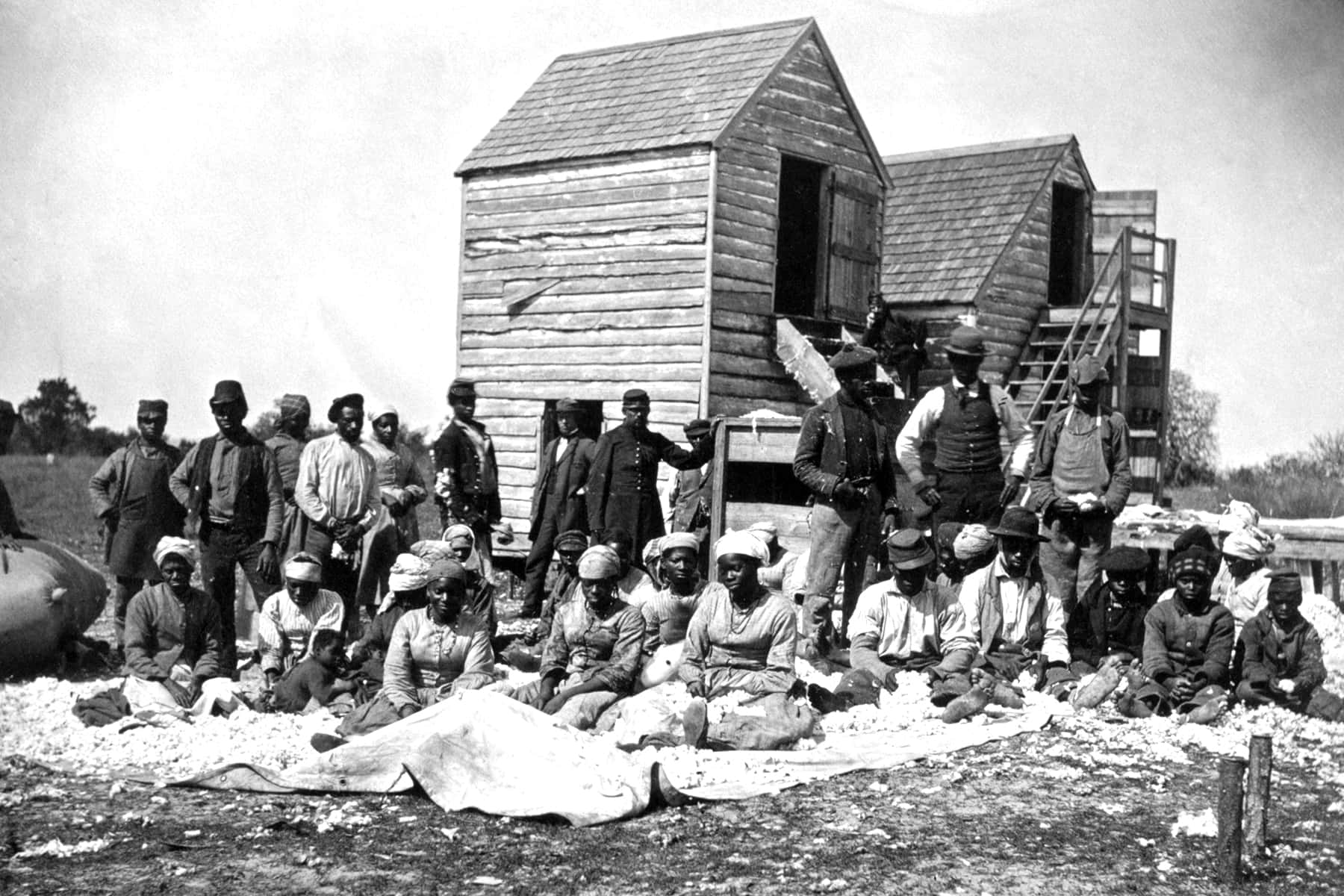

The land Sherman promised was given to formerly enslaved families to give them a chance to simply survive. They were allowed to take lots no larger than 40 acres among the 400,000 acres of land along the coast of South Carolina and Florida. The land extended from the Atlantic Ocean inland to 30 miles from Charleston, South Carolina to Jacksonville, Florida. Within six months, 40,000 “freedmen” had moved onto the land and started to till the soil.

Two months later, under new President Andrew Johnson, Lincoln’s vice president, the land was taken back and given to the former owners. These traitorous Confederates did not deserve to get the land back after causing the bloodiest war in American history. They got it anyway. The landless “freedmen”were forced off the land at gunpoint. The land was theirs for literally eight months before it was taken. A former enslaved man named Thomas Hall years later told the Federal Writers’ Project:

“Lincoln got the praise for freeing us, but did he do it? He gave us freedom without giving us any chance to live to ourself and we still had to depend on the southern White man for work, food, and clothing, and he held us out of necessity and want in a state of servitude but little better than slavery.”

This is the closest Black people have come to being given boots with straps to pull themselves up by in American history. Just 40,000 Blacks out of a total of 3,953,762 who were in captivity in 1860 received land for just eight months. That’s the truth of 40 acres and a mule.

I argue that my ancestors in Mississippi who were among that nearly 4 million African captives not only had no bootstraps, they were never in possession of the boots. How dare Americans compare White immigrants who came to this country by the millions voluntarily, to these Africans who’d been enslaved for 10 generations. These immigrants, from Germany, Poland, Italy, Sweden, Ireland, Spain, Portugal, the United Kingdom, France, and a multitude of other European countries had one thing these “freedmen” and their descendants were critically missing. White skin.

In 1829 the son of an enslaved African, David Walker, wrote and distributed in September a pamphlet he titled Walker’s Appeal. A bounty of $10,000 (roughly $243,000 in today’s money) was placed on his head immediately. He wrote these words in Article One.

“ I promised in a preceding page to demonstrate to the satisfaction of the most incredulous, that we, (coloured people of these United States of America) are the most wretched, degraded and abject set of beings that ever lived since the world began, and that the White Americans having reduced us to the wretched state of slavery, treat us in that condition more cruel (they being an enlightened and Christian people,) than any heathen nation did any people whom it had reduced to our condition. These affirmations are so well confirmed in the minds of all unprejudiced men, who have taken the trouble to read histories, that they need no elucidation from me. But to put them beyond all doubt…”

Nine months later Walker would be found dead near the doorway of his shop in Boston. How could these people described by a Black man as “the most wretched, degraded and abject set of beings that ever lived since the world began” somehow uplift themselves?

One of the least known periods of American history as it relates to Black people is what happened after the 13th Amendment when millions of Africans gained access to America as first class citizens by law for the first time, until Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on a legally segregated bus in Montgomery, Alabama ninety years later. We are literally nearly invisible in American history books over this period of time.

What set the stage for the upheaval of the twentieth century for Black people was the thirty-five years after so-called emancipation. Historian Benjamin Quarles in his amazing book, The Negro in the Making of America, describes these years as “the decades of disappointment.” Freedom brought a sense of patriotism as expressed by a convention of Black men meeting in Kentucky according to Quarles.

“We are part and parcel of the great American body politic, we love our country and her institutions and we are proud of her greatness.”

How wrong they were to have this level of faith in the nation which had enslaved their brethren for two and a half centuries. They went to work immediately after the war intending to show Whites how hard they would work to improve their lot and prove worthy of first class citizenship. Across the country a network of freedman’s aid societies were created to help them transition into their new status. The most well known agency created to assist them was the Bureau of Refugees, Freedman and Abandoned Lands—popularly known as the Freedmen’s Bureau created in March 1865 by Congress.

General O.O. Howard was the commissioner of the agency and did incredible work to provide services to the millions of newly freed Blacks. The agency provided meals, health care, and legal assistance for seven years. They established over 4,000 schools and drafted rules calling for fair wages.

Unfortunately the Bureau was flawed from the start. It could not provide the one thing most needed by Blacks—the respect of Whites. The Bureau, where it existed, reminded White southerners that they had lost the war. The were not about to cooperate with the bureau and allow Blacks to become large-scale landowners, the pathway to generational wealth building. Quarles described one of the most important elements in play during the period after the Civil War ended.

“Whatever the southerner had surrendered at Appomattox, he had not surrendered his belief that colored people were inferior to White…”

Whites began writing Black Codes, laws that would allow them to control Blacks, right after the war ended. By the end of 1865 the eleven former Confederate states were firmly entrenched in the same practices and policies, minus legal slavery, that had been in place for Blacks during their generations of enslavement. The laws were written as a replacement for the slave codes which had been used to control Blacks for decades. South Carolina in one of these codes said in any labor contract Blacks would be referred to as “servants” and that those with whom they had contracts were to be known by law as “masters.” Blacks there could not leave the plantations they worked on without express permission of these “masters.”

Many states passed laws against vagrancy, (having no visible means of support) which only applied to Black people. When arrested under this law, Black men would be sold to plantation owners and other employers who wanted free labor. This system was known as the Convict Lease System and would be in place until the early 1940s. Slavery was extended under this system for nearly three-quarters of a century after the Thirteenth Amendment supposedly ended the practice.

Under these Black Codes, Blacks in the South could not work in a profession of their choosing in many states. Louisiana and South Carolina, required Blacks to be employed only as farmers and domestics for Whites in these new laws. Blacks could not legally join militias or bear arms in many states, a clear violation of the Second Amendment. Segregated public facilities were required under law and given approval by the U.S. Supreme Court in the infamous Plessy v. Ferguson case in 1896.

In the years right after these laws started to be written, White led anti-Black riots occurred across the South. In spring 1866, White mobs in Memphis killed forty Blacks and wounded another seventy while burning dozens of Black schools and churches to the ground. In July White mobs in New Orleans killed another forty Blacks.

Instead of receiving forty acres and a mule and bootstraps to pull themselves up by, once emancipation came, Blacks were told in no uncertain terms, they would not be treated as equals. With this came decades of unequal access to the things White immigrant groups would value and use to become “true Americans.”

The federal government would give away millions of acres of land mostly to Whites using the Homestead Act. According to historian Keri Leigh Merritt, “Between 1868 and 1934, it granted 246 million acres of western land – an area close to the land mass of both California and Texas – to individual Americans, virtually for free,” in lots of 160 acres, four times the size of lots given to Blacks by Sherman.

Over 1.5 million native born and foreign born White families would rush to get this land. By the end of the program over 270 million acres had been given to mostly Whites for the cost of a simple filing fee. Literally one-tenth of the land in the country was given to Whites allowing them to begin building generational wealth and simultaneously pushing them far ahead of Blacks. Another little known law, the Southern Homestead Act passed in 1866, gave another 1.6 million White families nearly free land. Under this act only about 4,000 to 5,500 Black families received land. Merritt wrote about the long-term impact.

“The Homestead Acts were unquestionably the most extensive, radical, redistributive governmental policy in US history. The number of adult descendants of the original Homestead Act recipients living in the year 2000 was estimated to be around 46 million people, about a quarter of the US adult population. If that many White Americans can trace their legacy of wealth and property ownership to a single entitlement programme, then the perpetuation of Black poverty must also be linked to national policy. Indeed, the Homestead Acts excluded African Americans not in letter, but in practice – a template that the government would propagate for the next century and a half.”

Blacks started their freedom with literally nothing while White families were given land by the federal government for decades. Years later, under the auspices of the Federal Housing Authority (FHA), Whites would be given another important benefit denied to most Blacks. The FHA gave White borrowers access to the newly created amortized mortgage in the 1930’s setting up millions of Whites to become homeowners while making sure Blacks were mostly left out of this wealth building opportunity. From 1930-1950, ninety eight percent of all FHA loans were given to White borrowers nationwide.

When the Veterans Administration offered VA guaranteed loans under the GI Bill, there was widespread discrimination against Black GI’s. Many Black GI’s were given dishonorable discharges, making them ineligible for the GI Bill benefits. Between August and November of 1946, 21 percent of White GI’s and 39 percent of Black GI’s were dishonorably discharged from the military. The low interest VA loans were administered by local banks. Across the country banks refused home and business loans to Black Gi’s who had been honorably discharged. Whites were once again put in an advantageous position to build wealth while Blacks were shutout in city after city. In 1950 not a single non-White person in Milwaukee had a VA or FHA home mortgage loan, while over 8,000 Whites did.

A more modern study of FHA loans in Syracuse, New York found that “Of the 2,169 FHA loans issued in Syracuse between 1996 and 2000, 29 or 1.3 percent went to predominantly minority neighborhoods compared with 1,694 or 78.1 percent that went to White neighborhoods, according to the study released today by the National Training and Information Center, a Chicago-based group that provides training and research for neighborhood groups nationwide. The remainder of the FHA loans in Syracuse – 446 or 20 percent – went to integrated neighborhoods.”

Taking advantage of Blacks during the surge of house buying in the early 2000s, banks like Wells Fargo descended on Black communities issuing inferior subprime loans to people eligible for prime loans. The New York Times reported on how the bank treated Black borrowers as inferior customers. They were referred to as “mud people” receiving “ghetto loans.” The Times found that Elizabeth Jacobson, “a former loan officer at the company, recently revealed in an affidavit in a lawsuit by the City of Baltimore that salesmen were encouraged to try to persuade Black preachers to hold “wealth-building seminars” in their churches. For every loan that resulted from these seminars, whether to buy a new home or refinance one, Wells Fargo promised to donate $350 to the customer’s favorite charity, usually the church.” As the “prosperity gospel” theology spread in Black communities nationwide, preachers like Creflo Dollar (sold DVD’s saying “I want my stuff right now!”) and Joel Osteen (“God caused the bank to ignore my credit score and bless me with my first house.”) pushed Blacks to buy homes and many were trapped by big banks with inferior loans.

The N.A.A.C.P. filed a class-action lawsuit charging systematic racial discrimination by more than a dozen banks, including Wells Fargo, JPMorgan Chase and Citigroup. Tony Paschal formerly employed by Wells Fargo told the Times how it worked.

“The company put ‘bounties’ on minority borrowers…loan officers received cash incentives to aggressively market subprime loans in minority communities.”

In other very disturbing practices Paschal and Beth Jacobsen reported “the bank had given bonuses to loan officers who referred borrowers who should have qualified for a prime loan to the subprime division…Some officers told the underwriting department that their clients, even those with good credit scores, had not wanted to provide income documentation.”

“By doing this, the loan flipped from prime to subprime,” Jacobsen told the Times. She also reported “loan officers cut and pasted credit reports from one applicant onto the application of another customer…” Just three years after these reports by The New York Times, Wells Fargo settled a discrimination claim with the federal government for $175 million in 2012. The court “alleges that, between 2004 and 2009, Wells Fargo discriminated by charging approximately 30,000 African-American and Hispanic wholesale borrowers higher fees and rates than non-Hispanic White borrowers because of their race or national origin rather than the borrowers’ credit worthiness or other objective criteria related to borrower risk.” Of course Wells Fargo denied the claims made by the federal government.

So the next time someone has the inclination to use the “pull themselves up by the bootstraps” argument, remember that Blacks have never been given boots like the White people they are compared them to.

© Photo

Library of Congress