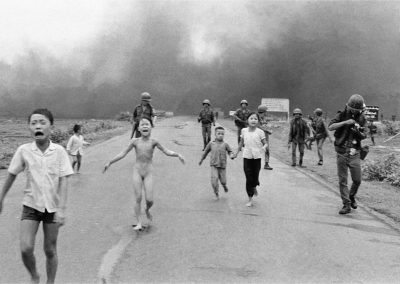

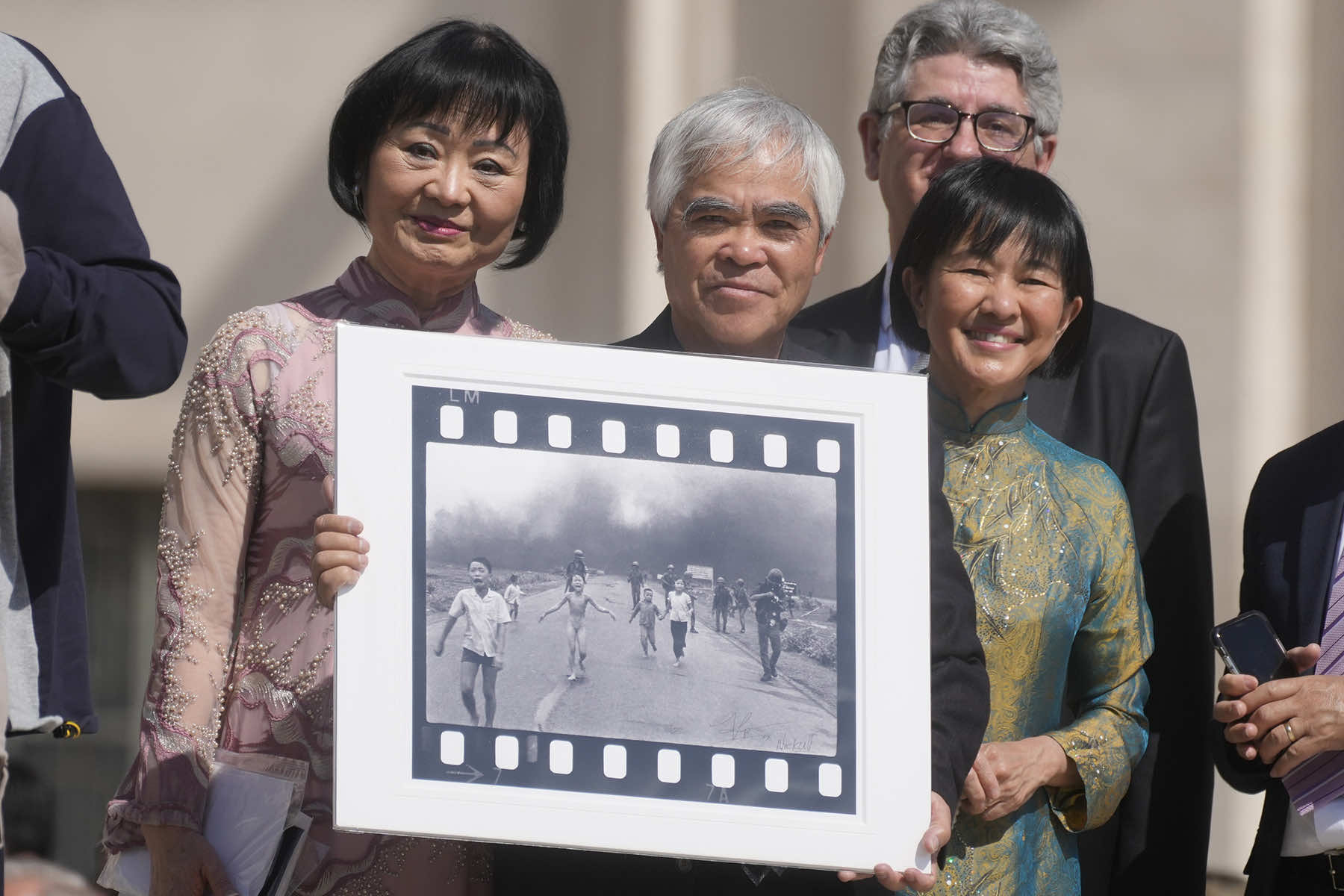

For more than half a century, Nick Ut’s searing image of a young girl fleeing a napalm attack has stood as one of the most iconic testaments to war’s human toll.

Taken on June 8, 1972, the photo captured 9-year-old Kim Phuc, naked and screaming, after a South Vietnamese airstrike engulfed her village in fire. The photograph shocked the world, shifted public sentiment on the Vietnam War, and won Ut the Pulitzer Prize in 1973. It was a moment where photojournalism did what it was supposed to do: bear witness and force accountability.

Now, five decades later, that legacy has been dragged into controversy. Not through new evidence, but through the speculative lens of a dramatized film and the institutional posturing of one of photography’s most respected organizations.

In May, World Press Photo (WPP) announced it had “suspended attribution” of the image to Ut, citing “doubt” about whether he was the true photographer. Yet in the same breath, the organization admitted it could not definitively assign authorship to anyone else.

WHEN DOUBT WITHOUT EVIDENCE BECOMES A WEAPON

The catalyst? A film called “The Stringer,” produced by Gary Knight, a man with a long history of ties to WPP, including four stints as a judge and a role as consultant to its foundation. The film centers on claims that Vietnamese photojournalist Nguyễn Thành Nghệ may have been the true photographer behind the image.

While “The Stringer” presents itself as a documentary, its blurred portrayal of history has reignited a firestorm. The issue goes beyond just one picture. It’s about what happens when legacy institutions choose politics over principle, and when prestige becomes more important than proof.

WPP’s investigation, prompted by the film’s release, yielded no conclusive evidence that anyone other than Ut took the photograph. At most, it speculated that two Vietnamese photographers, Nghe and Huynh Cong Phuc, may have been “better positioned” to capture the shot.

That language is telling. It does not assert authorship. It implies possibility. And from that, WPP drew the sweeping conclusion that the photograph’s attribution must be suspended. That decision, made despite the absence of new factual findings, undercuts not only Ut but the entire framework by which photojournalism maintains its standards.

The Associated Press, after conducting two separate investigations, stood by its long-held credit.

“Our standards require proof and certainty to remove a credit,” the AP stated. “We have found that it is impossible to prove exactly what happened that day on the road or in the bureau over 50 years ago.”

In other words, there is no new evidence to justify altering the historical record. The Pulitzer Prize Board, which awarded Ut for the photo in 1973, has also confirmed no plans to revisit its decision.

WHEN INSIDERS SHAPE THE NARRATIVE

What makes WPP’s action particularly disturbing is not just the lack of evidence, it’s the timing and the connections. Knight, the producer of “The Stringer,” is no outsider to WPP. His multiple roles in the organization raise fundamental questions about impartiality.

WPP says he no longer has any official affiliation, but the optics are unavoidable. A former insider releases a film that casts doubt on a photojournalist’s authorship, and the institution he helped shape uses that film to retroactively rewrite history.

Ut himself was never offered a proper forum to respond. His lawyer confirmed that WPP made no contact after initial inquiries before “The Stringer” was released. Instead, the organization appears to have operated in an echo chamber of implication, allowing speculation to override standard evidentiary practice. This is not how journalism or its institutions are supposed to work.

WPP has long presented itself as the global standard-bearer for visual storytelling. Its awards are considered among the highest honors in photojournalism. But this decision undermines that very credibility. When an organization begins suspending credit based on doubt alone — absent proof, and without providing a factual alternative — it is no longer serving the truth. It is serving itself.

More troubling is the precedent it sets. If speculation alone is sufficient to discredit a photojournalist’s work decades after the fact, what protection remains for others? What happens when historical evidence is replaced by creative reinterpretation? And what does it mean when the institutions meant to uphold facts instead empower their erosion?

The decision by WPP doesn’t just tarnish Ut, it exploits the ambiguity of time to retroactively challenge truth without responsibility. If this were a genuine effort to clarify authorship, it would have been accompanied by a process. There would have been an open dialogue with Ut, a transparent evidence review, and a formal rebuttal period.

Instead, WPP acted unilaterally, stripping credit without resolution. That’s not fact-finding. It’s reputational damage disguised as neutrality and enabled by institutional indecision.

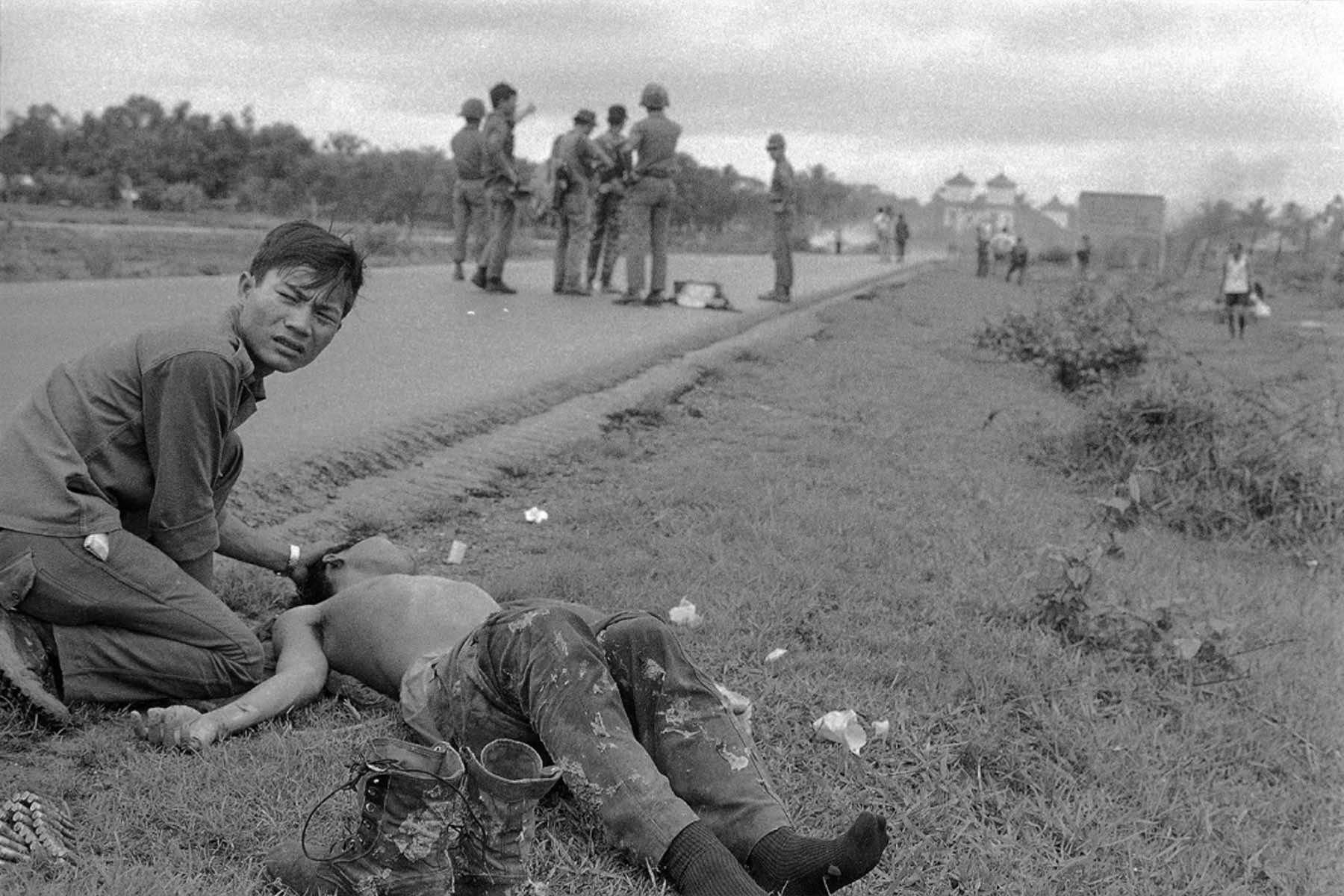

At least six non-AP journalists were on the road at Trang Bang that day, many of whom later verified Ut’s presence at every stage of the attack and aftermath. Yet none raised questions about the photo’s authorship until now.

WPP claims it could not reassign authorship, and so it suspended attribution entirely. But that logic does more harm than good. If no new author can be confirmed, and the existing attribution remains the only historically supported version, suspending it is not neutral. It is accusatory. It insinuates wrongdoing where none has been proven, and forces the burden of proof on the accused without a hearing.

In practical terms, this changes nothing and damages everything. The photo will still bear Ut’s name in archives, museums, textbooks, and Pulitzer records. But the shadow WPP has cast lingers, especially in a digital age where doubt spreads faster than truth. The legacy of a photo that helped change the world is now tangled in a controversy fabricated by a movie and legitimized by an institution that should have known better.

This wasn’t an innocent reevaluation. It was a selective rewriting of history powered by cultural capital, not evidence. Knight’s role as both a filmmaker and former insider gave him reach and narrative leverage. WPP’s leadership gave him institutional cover. Together, they’ve created a model that weaponizes suggestion without ever stating a direct claim. It’s an elegant form of reputational harm. It lets others connect the dots while you wash your hands.

Meanwhile, the two Vietnamese photographers now floated as “possible” creators of the photo, Nguyễn Thành Nghệ and Huỳnh Công Phúc, have not stepped forward with a claim. Even “The Stringer” doesn’t definitively assert authorship. It merely proposes doubt. Yet that has proven enough for WPP to take irreversible action.

The result is a precedent that will outlive this controversy. It introduces a dangerous new currency: historical suspicion. If a powerful organization can unwrite a photographer’s credit because of dramatic reinterpretation, no body of work is safe. The very concept of photographic authorship, already complex in war zones and chaotic events, becomes more vulnerable to challenge by speculation than by substance.

THE EMOTIONAL TRUTHS OF “THE STRINGER”

While the decision by WPP must be judged on its institutional behavior, it is important to distinguish that from the motivations behind “The Stringer” itself. Director Bao Nguyen has not positioned his film as an attack on Nick Ut.

Instead, he presents it as a long-overdue act of remembrance. It is a cultural and personal reckoning rooted in the experience of Vietnamese erasure from their own history.

In statements following the film’s release, Nguyen frames the story as one not just about a single image, but about power, “who gets to be seen, who is believed, and who gets to write history.”

He argues that Nguyễn Thành Nghệ, a Vietnamese military photographer and long-overlooked AP stringer, lacked the institutional protection that would have ensured his place in the record. The image, he contends, became history, but Nghệ became invisible.

This is more than a creative choice. It’s a generational trauma refracted through art. Nguyen, a Vietnamese American filmmaker whose parents lived near the 17th parallel during the war, speaks openly about inheriting the silence that surrounded their pain.

“The Stringer,” in that context, becomes a vessel. Not only to tell Nghệ’s story, but to symbolically restore the voice of a community that has long seen its suffering narrated by outsiders.

That sincerity should not be dismissed. There is emotional truth in what Nguyen presents. The grief of recognition denied, the anguish of living uncredited in a world shaped by your work, and the frustration of watching history repeat its exclusions. These are real injuries. They explain why a filmmaker might feel compelled to revisit a moment from 50 years ago and challenge the legacy around it.

But sincerity is not a substitute for verification. “The Stringer” may be a film of empathy, but it is also built on implication, on recollection, inference, and narrative framing. It offers testimony, not timestamped film negatives. It conveys conviction, not documentary proof. And while that does not make it dishonest, it does mean its conclusions must be understood as advocacy, not adjudication.

Nguyen’s moral campaign may be honest. His beliefs may be deeply held. And he may be right to criticize how Western institutions have historically excluded the Vietnamese from owning their own stories. But when that emotional crusade becomes a lever that institutions like WPP use to enact public consequences, such as suspending a photo credit without direct evidence, it leaves the realm of restorative justice and enters one of reputational harm.

There is no evidence that Nguyen acted with malice. In fact, his effort to center Nghệ’s family, including the voice of his daughter and his brother-in-law, appears thoughtful and personal. Yet the selection of this iconic war image as the battleground for symbolic justice ensures that the campaign would always be seen as a challenge to Nick Ut, no matter how carefully it was framed.

It is entirely possible for “The Stringer” to be emotionally powerful, ethically motivated, and still incomplete as a historical document. That contradiction is not a failing of the film, but it is a danger when others elevate its moral argument into a basis for rewriting fact.

What should concern every journalist, editor, and curator is not just that WPP did this, but that they did it without accountability. There is no oversight body to audit their actions. There is no due process for the accused. There is no appeal system for those caught in their public judgment. In choosing symbolism over clarity, WPP has weakened its own legitimacy making evidence negotiable.

WHAT THE AP RECORD ACTUALLY SHOWS

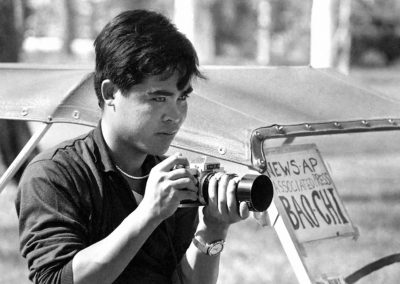

According to a comprehensive internal investigation by the Associated Press published on January 15, 2025, the record sharply contrasts with the narrative presented in “The Stringer.” In a methodical, months-long inquiry, AP retraced the events of June 8, 1972, interviewing surviving witnesses, analyzing archived film rolls, and reviewing bureau protocols in place at the time. The result was a reaffirmation.

While some specifics have naturally blurred over decades, there is no credible evidence to displace Nick Ut’s authorship of the photo.

One of the most striking revelations from the AP’s report is how the filmmakers handled contrary testimony. Several journalists who were physically present at the scene or in the Saigon bureau — including David Burnett and Fox Butterfield — told AP they had offered their recollections to the documentary team, only to be told they were “wrong.”

In Butterfield’s case, the filmmakers ended contact after dismissing his firsthand account. In multiple instances, witnesses said they were asked to sign non-disclosure agreements before seeing any of the film’s evidence, an extraordinary demand that runs counter to standard journalistic practice and raises serious questions about the filmmakers’ transparency.

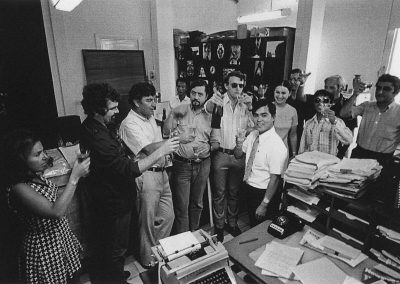

The AP’s internal records show that Nick Ut returned to the bureau that day with eight rolls of film. He stood by as they were processed by darkroom editor Yuichi “Jackson” Ishizaki. The photo’s transmission was overseen and approved by Horst Faas, not Carl Robinson — whose later revisionist claims are now being used as the backbone of the counter-narrative.

The same Carl Robinson who made no objection at the time, toasted Ut’s Pulitzer Prize in a now-public photo, and only raised doubts after Faas’s death. AP staff and contemporaries describe Robinson as embittered and inconsistent, with one of them recalling his resentment toward Ut’s later success in Hollywood as a factor.

Then there is the matter of institutional motive. The idea that the AP, or Faas, would steal credit from a Vietnamese stringer flies in the face of established practice. Faas was known for going out of his way to recognize, pay, and encourage stringers, often purchasing more photos than needed to build goodwill and ensure the AP’s competitive edge.

Multiple former staffers confirmed that misattribution of film would not only have been dishonorable, but logistically difficult, given the bureau’s detailed logging and labeling systems. Even Carl Robinson himself described Faas’s crediting process as “precisely detailed” in a 2024 post.

Ut’s photograph endures not because of who took it, but because of what it shows, an image that forced the public to reckon with the consequences of war. But credit matters. Attribution matters. And truth, especially in an age overrun by misinformation, cannot be sustained on implication alone.

WPP may argue that its decision was based on uncertainty. But uncertainty, when weaponized, becomes its own kind of lie. And if that lie is allowed to stand unchallenged, we are not preserving history, we are abandoning it.

© Photo

Gregorio Borgia (AP), Nick Ut (AP), Henri Huet (AP), Horst Faas (AP), and AP File