China’s manufacturing powerhouse of Guangdong has been battling a surge of chikungunya virus cases, and while the disease does not spread between humans, the outbreak is sending ripples far beyond Asia.

For Milwaukee and Wisconsin, where public health systems are strained by measles cases, low immunization rates, and ongoing supply chain shocks, this mosquito-borne virus is a reminder of how quickly a foreign outbreak can test local readiness.

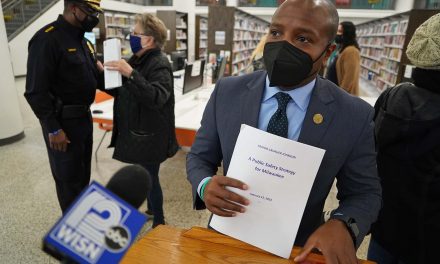

Chinese authorities have reported more than 7,000 chikungunya cases, concentrated around Foshan near Hong Kong, with workers in hazmat gear spraying disinfectant on streets, construction sites, and residential areas.

The government has gone as far as deploying drones to hunt mosquito breeding grounds, threatening fines of up to 10,000 yuan ($1,400) for residents who fail to eliminate standing water. While cases appear to be slowly declining, heavy rains and soaring summer temperatures have worsened conditions in southern China.

Chikungunya is not new, and it is not a pandemic threat like COVID-19. But the virus can still disrupt trade and public health systems. Spread by the Aedes species of mosquito — the same vector responsible for dengue and Zika — chikungunya causes fever, rash, and severe joint pain that can last for weeks. Older adults, children, and those with compromised immune systems face the highest risks.

The United States has issued travel advisories for China’s Guangdong province, warning against unnecessary trips to industrial hubs like Foshan and Dongguan. That warning matters for Milwaukee’s business community.

Wisconsin-based manufacturers, from small tool makers to auto parts suppliers, rely on imported components from the Pearl River Delta. Even a partial slowdown of Guangdong’s factories could ripple through local supply chains, raising costs and stalling production — an economic stress that could worsen under Trump’s tariffs, which remain in place on Chinese goods.

Milwaukee’s public health infrastructure is already carrying a heavy load. Measles outbreaks this year have forced local health departments to divert resources into vaccination drives, contact tracing, and school alerts.

While chikungunya is not prevented by a vaccine, because none exists, the response to any mosquito-borne illness requires surveillance, vector control, and community cooperation. Those are weak points in Wisconsin, where mosquito control programs are limited compared to southern states like Florida or Texas, which have dealt with dengue clusters.

THE MOSQUITO THREAT AT HOME

Wisconsin’s summer climate has historically been a barrier to tropical viruses. Cold winters and shorter mosquito seasons kept diseases like chikungunya from gaining a foothold. But that is no longer guaranteed.

The Aedes albopictus mosquito, also known as the Asian tiger mosquito, has been detected in southern Wisconsin counties over the past decade, including near Milwaukee. Warmer summers, increased rainfall, and urban heat islands have created new breeding habitats — from clogged gutters to backyard planters.

Public health experts have warned that even one imported case can trigger local transmission if the mosquito population is active. During the 2014 Caribbean outbreak, a handful of U.S. travelers brought the virus back to Florida and Texas, resulting in limited domestic spread.

While no large outbreak has ever taken hold in Wisconsin, the presence of Aedes albopictus makes the risk more than theoretical. Milwaukee has seen how quickly mosquito-borne concerns can surface.

West Nile virus, which is transmitted by a different species, has appeared almost every summer since the early 2000s. Local health departments monitor mosquito pools for signs of West Nile, but testing for chikungunya is not routine. That means early cases could be misdiagnosed as influenza or another viral fever, delaying detection until multiple infections occur.

A FRAGILE PUBLIC TRUST

If chikungunya were to appear in Wisconsin, public messaging could face an uphill battle. COVID-19 and ongoing debates about measles vaccines have fractured public trust in health directives. Advisories to empty standing water, allow property inspections, or support mosquito spraying might be met with skepticism or outright resistance.

Milwaukee’s neighborhoods, especially those with aging infrastructure and abandoned lots, are vulnerable to standing water accumulation — prime breeding grounds for Aedes mosquitoes. City crews have dealt with this problem for years, but a full-scale response to a viral outbreak would require community compliance. That is far from guaranteed in the current political climate, where even basic public health measures have become flashpoints.

The chikungunya outbreak also comes at a time when Milwaukee health officials are stretched thin. The city has been tackling rising cases of measles, fueled by under-vaccination among children. Every diversion of staff or budget weakens the response to other threats, and vector-borne disease is notoriously labor-intensive. Mosquito trapping, larvicide treatments, and public education campaigns all cost time and money, resources that are already scarce.

CHINA’S HEAVY-HANDED PLAYBOOK

While the U.S. debates public health spending, China is taking no chances. In Foshan, patients with chikungunya have been forced into hospitals for a minimum of one week, even if symptoms are mild. Authorities briefly implemented a two-week home quarantine, though it was dropped because chikungunya does not spread person-to-person.

Workers have been filmed spraying disinfectant around office buildings, apartment complexes, and parks before residents can enter. The tactics echo the extreme measures China used during COVID-19 lockdowns, when entire neighborhoods were sealed off and residents were monitored by drones and facial recognition systems.

This time, enforcement has included threats of power shutoffs for households that fail to remove stagnant water, an approach unthinkable in Milwaukee or anywhere in the U.S., but one that underscores China’s determination to suppress the outbreak before it affects trade or invites international scrutiny.

A WARNING MILWAUKEE CAN’T AFFORD TO IGNORE

Unlike China, Milwaukee can’t deploy surveillance drones or fine residents into compliance. The city’s health strategy must rely on transparency, community outreach, and trust — three things that have become harder to maintain after years of pandemic-related disinformation and political interference.

Warnings about mosquito-borne diseases might not carry the urgency they deserve, especially when the symptoms aren’t dramatic and the name “chikungunya” is unfamiliar to most. But that unfamiliarity is dangerous. In the event of a local case, hesitation or indifference can delay response efforts.

Doctors in the Midwest aren’t routinely screening for chikungunya. Fever and joint pain are common enough to be mistaken for viral flu, Lyme disease, or even post-COVID complications. Without rapid diagnostic testing or clinical awareness, the first signs of transmission might be missed.

And even if Milwaukee avoids infections altogether, the economic fallout may still land hard. Wisconsin’s manufacturing economy is tied to Guangdong’s factories in ways most consumers never see. From electrical components to machine tools, supply chains that run through Dongguan and Foshan pass through importers and distributors in Milwaukee’s industrial corridor.

A slowdown — or worse, shutdown — of these Chinese hubs could hit small and midsize manufacturers that are already squeezed by inflation, labor shortages, and tariff pressures. Trump’s tariff regime continues to drive up costs for imported goods.

If chikungunya-related quarantines reduce output in Guangdong, Milwaukee-area businesses could face both supply shortages and price hikes, with little federal relief expected. The combination of foreign health crisis and domestic policy rigidity forms a squeeze Wisconsin is painfully familiar with, seen most recently in COVID-era PPE shortages and semiconductor delays.

Even before any economic impact is felt, public officials in Wisconsin would be wise to begin surveillance planning now. Local mosquito mapping, larvicide programs, and public education on preventing standing water should not wait for the first case to arrive. These are low-cost interventions that could prevent an expensive response later.

It’s also a critical moment to reassert public health messaging, especially in neighborhoods that have been historically underserved or targeted by misinformation. Milwaukee’s south side, where older housing stock and poor drainage are common, could become a flashpoint for mosquito activity. But efforts to inspect properties or recommend chemical spraying could meet opposition if not handled with care, community buy-in, and credible messengers.

Milwaukee’s own environmental health reports already acknowledge the challenges of monitoring and controlling urban mosquito populations. But chikungunya raises the stakes. Unlike West Nile virus — which has a relatively low symptomatic infection rate — chikungunya almost always causes noticeable illness, meaning any cluster will get public attention fast. If that happens, Milwaukee officials will need to respond with more than platitudes or reactive press conferences. The time to prepare is now.

At the state level, coordination will be key. The Wisconsin Department of Health Services does not currently list chikungunya as a priority pathogen, though it tracks other arboviruses. That may need to change. Surveillance protocols, laboratory testing capacity, and cross-agency mosquito control coordination should be elevated, especially with Aedes albopictus slowly expanding its range in the region.

The message from China is not that the U.S. should emulate its authoritarian tactics. But it is a signal that chikungunya can escalate quickly under the right environmental and political conditions. With extreme summer weather now routine in the Midwest, Wisconsin is not immune to the same triggers — flooding, heat, and neglected infrastructure.

Milwaukee has already shown how underestimating a virus can stretch public resources, divide communities, and shake trust. Chikungunya doesn’t need to become the next COVID to matter. It just needs to appear once — in the right mosquito, at the wrong time — and the costs will arrive faster than any warning from overseas.

Whether this becomes a health story, an economic story, or both, will depend on whether the China outbreak is seen as a cautionary tale or a distant problem that’s easy to ignore.

© Photo

Chinatopix (via AP)