As the new school year approaches, Wisconsin schools face significant challenges, including class sizes that have grown faster than the national average, an increasing number of students living in poverty, and a reduction in state support for education.

Schools have long been an engine of our state’s economic growth. Wisconsin has depended on a well-educated workforce, shaped by excellent public schools, to lay the foundation for our prosperity. To ensure that Wisconsin is competitive in the future, our schools must have the resources to offer students a high-quality education. Only then can we create a future workforce that is well-qualified and globally competitive.

FEWER TEACHERS IN WISCONSIN CLASSROOMS

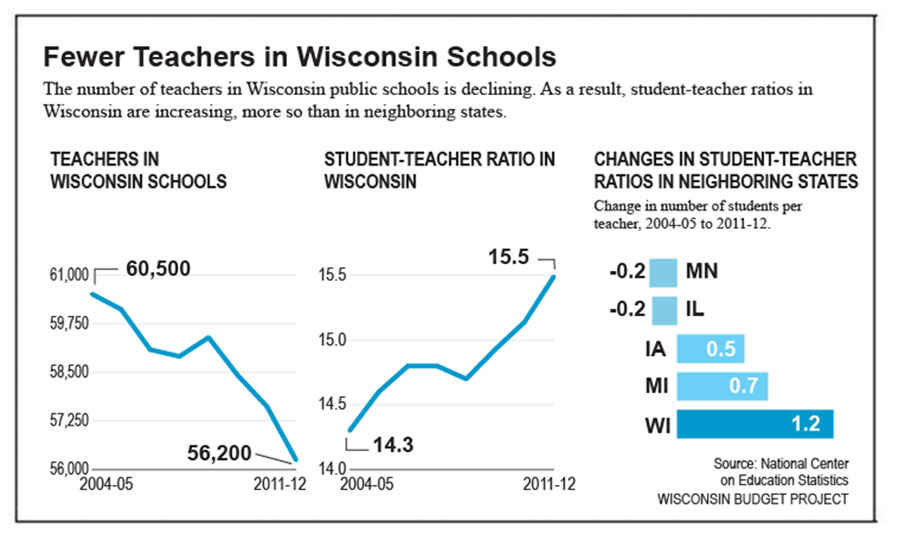

Wisconsin classrooms have fewer teachers, resulting in more crowded classrooms and less individualized attention for students. Over the last seven years, the number of teachers in Wisconsin public schools has fallen by 4,300, even as student enrollment has increased slightly.

In the 2011-12 school year, there were 56,200 teacher full-time equivalents (FTEs) in Wisconsin public schools, down from 60,500 in the 2004-05 school year — a decrease of 7.1%. The trend of fewer teachers in Wisconsin dates back to before the collective bargaining changes that state lawmakers approved in 2011.

The decline in the number of teachers in Wisconsin has resulted in higher student-to-teacher ratios in Wisconsin. Having fewer students for each teacher helps students learn better, but in Wisconsin the trend is going in the opposite direction. In 2004-05, Wisconsin had 14.3 students per teacher; that number had risen to 15.5 students by 2011-12.

Wisconsin has 1.2 more students per teacher in 2011-12 than in 2004-05; nationally, schools averaged an increase of 0.2 students per teacher over this period. Only three states — California, Arizona, and Nevada — had larger increases in student-teacher ratios than Wisconsin between 2004-05 and 2011-12.

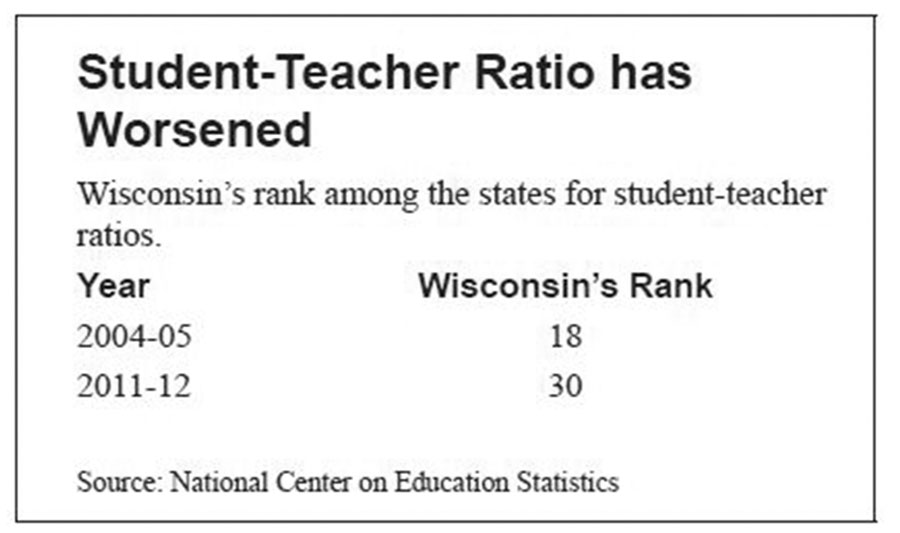

Wisconsin still has fewer students per teacher than the national average, but our rank has been dropping. In 2004-05, Wisconsin ranked 18th among the states in the number of students per teacher. By 2011-12, Wisconsin’s ranking had dropped to 30th.

Wisconsin had by far the largest increase in student-teacher ratios compared to neighboring states. Student-teacher ratios in two states that border Wisconsin — Minnesota and Illinois — actually dropped over this period. The number of students per teacher increased in Iowa and Michigan, but not nearly to the extent that it did in Wisconsin.

This analysis relies on national figures to enable comparisons between Wisconsin and other states. More up-to-date state-level figures show that the number of teachers in Wisconsin has increased slightly since the 2011-12 school year, but not enough to make a meaningful reduction in classroom sizes.

A RISING TIDE OF POVERTY IN WISCONSIN SCHOOLS

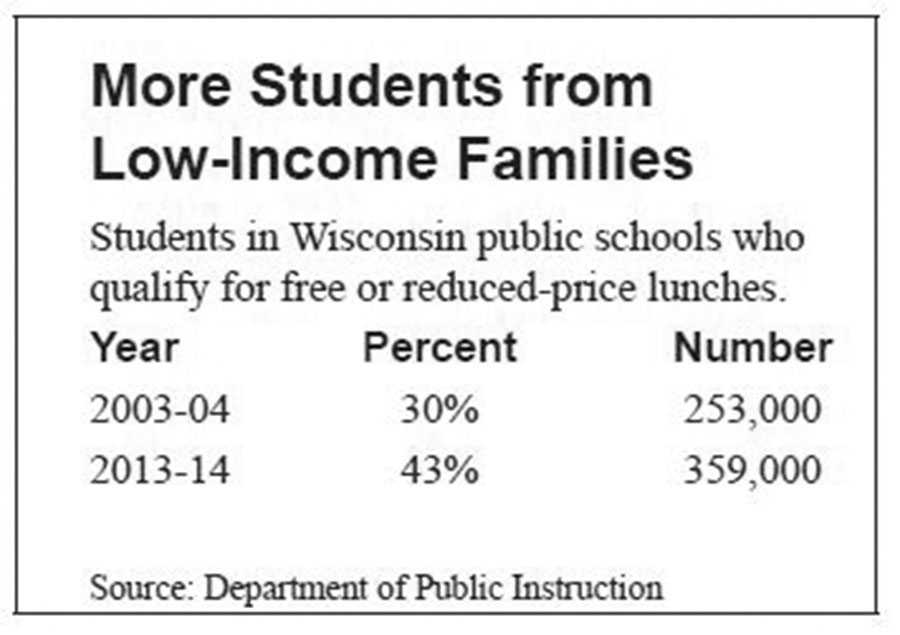

The number of Wisconsin children who are from low-income families has climbed for ten straight years, according to the Department of Public Instruction.

The rising number of low-income students presents challenges for Wisconsin schools. Children from low-income families lag their peers in educational achievement. They also are less likely to graduate from high school and become well-educated, healthy members of Wisconsin’s skilled workforce.

In the 2013-14 school year, 43% of Wisconsin children in public schools — or 359,000 children — were eligible for free or reduced-price school lunches, A decade earlier, only 30% of students qualified for free or reduced lunches.

The share of children coming from low-income families increased only slightly between the 2012-13 and 2013-14 school years, an indication that economic hardship among students may have reached a plateau. But even if that is the case, the number of students receiving free or reduced-price lunches — a common yardstick of poverty in schools — would have to drop by more than 100,000 students in order to return to a level similar to that of a decade ago.

Students in families earning less than 130% of the federal poverty level qualify for free school lunches. For the 2013-14 school year, students from a family of four earning less than about $31,000 would qualify. A much smaller number of students in families earning between 130% and 185% of the poverty level qualify for reduced-price lunches.

In each of Wisconsin’s five largest school districts — Milwaukee, Madison, Kenosha, Green Bay, and Racine — more than half the students are from low-income families and qualified for assistance for school meals. More than 8 out of 10 students in Milwaukee Public Schools were from low-income families in the 2013-14 school year. Put another way, about 69,000 children in Milwaukee Public Schools received assistance to help pay for school lunches.

More Wisconsin schoolchildren will come to school well-nourished and ready to learn, thanks to a new federal program that allows high-poverty districts to offer free meals to all students. Starting with the 2014-15 school year, a number of school districts, including Milwaukee and Beloit, are offering free breakfast and lunches to all students. Some other districts, including Madison, have started to offer free meals to all students at certain schools. By taking this step, schools can eliminate paperwork needed to track which students qualify for assistance, help students from low-income families who may be falling through the cracks, and make sure that all students have access to the meals they need to succeed in the classroom.

SHRINKING RESOURCES AND UNCERTAINTIES ABOUT FUTURE FUNDING

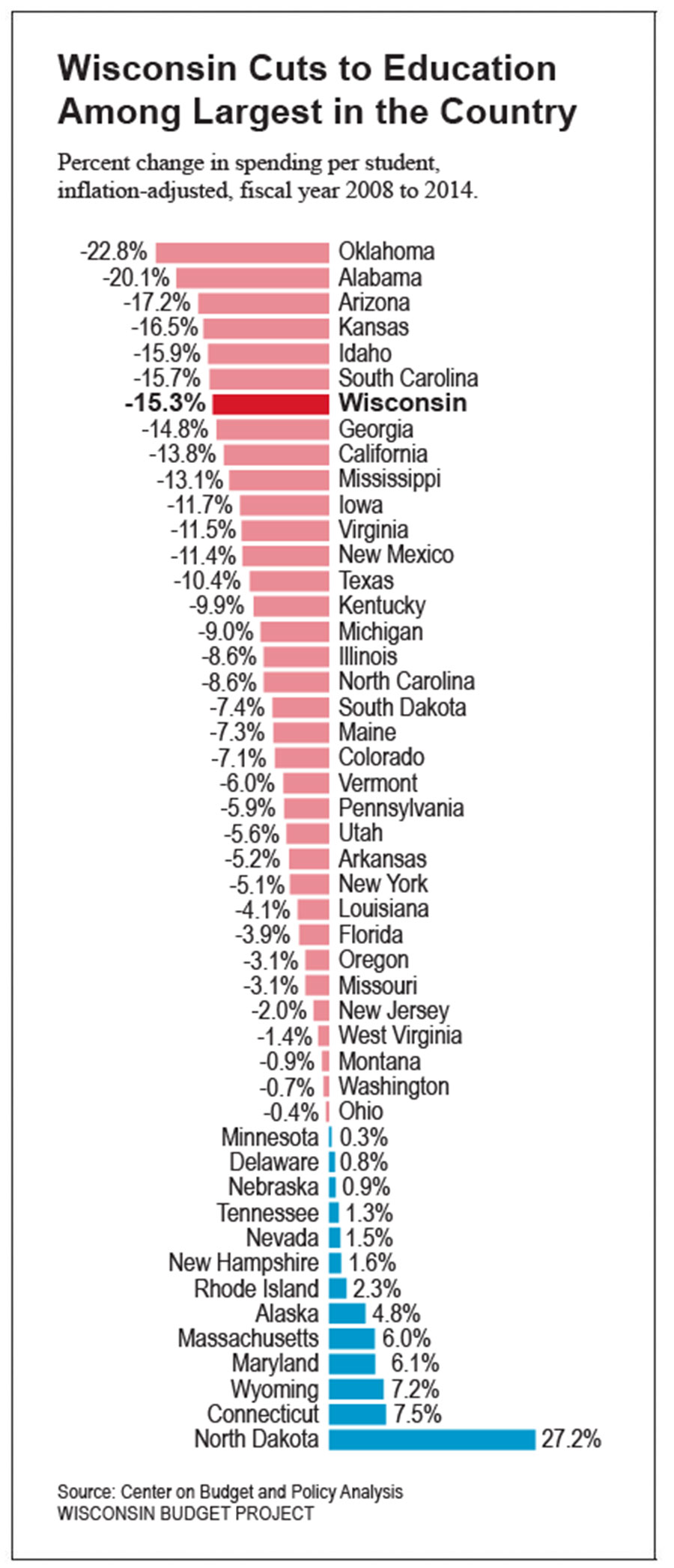

Wisconsin’s public education cuts are among the deepest in the country. The state budget provided 15% less resources for public schools per student in 2014 than in 2008, according to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, a nonpartisan research organization. Only six states, mostly in the South and West, made deeper cuts over this period, measured as a percentage change in spending per student.

When measured as dollars lost per student, Wisconsin’s cuts to public education over this period are second only to Alabama. Wisconsin provided $1,038 per student less in state support for public schools in 2014 than in 2008.

Changes to the state retirement system and collective bargaining rules made in 2011 allowed school districts to cut compensation for teachers and other school employees. Some school districts have been able to use these savings to compensate for cuts in state support, and have avoided scaling back academic programs. Other school districts have been forced to eliminate courses in core subject areas.

At the same time lawmakers were cutting state support for schools, they passed tax cuts that add up to $1.9 billion over four years. The tax cuts didn’t do much to lower tax bills for Wisconsin’s lowest-wage earners, but they did drain revenue that could be used for education or other priorities.

Cuts in state aid and uncertainties about future funding have caused turmoil in Wisconsin schools. But even before the significant budget cuts and changes to collective bargaining that began in 2011, the trends in Wisconsin were toward fewer teachers, more crowded classrooms, and higher levels of poverty.

Tamarine Cornelius

- Wealth gap leaves Milwaukee families of color financially vulnerable

- Income inequality adds to growing divide in Milwaukee

- Rising tide of poverty adds to challenges in Milwaukee Schools

- State Corrections policies and the high cost for Milwaukee

- Mortgage lending structures reinforce segregated poverty

Originally published on wisconsinbudgetproject.org

Help support the Wisconsin Budget Project with a donation. The organization is engaged in analysis and education on state budget and tax issues, particularly those relating to low-income families. It seeks to broaden the debate on budget and tax policy through public education and by encouraging civic engagement on these issues.