This article is part of a series that connects Milwaukee’s current social conditions with efforts in Alabama cities to publicly recognize their racial histories, to document the 1960’s Civil Rights Movement, and to extend and expand the Movement’s goals towards peace and reconciliation.

Temporary “medallions” painted on the sidewalk announce Montgomery as one of the New York Times 52 places to visit in 2018. Its decade long revitalization plan is visible in building restored buildings, a renewed riverfront, and history-based tourism. It is from here that the Confederate States of America installed its government to fight the Civil War; from here that religious leaders inaugurated the modern Civil Rights Movement to fight segregation; and it is from here that legal leaders have initiated a racial reconciliation movement to fight social injustice, and specifically to secure criminal justice reform.

In recent years, Montgomery has recognized and educated visitors and residents about Alabama’s brutal racial history, e.g., development of the Civil Rights Memorial Center (1989), the Rosa Parks Museum (2000), and the Freedom Rides Museum (2011). However the Equal Justice Initiative is moving to the next level of the civil right movement. Its Legacy Museum and its National Memorial for Peace and Justice are 2018 additions to the Civil Rights Trail. They are taking a fork on that Trail that includes civil rights education but which purposefully wends a path towards racial reconciliation: documenting and memorializing racial terror to ultimately pursue healing; pursuing justice system reforms to deracinate deeply-rooted racial inequities.

In 2018, Milwaukee itself completed its own commemoration of the 50th anniversary of the 1968 Civil Rights marches, saw the groundbreaking for the soon-to–be-reopened America’s Black Holocaust Museum – located on the recently dedicated Vel R. Phillips Avenue (honoring the Milwaukee civil rights champion who died in 2018), and realized the Milwaukee County Historical Society’s approval of an historical marker designating the site of the only documented lynching in Milwaukee.

THE LEGACY MUSEUM

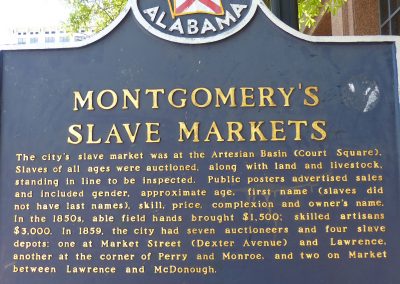

Persistently wending through Montgomery is the Alabama River, by which millions of African, Caribbean and American black slaves in antebellum Alabama were transported for auction. Pending auction they were held in brick warehouses lining the streets connecting the river to the auction block.

The Legacy Museum occupies one of the original warehouses. Visitors must pass through a prominent security checkpoint and upon entry must turn off cellphones—focus is deliberately redirected away from picture-taking, videography or Facetime chats. Due to “timed” admission tickets, visitors wait in a dark-lit corner of the converted slave warehouse for a short while before entering through a darkened tunnel-like passageway, ramped downward, into the museum. Along the ramp, motion-activated holograms of four slaves, depicted held in barred cells, successively and respectively narrate their tortured enslavement and their thoughts as they await the auction block. Visitors flow into the open museum displays, and start to literally walk an historical timeline of racial inequities and injustices in America.

The very thesis of the museum, and of its parent/sponsor the Equal Justice Initiative, are on display: portrayed is a direct line of sustained and evolved racial injustice that can be drawn – from slavery of the 18th century to mass incarceration in the 21st century (and terrorism, lynching, Jim Crow, discriminatory policing practices and race-biased sentencing along the continuum) — with the rule of law creating and sustaining every point on the racial injustice timeline.

Visitors meander, without docent or interpreter, through the various displays which repeat in different formats – videos, charts, pictures, writings, interactive modules – the museum’s themes and information. Very few artifacts actually are exhibited; objects are essentially only in two displays. The first is a central pillar displaying various original signs that prohibited interracial connections— e.g., placards designating by race bathroom and bubbler use; signs expressing racial discrimination in employment and entertainment access. The second is a series of shelving exhibiting uniform-sized and labeled glass jars containing variously-colored and textured soil samples—researched and collected from lynching sites throughout the country. It is stunning. It is a foretaste of the contextualizing of lynching memorialized at the Legacy Museum’s companion site: The National Memorial for Peace and Justice.

THE NATIONAL MEMORIAL FOR PEACE AND JUSTICE

A separate “timed” admission ticket is required for the Memorial, where even on a hot Alabama Sunday (when most places are closed after church services) busses of church groups and families crowd the site. From Montgomery proper, visitors drive a steep hill that wends its way to the six-acre Memorial set atop the hill, the grass surrounding it giving a pastoral feel. Approaching from downtown, the covered pergola on the hilltop appears to rest on a colonnade of pillars, not unexpected of formal memorials such as Lincoln’s in D.C. But upon getting closer the “pillars” give way to reveal instead hanging steel monuments, more than 800, the size of coffins. The pergola turns out to be only part of the Memorial; the grassy hill has a crushed-stone path cut into it that wends up to the top thereby becoming integrally incorporated into the Memorial’s physical and symbolic design.

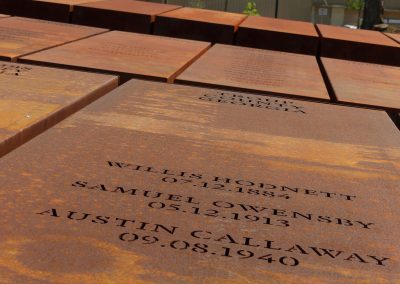

While the Legacy Museum explains the journey from slavery to mass incarceration via raw legal, historical and pictorial facts, the Memorial explains the same journey via the arts instead – literature, sculpture, and design. No docents or interpreters intervene on the journey; the visitor must encounter the Memorial on one’s own, personally. At the center of the “journey” are the hanging steel monuments, one for each American county with a least one documented lynching; etched on each of the newly rusting monuments are the names of those men, women and children who are documented as lynched in each county. More than 4000 persons are listed. Visitors walk on a boardwalk-like wooden floor that slopes intentional from corridor to corridor. At the first corridor the steel monuments are at eye level but upon walking down the slope of the second corridor, the monuments give the impression of slowly rising overhead; wooden, two-inch “boxes” emerge from the floor directly under the monuments, seemingly modeling a scaffold’s trap door. The intended physical effect of the design is palpable.

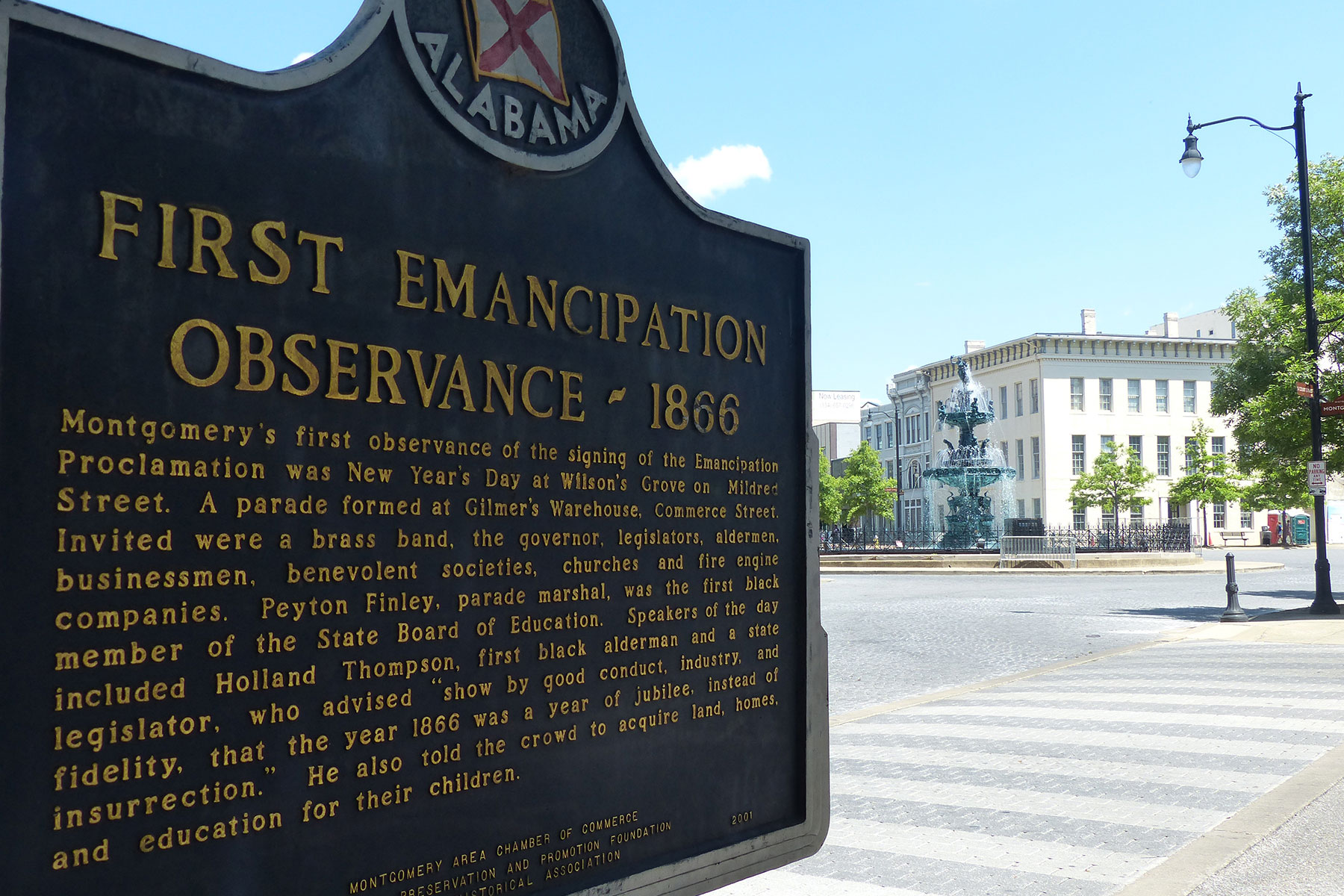

Pass the remaining corridors and fountains is the entrance to the Memorial’s center —another path upwards to the central hilltop the design of which suggests an actual lynching site. From this vantage point, through the steel monuments, Montgomery sits. There is Alabama’s state capital, where Jefferson Davis took the oath of office as the Confederacy’s president. And there fewer than 500 feet from the Confederacy’s capital is the Dexter Street Church, where one hundred years later a young Martin Luther King, Jr. vowed to boycott segregated busses and ultimately led the Civil Rights Movement. And five blocks from the church there is Court Square, overwhelmed by a massive fountain of Greek mythological figures – all overshadowing the site where antebellum Montgomery hosted and boasted of arguably the most robust slave auctions in America. On the northwest side of Court Square is the bus stop at which Rosa Parks paid her fare but refused to pay heed to segregated seating – ultimately sparking her arrest and sparking legal desegregation of transportation.

The rest of the Memorial is outdoors — with sculptures and meditation places and Monument Park. In the park lie duplicates of the hanging steel monuments – in alphabetical order by state. The intent and hope of the Memorial design is that every county will claim and display its own lynching history – to memorialize and bring reconciliation locally, in the very places where such violent racial oppression occurred. Unclaimed duplicates will be reminders to future visitors that counties remain unreconciled with their respective segregation histories.

MILWAUKEE’S ONLY DOCUMENTED LYNCHING

The National Memorial does not include any steel monuments citing Wisconsin counties with documented lynchings. However, the Milwaukee County Historical Society has initiated the process for claiming registration in the Memorial, potentially receiving a steel monument but also intending to include a glass jar of soil from the site of George Marshall Clark’s lynching in Milwaukee’s Third Ward. However, Milwaukee’s application cannot be processed until 2019; the success of the National Memorial’s program has resulted in a long cue of local county registration applications.

During summer 2018, the Milwaukee County Historical Society (MCHS) designated as a Milwaukee County landmark the site of Clark’s 1861 lynching, at what is currently the northwest corner of Buffalo and Water Streets. MCHS, the only organization authorized to designate Milwaukee County historically significant landmark sites, annually seeks public nominations and holds public hearings for input. The Society recognized the lynching site nomination as part of Milwaukee’s history that is important in itself and relevant to our city today. The editorial staff of the Milwaukee Independent nominated the site for designation as a historically significant landmark. During the review process, MCHS considered previously published Milwaukee Independent articles about the lynching.

The Society anticipates that the County marker will be erected and the site so dedicated during 2019. In the meantime, the designation appears on the Milwaukee County Landmarks website.

The lynching of Clark as an historical event was lost for decades. However its importance in mid-19th century Milwaukee was significant. Many blacks left the city over the incident, concerned for their safety. Continued historical research regarding this incident could better contextualize the event.

This is a historical summary of the event, quoted from an article previously published by the Milwaukee Independent.

“On a Friday evening, September 6, 1861, Clark, 22 years old, was walking through the Third Ward with James Shelton, also African-American. They encountered two men of Irish descent, Darby Carney and John Brady. An argument ensued and escalated into a fight, in course of which Carney suffered a stab wound to his abdomen and Brady received a severe slash on his shoulder. Clark and Shelton fled, stabbing a bystander in the process but were soon captured and placed in jail, then located at the northern end of today’s Cathedral Square. Confined in a large room at the rear of the jail, Clark and Shelton heard the mob approaching. Shelton was able to hide as the crowd burst in, but Clark was spotted, dragged from the jail, and beaten until, as one history puts it, he was “more dead than alive.” He was taken to a fire station on East St. Paul Avenue and given a one-sided semblance of a trial. Clark was then dragged through the Third Ward and hanged from a rope tied to a pile driver.” – Carl Swanson

- Historical designation for George Marshall Clark’s lynching site moves forward after public hearing

- Public hearing to determine if George Marshall Clark’s lynching site will be added as landmark

- The lynching of George Marshall Clark in Milwaukee

- Milwaukee Notebook: An 1861 lynching in the Third Ward

Hannah Dugan