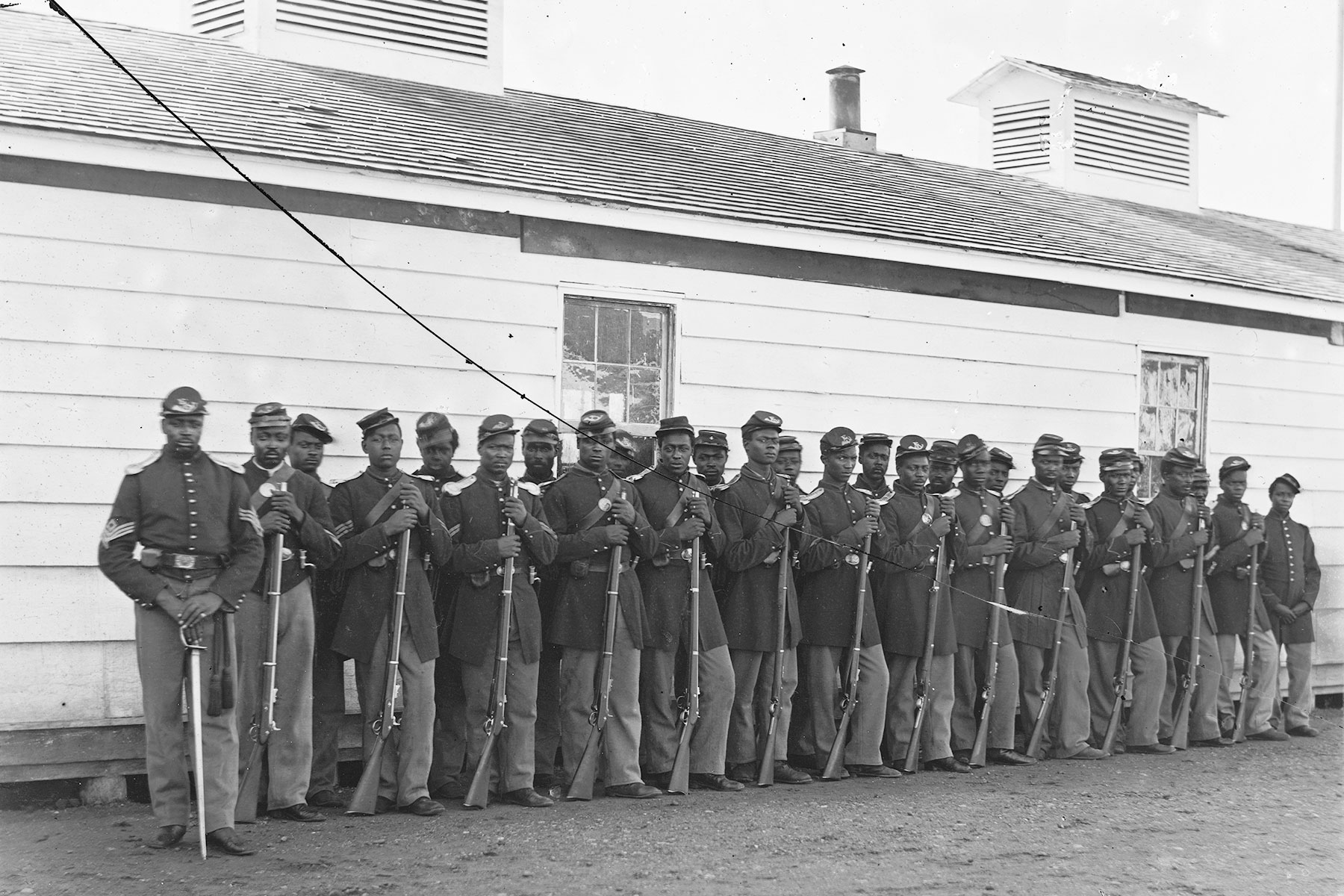

Forest Home Cemetery is the final resting place for only two Soldiers of Color who fought for Wisconsin in the Civil War.

William Reed joined Company F, 29th Infantry Regiment of the United States Colored Troops (USCT) on April 7, 1864 and followed 1750,000 African Americans into battle. Upon his death after the war, he lay in an unmarked grave for 121 years until a headstone was installed on May 30.

“We know that he served his country from April 7, 1864 until after the war ended in November 1865,” said Ricky Townsell, a re-enactment group member of Company F, USCT. “Private Reed saw the loss of over fifty percent of his comrades at the Battle of the Crater in Petersburg, Virginia. And his unit was present at Appomattox Court House when General Lee surrendered.”

A retired Army major, Townsell explained that the 13th Amendment to the Constitution is what inspired Private Reed and Men of Color to fight during our Nation’s great Civil War. The measure formally abolished slavery in America and declared that “neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.” The 13th Amendment was passed by Congress on January 31, 1865 and ratified by the States on December 6, 1865.

Members of the Company F, USCT re-enactment group formed through associations with the Milwaukee Veterans Administration (VA) Medical Center. A multi-era event called Reclaiming Our Heritage was once held annually on the VA grounds and included re-enactors from the War of 1812 to Afghanistan.

“Jack Tomlinson and Charles Wallace, who became our founding members, were going to represent the 54th Massachusetts.” explained one of Company F’s founding members, Carla Brockman. “Laura Rinaldi, who was a member of Friends of Reclaiming Our Heritage (FOROH), told Jack and Charles that we had a Black Civil War solider buried in our cemetery, Essex Roach, Company I, 118th USCT. She also told them about Company F, which interested Jack and Charles enough to start their research.”

Noted historians Tom Ludka and Margaret Berres located the unmarked grave site of Private Reed, using the same process they have for more than 160 veterans from the Civil War.

“What we do is reference the nearby headstones that are marked and find those coordinates in the section,” said Berres. “Because the lot maps at Forest Home are detailed and to scale, we can locate the unmarked graves from the ones that are listed and find exactly where the soldier is buried. It didn’t take us long to find Private Reed’s location.”

Carla Brockman originally contacted Ludka while he still a Veteran Service Officer at Waukesha County Veterans Services, and asked him about the possibility of finding the burial place for William Reed. His unmarked grave was found section D at Forest Home. Brockman was notified about the discovery and situation, then informed that Ludka and Berres managed a program where they can get headstones for unmarked military graves.

The government began offering headstones at no charge for military veterans after 1873, but many men died before that date or their families were unaware of the federal service. Members of the Company F re-enactment group raised the $275 fee to install the grave marker, which was dedicated on Memorial Day.

It has been reported that Private Reed was buried in the black section of Forest Home Cemetery, but that statement was factually incorrect because no area was ever designated for that purpose. Section D was set aside for single individuals without families. It was also among other sections used for Milwaukee County burials of poor individuals, or mass burials like the cholera epidemic that hit the young city in 1849 and filled up available graveyards.

While Forest Home still has a land inventory for another century of burials, many open spaces are actually paupers graves, where there was no funds for a headstone. At the time of Private Reed’s death in 1895, the African American population of Milwaukee was too small to necessitate racial segregation at the area’s predominate cemetery. For example, the famous African-American civil rights leader Ezekiel Gillespie can be found in Section 31, within close proximity to founder of Walker’s Point, George H. Walker.

Research also found that Reed’s wife Nancy, who had survived on the pension of a veteran’s widow, was placed to rest in an unmarked grave in Section E. The separate location and lack of a marker was a common financial problem for any citizen from that era.

The other Colored Civil War veteran buried at Forest home fought with a Pennsylvania unit and was not part of the Milwaukee Company. Ludka noted that some USCT officers were buried at the cemetery. However, only white men were allowed to be officers of colored units.

“We represent the only black unit from Milwaukee and Southeastern Wisconsin that actually fought in the Civil War,” said Townsell. “We know that this American hero laid in an unmarked grave for over 100 years. That is why we are here, to finally give Private Reed the long overdue military honors he deserved as an American fighting man.”

The 29th Regiment, United States Colored Infantry was originally known as the 29th Regiment Infantry, United States Colored Troops. It was formed in Illinois to served in the Union Army. Company F was designated with troops from the State of Wisconsin and Milwaukee County. Private Reed was one of 75 members of the original Company F, 29th Infantry, USCT.