The pride of the American legal profession visited Milwaukee only once, and for merely a day.

Illinois lawyer Abraham Lincoln came to Milwaukee not at the behest of Wisconsin bar colleagues, [1] but rather at the behest of the State Agricultural Society of Wisconsin. He came not as a skilled litigator, but rather as a celebrity. And he did not disappoint. He came to the 1859 version of the Wisconsin State Fair, during which he earned some speaker’s fees and gained some political friends. Within five months, he headed to New York to deliver his career-changing Cooper Union Speech, and within 18 months he was off to Washington, D.C., to deliver his first presidential inaugural address. But first he came to Milwaukee to talk about agriculture, a topic dear to Wisconsin. This article takes a brief look at the occasion of Lincoln’s day in Milwaukee and the message his speech delivered.

Context

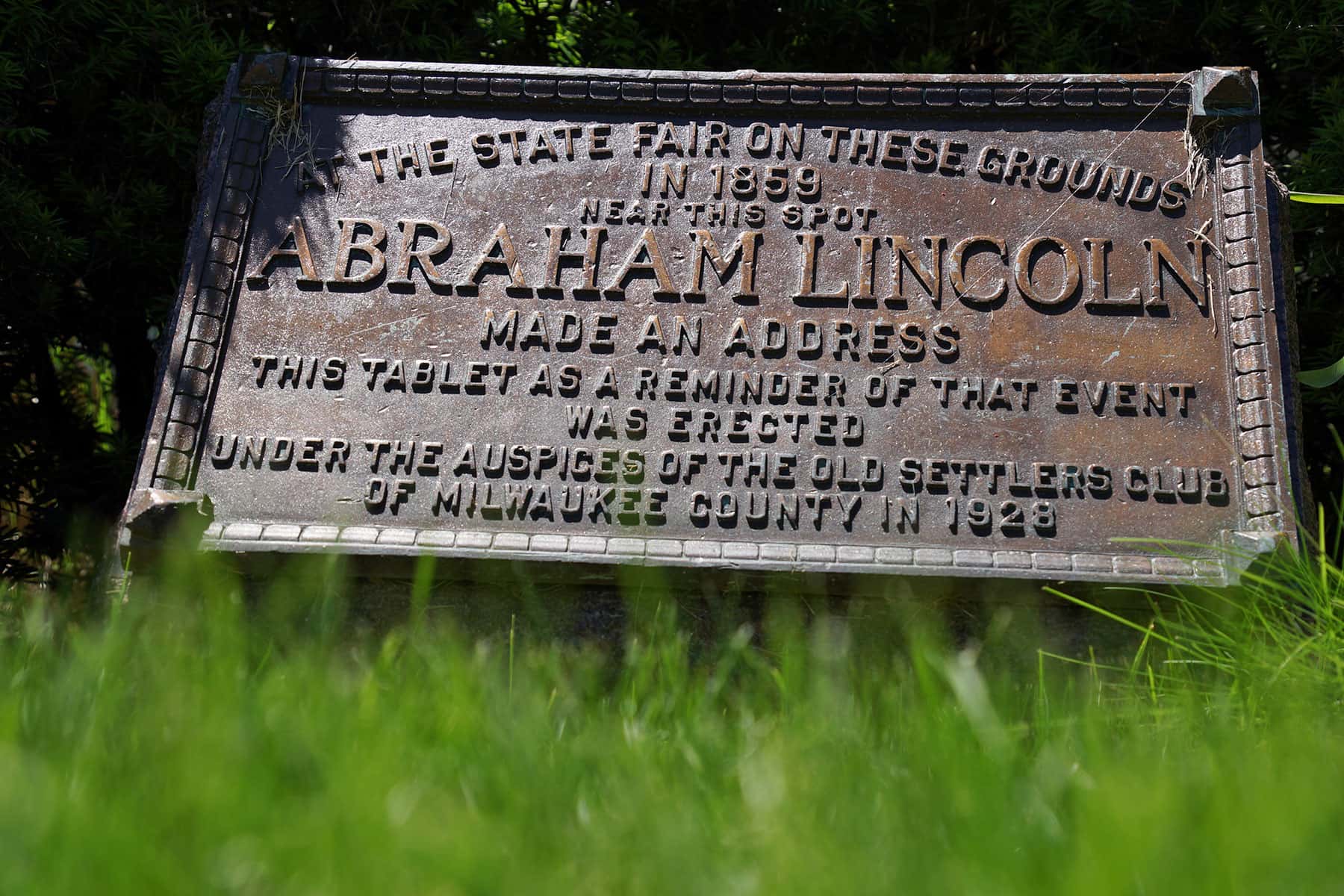

It is documented that Lincoln was in Wisconsin twice. He fought in the Blackhawk War as a captain in 1832 in the Janesville area; and he delivered a speech at the Wisconsin State Fair in Milwaukee in 1859, traveling the next two days to Beloit and Janesville for political purposes. [2]

The current records of Lincoln’s Milwaukee visit contain the post facto mythology that seems typically to follow Lincoln. Different accounts about the details surrounding his visits were recorded throughout the years by various Wisconsinites who attended the fair and other gatherings. Local newspaper articles, some as late as 1932, appeared at various intervals for years. The interviewees’ accounts are inconsistent and often self-promoting, and therefore demonstrate the historical unreliability of memory and memoirs.

The most reliable account of the future president’s Milwaukee visit ends up being, by default, the most consistently reported facts. The first and foremost verifiable fact about the speech is the content of the speech itself. Lincoln wrote the speech in his own hand. In addition, the speech was reprinted in the Milwaukee Sentinel the day after its delivery [3]; in the “Transactions of the Agricultural Society of Wisconsin (1858-1859),” in the Wisconsin Farmer and Northwestern Cultivator (November, 1859); and in a compilation of Lincoln’s works, published in 1907. While the Milwaukee Sentinel did not actually cover the speech, the Wisconsin Pinery of Stevens Point did. Henry Bleyer, the Pinery’s representative, who received the manuscript copy of the speech from Lincoln, reprinted it in an article entitled “Old Abe.” The newspaper’s comments included the following:

Lincoln delivered a short address which he had nicely written out, folded in the Wisconsin, and tucked away under his left arm, when first I saw him. His heart and other internal arrangements are a long way from his head. He looks as if he was made for wading in deep water. He looks like an open-hearted, honest man who has grown sharp in fighting knaves. His face is swarthy and filled with very deep, long thought-wrinkles. He inspires confidence. His voice is not heavy, but has a clean trumpet tone that can be heard an immense distance. He thrust a stiletto into Hammond’s “mud sill” theory. It did not please everybody, I suppose, and therefore it was something positive and good.

The 1859 Wisconsin State Fair

The ninth year of State Fair of Wisconsin was sponsored by the Wisconsin Agricultural Society, a group led by prominent Wisconsinites whose approach to agriculture was largely academic rather than practical husbandry. [4] The Society’s interests reflected the emerging scientific study of agriculture later promoted by the state’s college system. For nearly a decade the fair had been held in different Wisconsin cities; it would continue its traveling nature until 1892, when it finally settled in its permanent and current location in West Allis.

The enormous Cold Spring Race Track became the location of the 1859 State Fair. [5] In the center of the grounds, small buildings and the judges’ stand were sited on two Indian mounds. 100 stalls for cattle were sited on the south side of the grounds, and refreshment stands were sited on the west side, strategically distanced from the animals. The grounds included a number of other buildings for agricultural machinery; a grandstand for 500 people; a racetrack for horse competitions; and tents for exhibits of horticulture, agriculture, and dairy products. The grounds were surrounded by a temporarily constructed high board fence. The Menomonee River hosted the fireman’s tournament and the regatta contests. The events were held from September 26 to September 30. The featured event of the fair was not Lincoln’s speech; it was the plowing match. [6] Over 15,000 persons attended the fair (equaling one-third of the city’s population), and about 1,400 entries were judged in the various competitions.

The Invitation to the Fair

Lincoln spoke on the final day of the fair. He was invited to be a “draw” to the fair, in particular because of his celebrity following his impressive performance during the 1858 Lincoln-Douglas debates. For years Lincoln had been delivering speeches on a variety of subjects to hone his skills and increase his public presence. A prominent speech in his repertoire, entitled “Discoveries and Inventions,” demonstrated his ability and agility with subject matters beyond his professional field. The fair organizers specifically, and perhaps boldly, asked him to give an address about agriculture.

While various people claim credit for Lincoln’s presence at the fair, letters were discovered in 1921 establishing David J. Powers, a farmer in Madison, Society Secretary, and editor of the Wisconsin Farmer, as the man who procured the celebrity speaker. [7] Powers wrote an unanswered letter in July 1859 and followed with a second letter a few weeks later. Lincoln responded:

Dear Sir: —Reaching home after an absence nine days I find yours of the twelfth. I have also received that of Jul 27; and, to be plain, I disliked to decline the honor you tendered me. Two difficulties were in the way—first, I could not well spare the time from the courts; and secondly, I had no address of the sort prepared and could scarcely spare the time to prepare one; and I was waiting, before answering yours, to determine whether these difficulties could be surmounted. I will write you definitely on the first day of September, if you can safely delay so long. Yours very truly, A. LINCOLN

Powers immediately understood that Lincoln was asking about a speaker’s fee. And due to recent circumstances, Lincoln had to so inquire. His rising political and public star had taken him away from his lucrative practice. He had lost the Illinois senatorial race (although he won the debates), and his Republican colleagues had expected him to replenish the coffers depleted by his campaign. Powers immediately responded that Lincoln would receive $100.00 for the engagement, and the Illinois lawyer immediately accepted the invitation. He would speak on September 30, the final day of the fair.

The Speech

The hospitality upon Lincoln’s September 29 arrival was less than gracious. His accommodations at the Newhall House were botched, reportedly resulting in a sheet being hung across a public space to create a “room” for privacy. In addition, his escorts were disorganized, such that Lincoln’s scheduled 10:00 a.m. speech did not happen until noon. A platform wagon, procured as a stage for the speech, was set under a tree. Of course, the tree provided shade from the hot, noonday sun, but Lincoln’s height on the tree-covered “stage” posed a different comfort concern. [8] Hundreds were in attendance.

It is somewhat ironic that Lincoln spoke about agriculture because he loathed farming. His father, Thomas Lincoln, had cleared land for farming three times in Kentucky, he moved the family to Indiana in 1816 to clear land to farm, and moved to Illinois in 1830 to yet again clear land for farming. Under the cultural and economic norms of the time, all Lincoln’s work and wages were obligated to his father until he was 21. [9] He was a decidedly reluctant and disinterested farmer, although his famous rail splitting was honed by the farm fences he helped construct. He left farming and his father as soon as he could, in 1830, each settling in different places in Illinois. But his State Fair speech is filled with husbandry language; he imparted his knowledge about farming, despite himself.

Superficially, the speech appears deliberately not to be political, avoiding the subject of slavery that had dominated the previous year’s Senatorial debates. However, the speech does reveal insights into Lincoln’s view of economics, labor, and the individual in society. And it includes ashes of lines he retooled and integrated in later, more significant speeches.

Lincoln began his 14-page speech with a page’s worth of disclaimers about his ignorance of the topic, and a celebration of agricultural fairs as means for sharing ideas and community and bringing together the agricultural and industrial arts. He compared fairs to the Patent Clause in the Constitution: both stimulate discovery and invention into extraordinary activity.

The famous lawyer then launched into the substance of his speech, encompassing a wide range of agricultural topics. He began with detailed statistical information about farm yields and pushing the soil to “up to something near its full capacity.” He argued that the price a farmer would have to pay for the increased crop was “more labor to the acre but not to the bushel.” More intensive, smaller farming created efficiencies and yield that allowed for savings by buying less land, yet getting more yield. He called this effect “thorough farming.” Intensely cultivated small farms, rather than larger ones, made the best economic sense. Lincoln then described the net effect on farmers following thorough farming principles: a full crop with less labor and fatigue results in more pride and success.

“The ambition of broad acres leads to poor farming even with men of energy.” So mammoth farms were undesirable; they worked against the “family farm” and against one‘s independence. Lincoln, economically, was trying to convince the farmers to adjust to the end of the country’s geographical expansion.

Immediately after discussing large-scale agriculture as economically unfeasible, Lincoln continued by urging mechanization. He launched into a longer discussion about a steam plow because “steam had conquered the face of nature” with steamboats and trains. But he then entered into a discussion about steam plowing’s technical difficulties, and concluded with reservations about the whole idea.

After this portion of the speech Lincoln launched into a long discussion about labor and capital. He stated that the “the world is agreed that labor is the source from which human wants are mainly supplied,” but from this point “men immediately diverge.” He described the “mud sill theory” that no one labors unless somebody else owning capital induces him to do so.“That whomever is once a hired laborer is fatally fixed in that condition for life and thence his condition is as bad as or worse than a slave.” Then he asserted the opposing view: that there is no such labor/capital relationship as the mud sill theory states, and that labor is superior to capital. He characterized the theory of “free labor” as being companioned with education, and therefore opposed the mud sill theory. He asserted that labor and capital are not incompatible.

Lincoln, a true politician, stated that he had:

so far stated the opposite theories of “Mud Sill” and “Free Labor” without declaring any preference of my own between them. On an occasion like this I ought not to declare any. I suppose, however, I shall not be mistaken, in assuming as a fact, that the people of Wisconsin prefer free labor, with its natural companion, education.

Though not recorded, such a statement no doubt was a crowd-pleaser.

Lincoln concluded by stating that “men deriving a comfortable subsistence from the small area of soil can never be the victim of oppression.” He ended with the inspiring words:

Let us hope rather that by the best cultivation of the physical world beneath and around us and the intellectual and moral world within us we shall secure an individual, social and political prosperity and happiness whose course shall be onward and upward and which, while the earth endures shall not pass away.

While ostensibly his speech is apolitical, it actually is not, according to Gabor Boritt. [10] The premises of his economic statements and labor analysis reflect the same moral bases and opinions regarding slavery. The radicals of his party denounced slavery on purely moral grounds and the conservatives denounced it on grounds of economics. Because Lincoln’s ideas united these extremes, he was in the very center of his party—the perfect compromise choice for a presidential nominee. The speech lasted one hour.

Post Speech

Afterwards, Lincoln was feted by the Wisconsin Horticultural Society with a fabulous lunch in front of an elaborate wall of live foliage. He toured the grounds and exhibits, watched the plow contest and congratulated the winner, and tried his hand unsuccessfully at a sledgehammer contest. He returned to the Newhall House for a tea with dignitaries who prevailed upon him for a speech on “The Irrepressible Conflict.” He left Milwaukee the next day for political gatherings and speeches in Beloit and Janesville. Throughout the rest of the year, Lincoln traveled east for more engagements, increasing his presence and, as it turned out, the prospects for his nomination and presidential election.

Post Script

In 1862 this attorney, who escaped a life of agriculture and husbandry as soon as he could, signed legislation creating the United States Department of Agriculture.

This essay was originally published as Lawyer Lincoln’s Only Visit to Milwaukee: the 1859 Speech at the Wisconsin State Fair in the MBA Messenger • Summer 2010 • Volume 2. It is presented here with the generous permission of Hannah C. Dugan.

© Image

Lee Matz