Vietnam has been one of the central influences of my life, growing up in its aftermath. The war had a profound effect on my childhood. From when I first lived with family in Milwaukee, while my father served his tour there, to even now as an older adult. There seems to be no escape from its gravitational pull. Experiences continue to reconnect me with memories from years ago.

Over the past few years I have reported on and photographed events that were attended by many Milwaukee veterans, particularly from the Vietnam War era. It has been a privilege to know many of these individuals. With a swelling of pride and patriotism, it is easy for the public to revere those veterans with a type of celebrity status.

I struggle with finding the correct adjectives to summarize who they are, while at the same time being mindful of their deep humility. These heroes have yearned for acceptance by the American society, but are still unwilling to use the word hero to describe themselves.

Perhaps the greatest honor I have is to call them each a friend, which is an undervalued word thanks to Facebook. There is just no way to articulate the healing and love given by these individuals, to me and everyone they meet. Their true celebrity is a simple and honest gift of kindness.

Joe F. Campbell is one of these spiritual beings, who walks around in the fragile form of an aging human body.

Joe contacted me recently about a special event. Kim Phúc, the woman who will be forever immortalized as the “Napalm Girl” from the famous Vietnam War photograph, was coming to Milwaukee to meet with him and other veterans who I knew. I was invited to join them, both professionally as a photojournalist and personally as the son of a Vietnam veteran. I had just written an article about revisiting my 1997 experience of a trip to Saigon, and saw the timing as no coincidence.

In talking with Joe about the background of the visit by Kim Phúc, he shared his own story. It was a remarkable and interconnected journey with Kim’s, and in a way with my own. Which is why sharing Joe’s words in his own voice is important, for context and depth.

This is the transcribed version of that conversation with Joe F. Campbell. The accompanying images were taken during the June 10 lunch with Kim Phúc, and from past events in Milwaukee. Included are also photographs that Joe took in Vietnam. The Big Boy pictures are historical references.

Joe F. Campbell reflects on Vietnam and meeting Kim Phúc

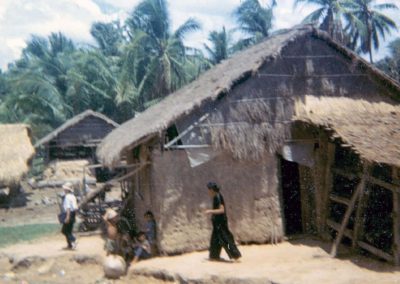

I was serving with the 1st Logistical Command in Củ Chi, Vietnam, which was home to the 25th Infantry Division. My duties there were to support the 25th Infantry with maintenance of the artillery, the 155mm and 175mm howitzers, as well as trucks and tanks. One morning the company commander mentioned that they needed volunteers to go out with the medical civic action team. That was comprised of doctors and nurses and medics, who go out to small villages in various areas. The goal was to assist the villagers with basic medical needs and help with hygiene issues. It was an effort to show the local people that we were good Americans, and we wanted to win their hearts and minds.

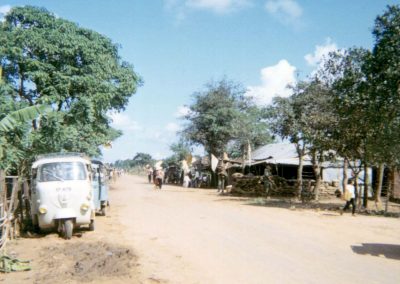

My job kept me working 12 hours a day, 7 days a week. But occasionally something would come up where volunteers were needed, and I liked to join those missions. So that was how I ended up in the village of Trảng Bàng, which didn’t mean a whole lot at the time. Other than we knew it was an area that was relatively safe during the day, but at night it was terrible and had a lot of Viet Cong activity.

So I volunteered for guard duty for the medical team with a couple other guys, and we went out to Trảng Bàng. We were there for about an 8 hour stretch from early morning to afternoon, until the doctors and medics felt it was time to go back. No one wanted to travel in the dark, it was too dangerous.

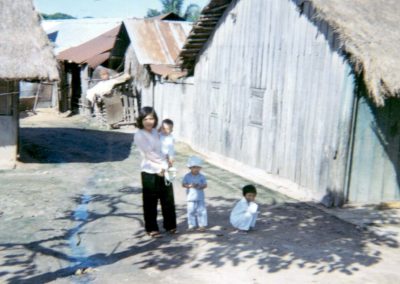

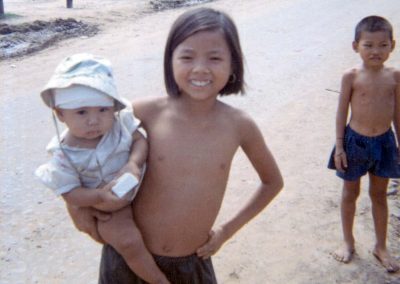

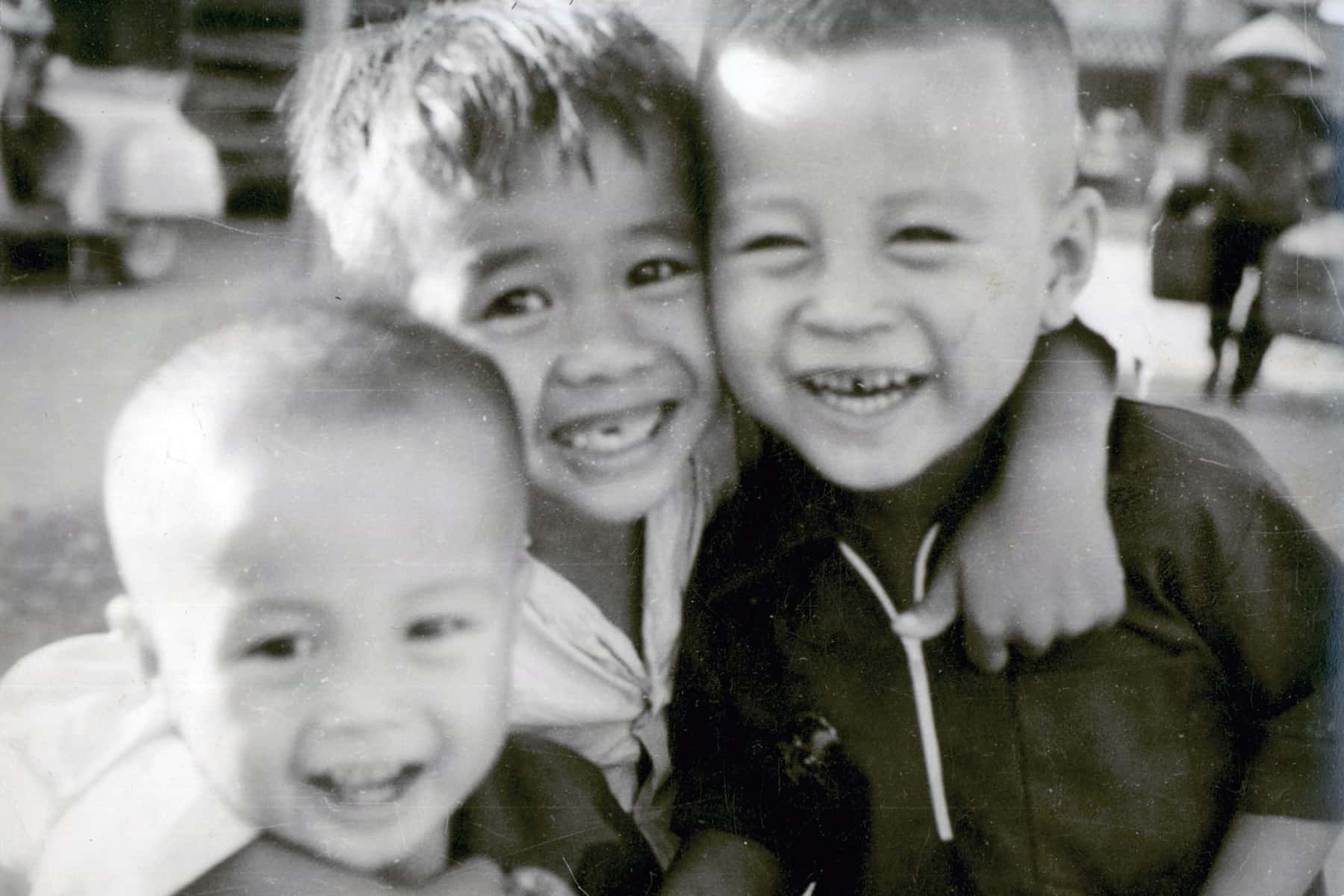

When we got there, my task was basically to keep the area safe. But all that meant was I just walked around the village with my rifle, mostly to be present. I brought my camera and took some pictures of the kids and the villagers there. The place was a very small cluster of huts, with cows and chickens and pigs that also lived in those huts, along with grandma and grandpa together.

And I saw these beautiful kids playing. One little girl carried her baby brother, with a bar of soap and a washing dish. They were just so happy. Even though we didn’t speak much Vietnamese and they didn’t speak much English, we communicated a lot with smiles. On those type of trips if I had any hard candy with me, I would give it to the kids.

So I took all these pictures while I was there, about 10 or 12 of the village and some of the kids, and never gave much thought to it. After I had them processed, I wrote on the back of the photographs that they were taken in Trảng Bàng in July of 1967, a place with about 150 villagers. They didn’t get ruined, because I sent them home to my older sister Terry and she kept them.

I forgot I even sent them, and it was many years later when there was an article in a magazine about the “Napalm Girl,” as they called the young child in the famous picture who survived when her village got napalmed. I had seen the picture and heard about it years before on the news, because it was such a disastrous and terrible thing. I can never forget seeing this poor girl, running naked down the road and knowing that napalm had been accidentally dropped in her village. It burned her skin off with her clothes.

I was not there in June 1972, but my sister sent me the pictures after the article came out. I looked on the back of them and saw where I had written Trảng Bàng. The magazine article about the napalm incident said it happened in Trảng Bàng, and I realized that I had been to that village 5 years earlier – before the incident – in 1967.

Then around spring of 2004 I heard this little girl, Kim Phúc, was coming to Milwaukee. She was all grown up and sharing her life journey as part of a lecture series. It was hosted by the Marcus Center, and would have one famous person a month for a few month called “From the Heart.” She was going to be a keynote speaker and give a presentation, and I just had to meet her.

I wanted to hear about her story, about her life after she was terribly burned, and show her my photos from her village.

So I reached out to my friend Bob Curry, who founded Dryhootch and had a daughter in the news media, and I asked for help to try and attend Kim’s speech at the Marcus Center – because the event was for women only. Eventually I got a ticket and they put me in a great seat near the podium, but kind of by myself.

I gave my photographs to the security staff and asked if they would share them with Kim to see if she knew any of the people. She was 9 years old in 1972 when the incident happened, which meant she was almost 5 or so when I there. Most the kids in my photos were under 10.

The presentation Kim gave for the program was wonderful, with videos and pictures, and her story of faith, health, happiness, peace, and love – it was a very inspiring talk. She answered questions from the audience, that they had written before the program started, and she got a standing ovation.

Then before she left the podium, she said there was a Vietnam veteran that was in the audience and she wanted to meet him. So security came and got me and took me to a private room with her. Kim spoke really good English, and I just embraced her and told her how much we fought for her life, and how many of my brothers gave their life to protect her. And while it was terrible what happened to her, and all the scars and memories she carried, I was so happy that she was free and able to live a new life. Our conversation continued her message of hope and faith and respect and love, and so we had just a wonderful meeting.

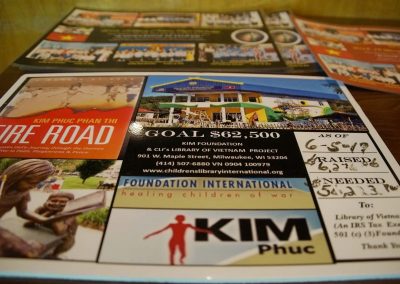

My friend Chuck Theusch was with the Americal Division around 1967-68 as combat infantrymen, and had a farm back here in Wisconsin when he got out of the service. He started Children’s Library International to build Peace Libraries all over in Vietnam about 15 years ago. He would get various sponsors, some of them were Vietnam vets that had started businesses and supported his effort. He got the Communist government of Vietnam to approve his construction of the Peace Libraries, which had a standard design for cost and look, and now they are all over Vietnam in the north and south, and in Laos and Cambodia.

Chuck told me that Kim Phúc was coming to Wisconsin to raise funds to build a Peace Library in Trảng Bàng, in honor of her cousins who died that day. The Vietnamese government used her for many years as a poster child of the terrible things the United States did in the war, while she was being treated for her injuries. She was not allowed back in Vietnam once she sought asylum in Canada, when she was traveling to Cuba. She was coming back from her honeymoon trip to Russia, with a refueling stop in Canada, when they managed to leave the plane and escape to freedom. But she was cut off from her family in Vietnam.

Chuck goes over to Vietnam every year for a couple months, and he has been communicating with Kim for the past few years. She started the Kim Foundation International to help the children from the war who struggle with their physical wounds, and one of the programs helps with the removal of landmines. There are still landmines all over the place, and villagers and farmers come across them all these years later and get blown up.

Kim has been a real activist for peace, and her connection with Chuck is how she is working to get a Library in Trảng Bàng. The lunch in Milwaukee is a special meeting with area veterans who served in Vietnam and near the area where she lived.

I spent Christmas in Phước Vĩnh. We had a base there north of Saigon and near the Cambodian border. My sister would send me hard handy, and I’d give it to kids when I saw them in villages. So, my company commander said I could take a jeep into the village and bring back as many kids as I could fit into a jeep. I brought something like 25 kids, all piled in and hanging on. We had this cook out with my team, and kids had hot dogs and beans. They loved everything, and having them really made it Christmas for us. It did so much for me and my team, to lift our spirits being away from home. We were able to give ourselves, our food, our friendship, our family, and our fun to these kids, so it was a really wonderful day.

That is why I have an old Christmas tree in my house and keep it up. Whenever I get some Vietnam blues – and think poor me, I didn’t get treated right when I got home or whatever – all that goes out the door when I look at the tree. I thank God, and feel so blessed to look back at myself at 19 years old. I was able to bring joy and happiness not only to those kids, but also to ourselves. It’s a wonderful memory that I hold very dearly to this day.

We always hear about the horrors of the war in Vietnam, and about veterans coming home and being mistreated, which unfortunately is true. But at the time, we always felt so isolated because news took so long to reach us. If we wrote a letter home, it would take 3 weeks at least to get an answer, and by then it was hard to remember what the question had been.

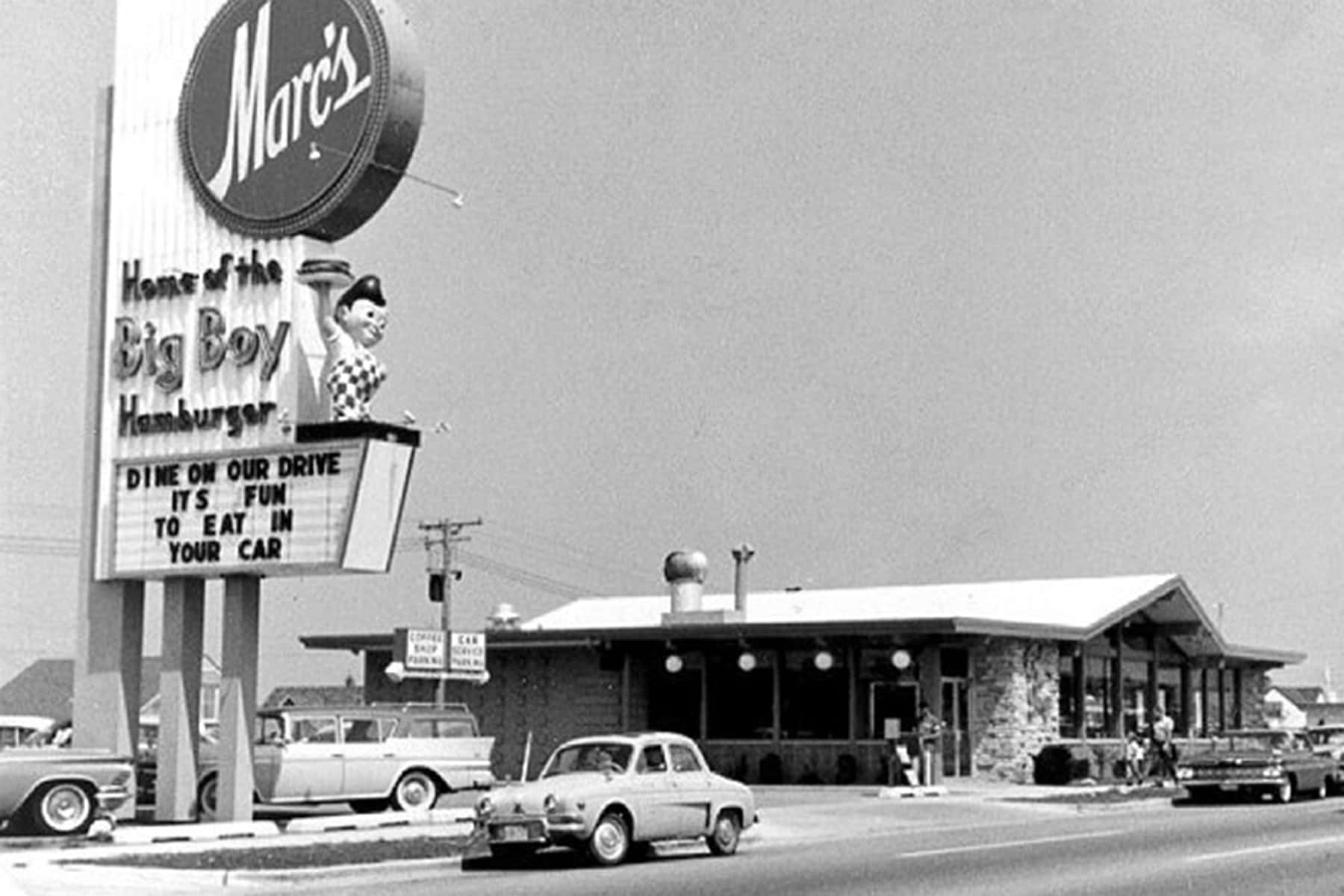

So during my last assignment, one of my best friends with me in Phước Vĩnh was from Wheaton, Illinois, and I was from nearby St. Charles. One time when we talking, he asked if I ever went to that Big Boy restaurant in Wheaton, and I said I ate there all the time because it was one of my favorites. I just loved that place, because we could go at night and all these different hot rod cars that would be there.

So I’m out on a mission in Vietnam, and I’m trying to call in our position on the radio while dealing with driving the jeep. I’m talking to my friend on the radio and he asks while I’m out if I could stop by to pick up a Big Boy, an order of onion rings, with a chocolate malt and Coke chaser. And I just could not believe it, I started laughing my head off.

We played that game back and forth a number of times, when we least expected it. When my tour was over in February of 1968 and I came back to the States, my high school sweetheart – who I was engaged to, skipped her college classes that day to be with me. The first place I stopped at on the way home was a Big Boy. I ate in Wheaton, Illinois and ordered a Big Boy, an order of onion rings, with a chocolate malt and Coke chaser.

I just smiled and prayed that my good friend Bill, who was still over there, would come home safe – which he did. We did our job and we did it well, and we can never forget the ultimate sacrifice so many of our brothers made for us. And they relied on us to save them too.

It was things like that that lifted my spirits, and I even have Big Boy posters in my house. It was something that replaced the terrible things we lived, and saw, and helped change the focus.

- Inconvenient Images: How pictures teach us to see the world for what it is

- Milwaukee’s hometown Air Wing kicks off Armed Forces Week with aerial refueling flight

- William Pelkofer: Wisconsin Air National Guardsman takes home-grown path for pilot training

- Dawn of the Red Arrow: Documentary details birth of Wisconsin’s 32nd Division in World War I

- Bay View students revive Lance P. Sijan Memorial Scholarship as example of leadership, love, and honor

- Brewers legend Robin Yount recognized for years of citizen involvement in helping the Armed Forces

- Gold star family, George Banda, and Iwo Jima veterans recognized with Sijan award for valor

- Veterans Day Parade 2018 honors Milwaukee’s Red Arrow Division for its WWI service

- Milwaukee Notebook: Red Arrow, the Park that Moved

- Janine Sijan Rozina: A story not of war but the spirit of love

- “Sijan” and Chip Duncan’s “The First Patient” among world premieres at Milwaukee Film Festival

- Fellow POWs honor their fallen brother at Sijan Plaza dedication

- Photo Essay: Preview of Sijan Plaza and memorials of honor

- Photo Essay: An example of courage installed at Mitchell Airport

- Ben Domian: a life influenced by family and Lance Sijan

- Vietnam combat medic George Banda honored at tribute to Latino veterans

- Lynn Novick: A discussion about her Vietnam War film on Veterans Day

- The irony of visiting heroes at Arlington, the former home of a national traitor

- Photo Essay: Seeing the Nation’s Capital with Milwaukee Eyes

- George Banda: Honoring lost friends in vigil to Vietnam veterans at The Wall

- Maya Lin: Ceremony marks 35th anniversary of Vietnam Memorial’s healing power

- George Banda: The Humble Hero

- Audio: An American story from Mexico to Vietnam

- Purple Heart Day honors Milwaukee’s wounded veterans

- Photo Essay: Milwaukee’s 54th Annual Veterans Day Parade salutes hometown heroes

- Online patriots too lazy to honor troops by actually attending Veterans Day Parade

- Thank You, Canada, for loving Milwaukee Veterans

- Aerial demonstration squadrons announced for 2019 Air & Water Show

- Flying with the Golden Knights during the Milwaukee Air & Water Show

- Air & Water Show 2018 performances prepared and waited for weather to clear

- Exclusive: 360° view of skydive at 2,000 feet over Milwaukee with precision landing

- Video: Army’s elite parachute demonstration team descends over lakefront

- Airshow sees Army Parachute Team descend through the atmosphere

- Photo Essay: Golden Knights Practice Jump attempt at 2,000 feet

- Photo Essay: Golden Knights Precision Landing from 12,500 feet

- Photo Essay: Free-falling with the Golden Knights Demonstration Team

- Video: U.S. Army Golden Knights parachute into Milwaukee Airshow

Lee Matz, Nick Ut, and Joe F. Campbell