In early September, the following question appeared in our message box on the Overpass Light Brigade (OLB) Facebook page: “Do you have any plans of going out to North Dakota to support NO DAPL? It would be so awesome if you do.”

We were already watching closely, and frequently posting on our social media accounts about the growing indigenous movement centered on the Standing Rock Sioux’s stance against the Dakota Access Pipeline. We knew the fight there was reminiscent to fights we had supported here in Wisconsin, including a recent battle against an iron mine in the Penokee Hills.

Our own city of Milwaukee, dubbed “Water City USA” was finally coming to grips with the fact that its water supply was largely tainted with lead, leading to Mayor Barrett calling for the installation of filters on all city taps. We had not really seriously considered making the 14 hour road trip to Canon Ball, but why not? History was happening, and we felt called to witness it.

I dialed the other members of the OLB core group, and several days later we were on the road from Milwaukee for a Labor Day weekend visit. We set out for the Oceti Sakowin Camp in a van packed full of lighted letters, tents, and four passengers interested in seeing what the mainstream media was going out of their way to not report.

This account captures some of those moments we were witness to.

We arrived at the camp around noon on Friday, where we proceeded to the “Check-In” tent located in the main community gathering. We felt quite disoriented at first, and wandered through this hub of camp activity, complete with a kitchen, school, and supply tent, trying to take it all in.

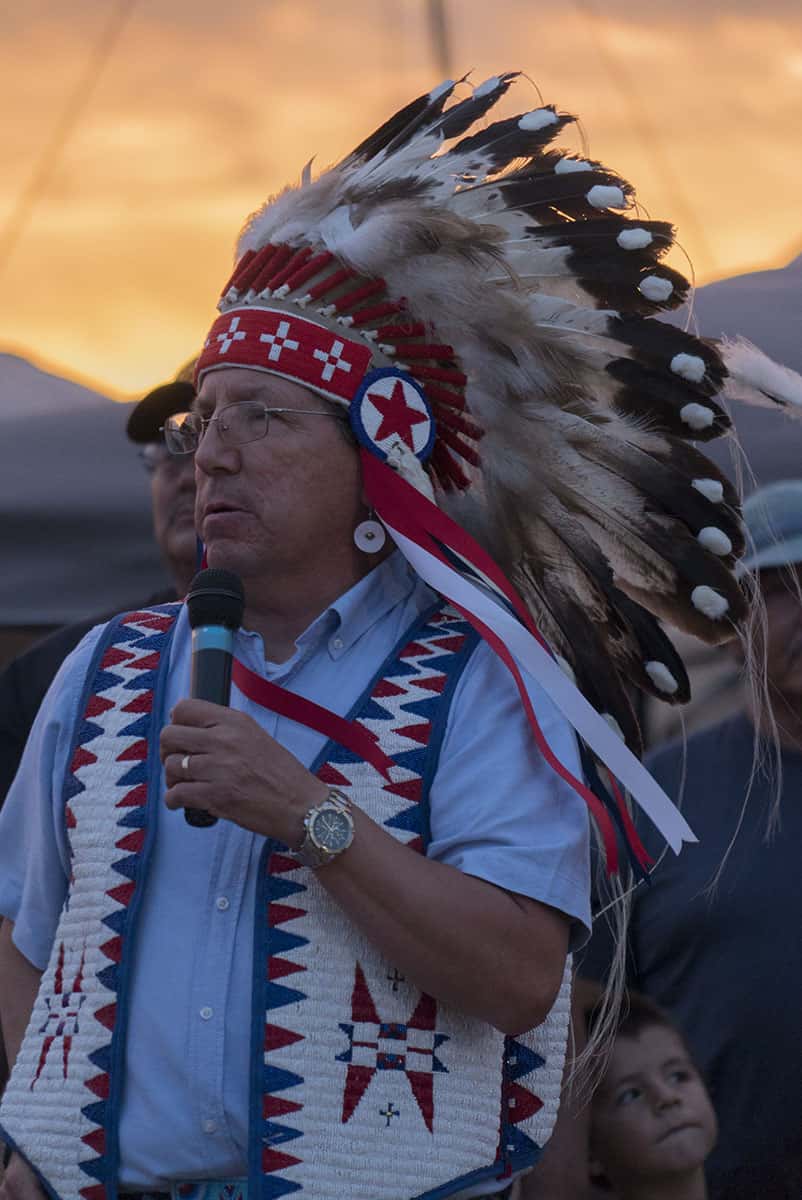

We watched in awe as groups of Indigenous Nations arrived in the camp’s northern entrance. They entered in a ceremonial procession, down the dusty dirt road lined with flags planted by each nation upon arrival, as what the folks in camp called “The Avenue of Nations.” By the end of the weekend, there were over two hundred nations represented in camp, and that number has continued to grow.

Each delegation arrived to a welcome ceremony, where they used the community space to speak, dance, drum, or greet the camp in any way that fit the tribe’s traditions and culture. At the completion, the delegation lined up and everyone present at the community space shook hands and introduced themselves to the new arrivals.

After checking in with security and reading the protocol for guests in the camp, we set up our tents. It was suggested that we approach the camp’s elders about the possibility of doing lighted actions at nightfall. We submitted a brief proposal for the Light Brigade actions we hoped to do in support of the rapidly growing resistance movement. After some discussion, we received permission with the suggestion that young people in the camp help hold the first message.

We held two messages: “PROTECTORS” and “ALL NATIONS” underneath the flags of indigenous nations. As is often the case with Light Brigade actions, many of those gathered were captivated by the magic of the lighted letters, and pulled out their phones to capture the moment.

Instead of calling it a night, a friend joined me in walking to the top of the camp to get some nighttime photos and video. Once there we noticed a beautiful streak of color in the sky and realized we were looking at the Northern Lights, which have deep meaning in many Indigenous cultures. It was a perfect and fitting way to end the first night at Sacred Stone, and we fell asleep to drumbeats echoing throughout the river meadow, the sound of cars and trucks arriving throughout the night, and multiple voices singing into the warm, windy darkness.

The next day, we visited the locations of the pipeline’s destructive construction site that were two and three miles up the road. It was from there that tweets and Facebook posts in the weeks leading up to our visit had captured our attention and garnered our support.

It was already hot and windy, and the sun beat down once we were out of the cottonwood trees. It was quiet at the site, and we noticed one family even venturing out onto the private property to pick flowers, but this was only the calm before the storm.

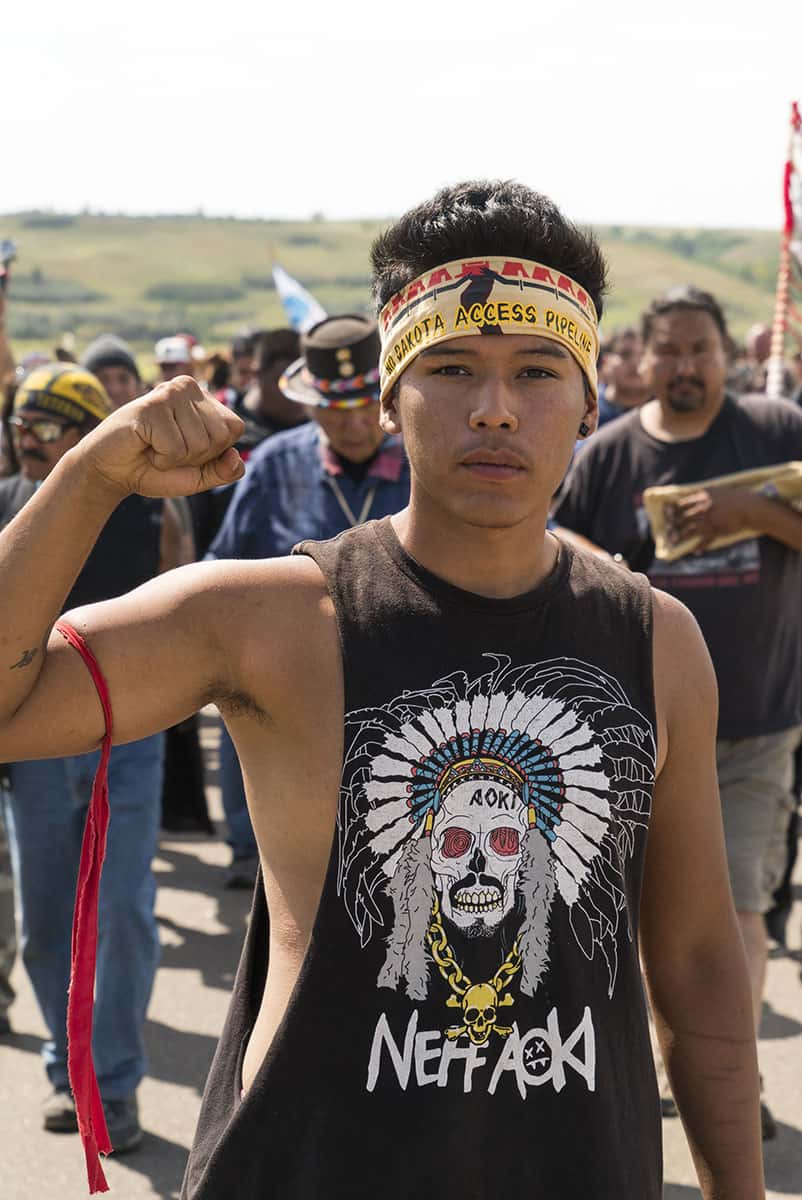

As we were driving back to Oceti Sakowin Camp we noticed an approaching march of campers, mostly Native American protectors, streaming from camp, taking command of the highway.

We didn’t follow the march all the way to the construction site entrance, but instead chose to head back to camp to catch a wonderful horsemanship event happening at Oceti Sakowin. We later learned that when this highway group arrived at the pipeline entrance, Dakota Access Pipeline workers and their private security forces with trained dogs were already in place, scraping the ground with bulldozers in spite of a judge’s order to temporarily halt all work on the land.

When the marchers arrived and tried to stop the bulldozers, security maced the Protectors on the frontline, point blank in their unflinching faces, and then released their dogs into the crowd. This action was captured by cell phones and the footage shared over social media, as well as by Amy Goodman and her news crew from Democracy Now.

Things were calmer at camp, where word of the company’s attacks had not yet circulated. We took in the beautiful community building events of horse racing and a boot race for the kids, completely oblivious to the fact that brave Protectors, just two miles away, were being violently attacked for defending the future of clean land and water.

As the Horsemanship events ended, word spread through the camp of the company’s vicious attacks, which wounded six people, including a little girl and a pregnant woman. The collective mood quickly changed from festive to restive, to anger at the continuation of colonial attitudes that allow sacred ground to be disturbed without qualm, and indigenous people to be brutalized for standing up for their culture, their rights, and the earth. At the main fire circle, everyone was reminded that peace needed to prevail, and that the camp would begin civil disobedience training in order to instill the skills of peaceful resistance in such a volatile situation.

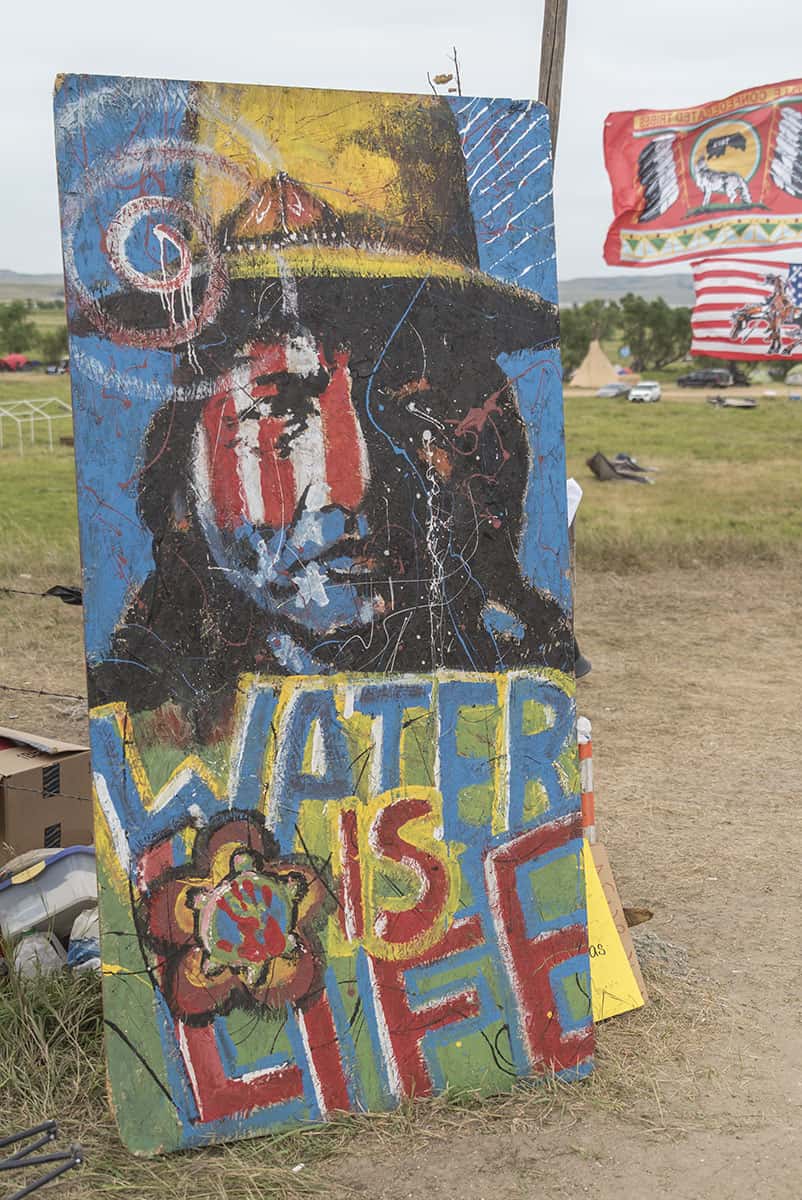

That night on our way out we transported the messages “PROTECTORS” and “MNI WICONI,” which means “Water is Life” in Lakota, and headed back to the pipeline site trailhead. A guard encampment of young Protectors was quickly forming to keep watch on the pipeline company after their illegal actions of the afternoon.

After holding the messages into the darkness of the night, we headed back to Milwaukee, but not before experiencing one last show of force by local police. They had set up massive blockades on northern and eastern roads leading into Standing Rock. We were astounding by the amount of resource they had put in place to intimidate and inconvenience people going from Bismarck down to the resistance camp.

People could leave without a problem, but they could not go in unless they come up through the Sioux Reservation to the south. That route added considerable time on to the trip.

If anyone is interested to show their support and make a visit to Standing Rock, I would recommend taking the southern route. Otherwise, at least check with people on the ground regarding the latest ridiculous roadblock. Since we left the attacks and further militarization of the police have escalated, but the Protectors remain peaceful and prayerful.

The multiple camps at Standing Rock are not going anywhere. They are only growing. This gathering of Protectors at Standing Rock gives us hope that a significant movement is forming to fight against the further colonization of oppressed peoples, and the always-escalating desecration of clean land and fresh water.

The future must be one of people and planet over profit. This is just the beginning of the fight.

Joe Brusky

Joe Brusky is a Milwaukee Public School educator of ten years, and current Social Media Organizer for the Milwaukee Teachers’ Education Association. He is a photographer and member of the Overpass Light Brigade, an activist collaborative public art project started in Milwaukee, Wisconsin in 2011. The Light Brigade Network has since expanded to over fifty chapters worldwide. His photographs have appeared in such publications as the Washington Post, Dissent Magazine, The Progressive, Labor Notes, and Rethinking Schools.

Read the article and view the photo essay that were produced as companion features for this news report.