During his life, Milwaukee attorney Frederick Winkler seemed to be everywhere. He was the Zelig of civic life in Milwaukee, the Forrest Gump of the American Civil War. And yet he is essentially unknown today.

On the anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg (July 1 through July 3, 1863) it is fitting to recall one of his most remarkable achievements: commanding Wisconsin’s famous 26th regiment at Gettysburg. [1]

The Back-Story About Winkler’s “Field Journal.”

Winkler’s life is rather well documented because he remained a celebrated “local boy” after the Civil War, an active legal practitioner and an important public servant until his death at age 83 in March 1921. Therefore a good many newspaper articles, official minutes, legislation and court records are sources of information. However, the primary source of information and insight into Winkler’s achievements is a series of battlefield letters. His time during the Civil War was well-documented by none other than himself, though available to us only via an edited version. The letters he wrote to his fiancé-turned-wife during his entire war experience from 1862 to 1865 were saved in secret.

In 1963 one of Winkler’s nine children, Louise Winkler Hitz, published the letters from her father to her mother in the book Letters of Frederick C. Winkler 1862-1865. Louise noted in the book’s forward that during the summer of 1897 (32 years after the war) all members of the household were gone for the summer except her mother, the former “Fannie Wightman of West Bend.” Fannie hired a typist. Together they typed the letters, mining “all sentiment” expressed by Winkler from what essentially were love letters, and leaving a complete diary from week to week of his experiences as a combat officer.

Even with the deletion of “all sentiment,” the letters reveal the remarkably high level of communication that occurred during the Civil War. Winkler frequently refers to and opines on the issues of the day, the various Milwaukee news and newspaper coverage that Fannie and others send to him, and the reports and editorials of the East coast newspapers that he seems to read in the field nearly contemporaneous to their publication. The book includes Winkler’s letter of engagement/permission to marry to his future father-in-law dated September 30, 1862. He left for the war on October 6, 1862; he returned to Milwaukee several times during the war including in 1864 for his marriage to Fannie. But we’re ahead of the story.

Brief Pre-War Biography: Armed by the Milwaukee Bar

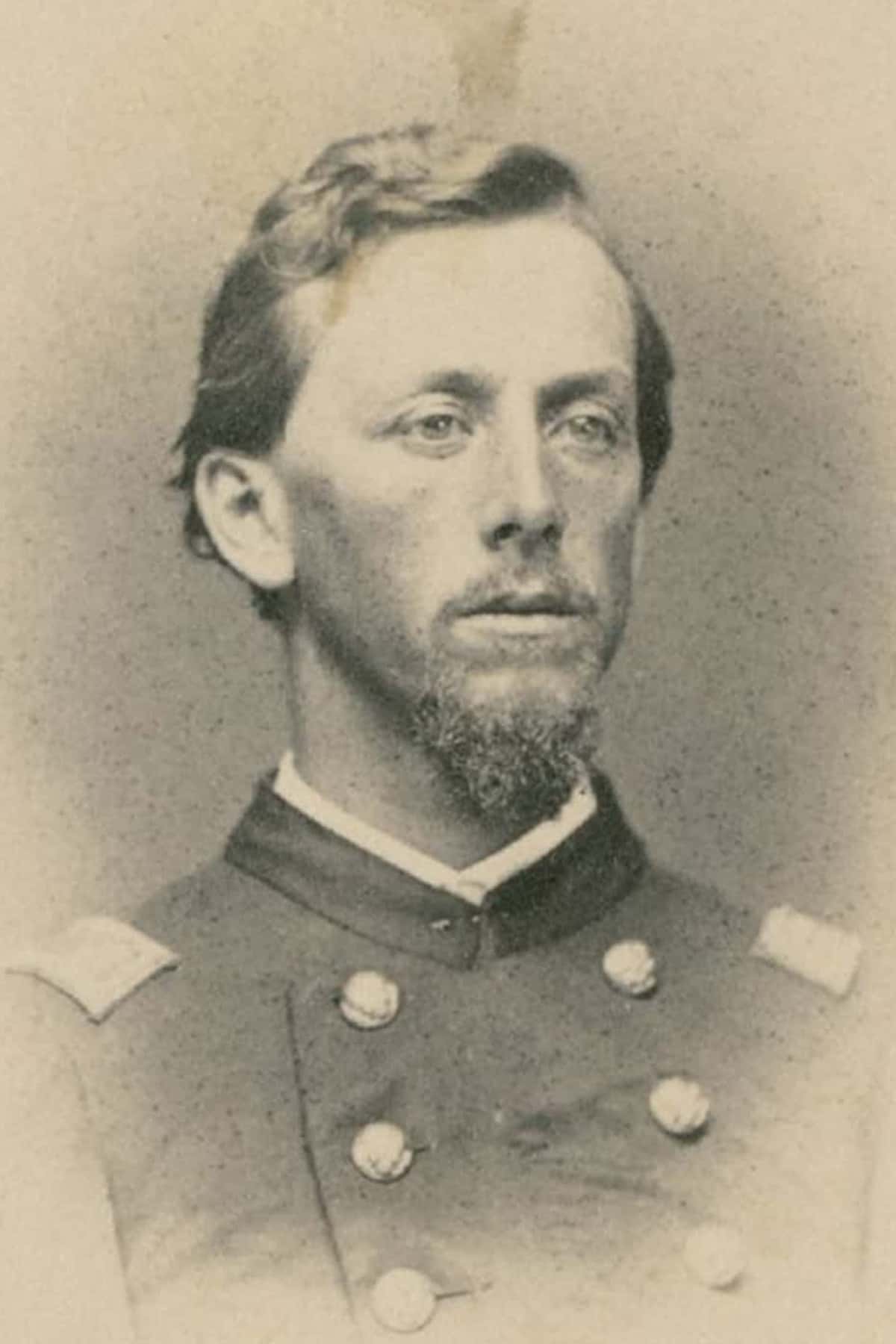

Winkler’s life as a Milwaukee lawyer starts with his birth in Bremen, Germany in 1838. [2] In 1842, his father Carl moved to a Milwaukee and served as a pioneer druggist on what is now Wisconsin Avenue. Carl’s family joined him in 1844. Winkler attended Milwaukee schools, then studied the law before being admitted to the bar at Madison in 1859.

He returned to Milwaukee and began practicing law until 1862 when he mustered in Milwaukee with the famous 26th regiment Wisconsin Infantry—a German regiment. [3] Winkler became the captain of the regiment’s Company B. On Oct 6th the regiment left the state via rail, headed for the Rappahannock River valley in northern Virginia where the regiment spent the winter in drill, guard and picket duty.

The first of Winkler’s letters includes the railroad scene upon the regiment’s leave-taking:

All along the road down to the depot people crowded upon us, rushed upon us, pulling the boys out of the ranks, shaking hands and kissing them and bidding them a final farewell. The scene at the depot was one of the most affecting I have ever witnessed. A tearful crowd waved a last farewell and tearfully our soldiers answered it. The most happy and light hearted wept there, but it was only for the moment of parting, once gone all were in good spirits and a more cheerful, happy and sprightly party has never been known than the 26th Wisconsin on the way to Washington. I had a revolver presented to me by some friends of the Milwaukee Bar just before leaving.

The Forrest Gump of the Civil War

During the 33 months that Winkler was deployed he fought in many of the most significant campaigns and battles of the forty-nine months of conflict. At different times and for different reasons the 26th was “attached” to the 2nd Brigade, the 3rd Division, the 11th Army Corps, the Army of the Potomac, the Army of the Cumberland, the 3rd Brigade, and the 20th Army Corps. The regiment participated in such significant and tremendously brutal events as the Battle of Fredericksburg (1862), “Mud March”, Chancellorsville Campaign, Battle at Chancellorsville, Gettysburg Campaign, Battle of Gettysburg, Battle of Wauhatchie, Chattanooga – Ringgold Campaign, Mission Ridge (1863); the Atlanta (Ga.) Campaign, Siege of Atlanta, Occupation of Atlanta, March to the Sea, Siege of Savannah (1864); the Campaign of the Carolinas, Battle of Bentonville, Advance on Raleigh, Occupation of Raleigh (1865) and the March to Washington, D.C. (June 17, 1865). Winkler began his tour as a Captain in 1862, named Major in 1863, and Lieutenant Colonel in 1863 when the predecessor of his command was discharged by reason of his wounds. In August 1864 he was promoted to Colonel and in July 1865 was brevetted by the War Department as a Brigadier-General, after the regiment mustered out. The regiment’s original strength included 1,002 to which recruits were added in 1864 to total 1,089. Of these totals, 284 died, 31 deserted, 125 transferred, 232 were discharged and 449 mustered out.

Captain Winkler’s first major duty was serving as judge advocate over many courts-martial. He would be commissioned at various times back and forth between judge advocate work to field service. In five or six cases he had to certify death sentences to headquarters. But so much for the certifications because all but two of his death sentences were commuted.

Besides ordinary judge advocate work, he had a famous and remarkable case during the war for which he was appointed defense counsel at the request of his client, Major General Carl Schurz. [4] In the Court of Inquiry was an investigation of Schurz and a part of his command that had not followed orders- as included in an official report by General Hooker about the night battle at Wauhatchie in Look Out valley Chattanooga. With Winkler as counsel the investigation was ended and the significant charges dismissed. [5]

Gettysburg Hero

The letters in the days before the Battle of Gettysburg have a disarming tone of casualness and calmness to the modern reader. They reflect a regiment officer who is unaware and without premonition of the tremendous bloodbath that awaited him for the three-day battle that began July 1.

On June 30, 1863 the regiment changed camp to a “sisterhood”—a convent on a wealthy campus belonging to the Sisters of Charity which included a boarding school (“it is vacation and at present most of the scholars away”) and a large frame house of the Sisters which they offered to the regiment as “headquarters.” The on-grounds priest “tells me that it was once used for an Orphan Asylum, and is …. kept as a refuge for the homeless.” [6] The day began with countermanding both reveille and orders to march such that “we were allowed to sleep a couple of hours longer.” The day ended after “the Sisters gave us a very good dinner which we all enjoyed heartily.” The next letter-entry is dated July 4th, 1863, uncharacteristically short and far less chatty than earlier entries. It stated simply: “In three days’ hard fighting we have whipped the rebels terribly; they’ve fled. We now start pursuit. I am saved from all harm, and that is all I can tell you now.”

Winkler returned to the convent and on July 6th began writing long missives to his wife, stating that “ I intended, at first, to give you a full account of the battle of Gettysburg as I saw it, but I have not paper enough to do it upon. I hate now to return to the dreadful scenes of strife.” His tone is notably changed; his long, detailed account is one of trauma and bewilderment. He discusses that the 26th Wisconsin Volunteer Infantry Regiment arrived on the Gettysburg battlefield with an effective strength of 516 in the early afternoon of July 1st. The brigade was heavily attacked from the front and was holding its own when a division to its east collapsed. Many horses, including his own were seriously wounded; Major General Schurz nearly suffered a shell casualty. By July 3 the brigade was forced back to Gettysburg but not before fielding serious losses including 46 were killed, 134 wounded, and 37 missing. Notably, four line officers were killed. The wounding or loss of commanding officers is significant. Winkler held the fourth highest rank in the regiment when, during the heat of battle, he was thrust by injuries of higher ranking officers into the role of acting field officer. At the end of the battle he led, seemingly stunned, he reports that “the 26th has only about 230 men fit for duty just now. A number, I believe, had been taken prisoner.” [7]

Back in Wisconsin: the Zelig of post-war Milwaukee Civic Life

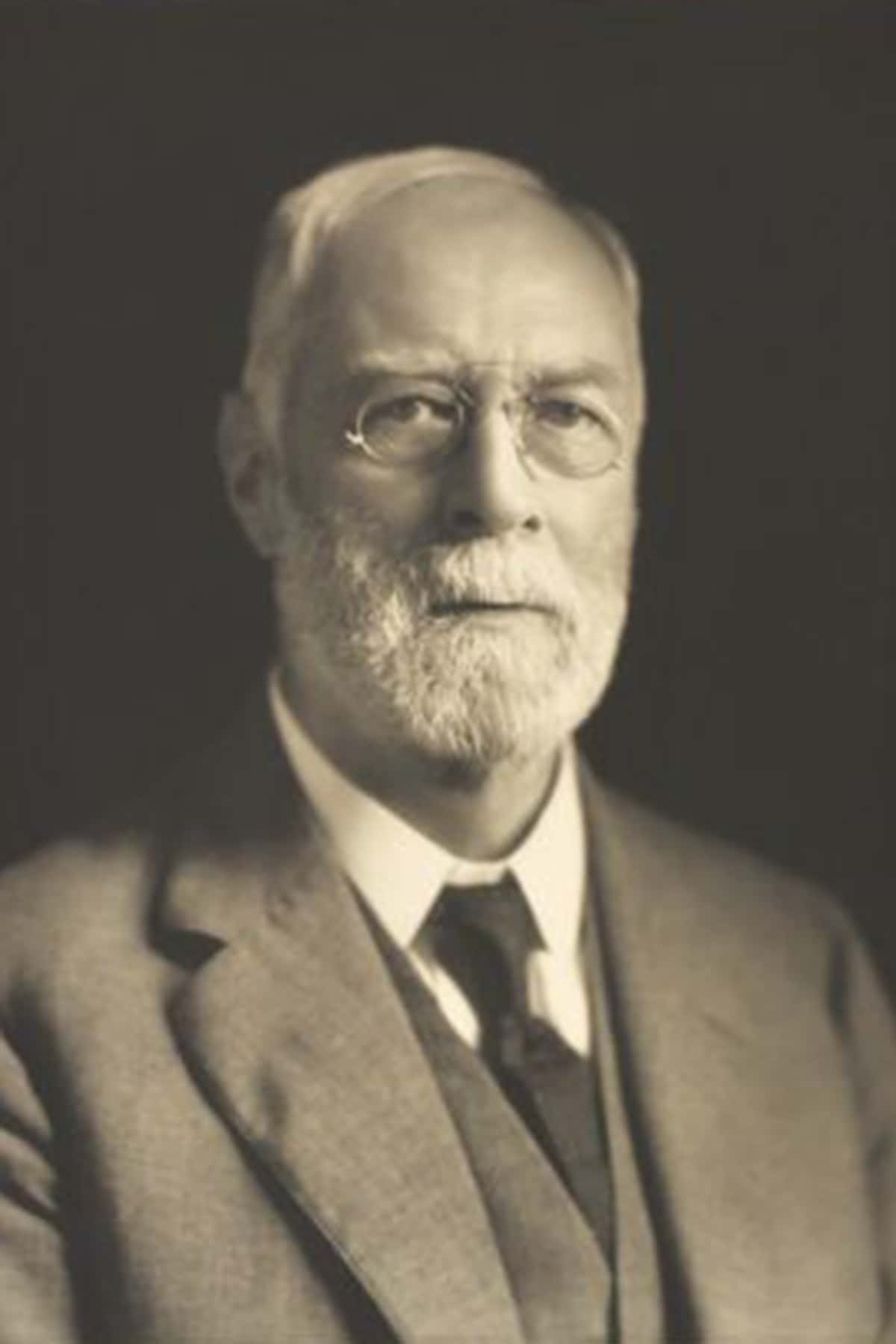

Law practice and business. General Winkler’s return to Milwaukee meant return to private practice. But he never was outside of civic life or out of “the limelight.” [8] As a practitioner he was associated at various times with the prominent attorneys of his time. At one time when his firm was known as Winkler, Flanders, Smith, Bottum and Vilas, it was nicknamed the “Honest Five.” [9] Winkler retired in 1913 from active practice. In 1898 he was named a trustee at Northwestern Mutual Life Insurance Company and served 32 years in that capacity, including serving as a member of its Finance Committee from 1898 to 1918 and its Executive Committees from 1899 until his death in 1921.

Political activities. The General continued his political activities that began shortly after the war when he served as an 1869 member of the Republican state central committee, an 1880 delegate to the Republican National Convention that nominated Garfield and an 1894 delegate who nominated Blaine. He was always a Republican but did oppose WWI and therefore publicly supported Wilson’s re-election. He presided at the Auditorium meeting when Woodrow Wilson came to Milwaukee in 1916 stirring the audience to anti-war sentiment. This child of Germany, who identified strongly with Germany, courageously insisted that the rulers of Germany cease violations of rights, continuing such public speechifying including in a 1918 speech recorded at the Milwaukee Bar where he said:

“As Abraham Lincoln’s era brought about the death of slavery, so will the present crisis, as we hope and believe, bring the death blow to international rapacity and list of conquest. We are confronted with a new crisis. It does not involve the enslavement of man but domination of force of arms of nation over nation, founded on the claim that might makes right.” [10]

In 1872 he served as a member of the state assembly and also a candidate for Congress which he lost; his 1892 candidacy for congress he also lost.

Bar and Reform Work. Winkler served as president of the State Bar of Wisconsin and as a vice president of the American Bar Association, and was instrumental in procuring and hosting the ABA’s 1912 conference in Milwaukee. [11] Winkler retirement in 1913 from active practice occurred at about the same time as the rising of Emil Seidel and Daniel Hogan- socialist mayors with whom Winkler was simpatico. As a member of the Milwaukee City Club and the Milwaukee Bar Association, he was involved in the 1916 creation of the Legal Aid Society.

Winkler’s reform efforts were both in leadership roles and in legislation drafting. He was a member and president of the Wisconsin Civil Service Reform League as president, and later an officer in the National Civil Services Reform League, for which his former client and commanding officer, Carl Schurz, served as founder and director.

In 1885 state legislation he drafted created the City of Milwaukee Fire and Police Commission—the first commission of its kind in the nation designed to curb the corruption and political influences of policing that had developed since 1855 (police) and 1875 (fire). In 1909 he was a member of the Milwaukee charter convention and drafted the home rule bill and the nonpartisan election law for Milwaukee.

Civic Leadership. Winkler was an active member and officer of the Phantom, Milwaukee and Old Settlers’ Clubs, the GAR, the Military Order of the Loyal Legion and a Member of the 26th regiment organization. In 1891 General Winkler, George Koeppen and Henry Gugler brought together about 60 other men at the Plankinton House Hotel and organized the Deutscher Club—to promote and provide a venue for German-American discussions and understanding during yet another period of immigration. Winkler drafted the bylaws and was elected first vice president. They met at the Old Opera House (near the Pabst Theater currently) until 1894 fire damaged the clubrooms.

Considering reestablishment or disbanding, Winkler led the club up Grand Avenue to the vacant Mitchell Mansion (Alexander Mitchell died in 1887) and offered $100,000 for the place which eventually evolved into the Wisconsin Club. They had an opening night party on May 1, 1895, with 450 attendees. [12]

In the accounts of Winkler’s funeral, all of these groups selected delegates to walk in the long funeral procession to Forest Home Cemetery, including actual pall bearers and a long list of honorary pallbearers.

Post-Script. Winkler’s letters reflect his being informed on the battlefields about current events and also reflect his opinions of those current events. For example, on Christmas Day 1862, he comments favorably about President Lincoln’s plans for issuing the Emancipation Proclamation, about which he read in The Atlantic Monthly. Having led troops and fought in the Battle of Gettysburg, the major dedication of the battleground as a cemetery would seem to be an event about which he would have commented. On November 18, 1863, he wrote Fannie a short letter about the weather and the inability of the regiment to carry out duties due to fog. On November 20, 1863 he discusses food—that biscuits replaced hardtack and that even though the biscuits were tough and were without butter and the coffee was poured without milk the food “constitute an excellent breakfast.” He continues his letter about the “luxury” of having potatoes the previous night before reporting on the praises his regiment received for a recent battle. He completely skips a letter on November 19, 1863, and any commentary of events of that day – when Lincoln delivered his game-changing Gettysburg Address.

Lee Matz, Wisconsin Historical Society, and Wisconsin Veterans Museum

[1] Frederick Charles Winkler: Milwaukee’s Hero of Gettysburg. Hitz, Louise Winkler, ed., Letters of Frederick C. Winkler: 1862 to 1865, (University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI, 1963); Watrous, Lieut.Col. Jerome A., ed., Memoirs of Milwaukee County, Vol. II (Western Historical Association, Madison, WI, 1909); Winkler’s Body on Way to City, Milwaukee Journal (March 23,1921); One of State’s Great Men, an American of Americans, Milwaukee Journal (March 23, 1921); Gen. Winkler Dead, Milwaukee Sentinel (March 24, 1921); Gen. Winkler, American, Milwaukee Journal (March 25, 1921); Court of Inquiry: On Maj.Genl. Hooker’s Report of the Night of Engagement of Wauchatchie, Argument of Maj-Gen. Carl Schurz, Delivered February 12th, 1864; (Viewed January 15, 2013); Quiner, Edwin Bentley, The Military History Of Wisconsin: A Record Of The Civil And Military Patriotism Of The State, In The War For The Union (Clarke & Co., Chicago, IL, 1866); Pula, James S., The Sigel Regiment: A History Of The 26th Wisconsin Volunteer Infantry, 1862-1865 (Savas Publishing Co., 1998); Byron Kilbourn Hall is Dedicated, Milwaukee Free Press (February 1, 1911); Peter Engelmann Hall is Dedicated, Milwaukee Free Press (February 9, 1912); Men of Milwaukee: Gen. F.C. Winkler, Evening Wisconsin (August 1916); City Will Offer Tribute Sept. 14 at Juneau Grave, Milwaukee Sentinel (September 1, 1918); Lincoln’s Tragic Death, West Bend News (April 21, 1915); Milwaukee Pays Tribute to Juneau’s Memory AS Founding is Celebrated, Milwaukee Sentinel (September 14, 1918); Union of Two Clubs: Germania and Deutscher Become One, Milwaukee Sentinel (February 14, 1897); Old Settlers’ Club Honors Gen. Winkler, Milwaukee Journal (March 15, 1918).

[2] Eighteen thirty-eight marks ten years before the German Revolution—the premise and motivations of which play important roles in both Milwaukee’s and Winkler’s “identity” and history.

[3] President Lincoln authorized General Sigel to raise twelve infantry regiments from among German populations. He asked Wisconsin’s Governor Saloman to raise one of the regiments; he, in turn, entrusted the formation to Milwaukee lawyer William Jacobs. A full regiment was raised and mustered from around the state on Sept. 17, 1862. The 26th Regiment took Basic Training at Milwaukee’s Camp Sigel, located within the contemporary street-boundaries of Irving Pl., Kane, Oakland, and Farwell. William Jacobs served as the regiment’s Colonel. Its 11 companies consisted almost exclusively of men of German birth or German parentage.

[4] Schurz was a resident of Watertown, Wisconsin, having been exiled from Germany during the failed revolution in Germany. As native Germans, Winkler only was acquainted with him in Wisconsin prior to the war. It was not until later during the war that Col. Winkler was attached to Schurz’s military staff and then appointed counsel under Schurz’s command. Besides a battlefield commander and strategist, Schurz was a confidante of Lincoln, U.S. Ambassador to Spain, a U.S. Senator from Missouri, Secretary of the Interior in the Hayes administration, author of a biography of Henry Clay, president of the National Civil Service Reform League, and an editorial writer for Harper’s Weekly. He gave many speeches and lectures and wrote prolifically. While he promoted civil service reform, environmental preservation and arbitration for the settlement of international disputes, he opposed slavery, inflationary monetary strategies, and U.S. imperialism. His wife, along with Schurz, introduced and promoted kindergarten as an education reform measure.

[5] The issue under investigation was Schurz’s command’s failure to appear to fight until the morning, only after one of the few battles in the Civil War conducted at night ended.

[6] Winkler notes that indeed “when forty-two families of the village were made homeless by the fire of three weeks ago, this house offered them shelter.”

[7] The State of Wisconsin dedicated a monument to the 26th Wisconsin Infantry Regiment at Gettysburg on June 30, 1888.

[8] For examples, he served as a delegate from Wisconsin to the 50th anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg, the 1915 speaker in West Bend before 500 people for the 50th anniversary of Lincoln’s assassination, the 1918 speaker at the 100th anniversary of Solomon Juneau’ arrival to Milwaukee from Canada, and the 1911 and 1912 dedications, respectively, of Byron Kilburn Hall and the Peter Engelmann Hall in the auditorium.

[9] He declined an appointment to office of attorney general of the Eastern District of Wisconsin.

[10] It was in 1918 that Theodore Roosevelt returning to the city where he was nearly assassinated five years earlier, also honored Winkler during a speech saying that “I asked that there should be with me on the platform a man whole I have always considered a model for me and my sons to follow as an American citizen of the highest and best type, as representing the kind of Americanism I preach—General Winkler.”

[11] Winkler’s obituary lists him as a president of the Milwaukee Bar Association, however, the MBA does not include his name among its presidents.

[12] In that year, the Deutscher Club removed what was a conservatory on the first floor and built a bowling alley; the club also built the Grand Ballroom on the second floor. The bowling alley was removed in 1950 for the main first-floor dining room which is now the Wisconsin Club’s current casual restaurant, Alexander’s.