“Black Night Brawl was instrumental in mobilizing Milwaukee’s gay community to resist homophobia, form activist organizations, demand liberation, equality and change…” – From the City of Milwaukee’s Proclamation, declaring August 5, 2021 as “Black Nite Brawl Day” in honor of the first recorded LGBTQ uprising in Wisconsin history

On August 5, 1961, a young black transgender woman summoned the courage to fight back against homophobic violence that invaded one of her community’s only safe spaces, the Black Nite bar on 400 N. Plankinton Avenue.

She knew her very existence was criminal, her actions could have extreme social and legal consequences, and she may even be killed. But Josie Carter did not run from a fight. With violence on the doorstep, she beckoned to her community to stop running and start fighting back. The act inspired something they had never felt before, a sense of pride in themselves and each other.

As they defended their space and themselves against a violent invasion, they felt part of a community for the first time. The Black Nite Brawl, as it became known, triggered a timeline of substantial cultural change in Milwaukee.

“On the great game board of local LGBTQ history, all the dominoes lead back to the Black Nite,” said Don Schwamb, founder and webmaster of the Wisconsin LGBTQ History Project. “Nothing was ever quite the same again after that night.”

News coverage of the Black Nite continued for over a week, revealing to isolated LGBTQ people that they were not alone in the world. As people found their community, they began to demand liberation. Some of the earliest gay rights activists, including Eldon Murray and Alyn Hess, cited the Black Nite Brawl as an early glimmer of hope and a spark of revolution.

Enterprising business owners began to open more and more bars catering to LGBTQ people, including some of whom identified as LGBTQ themselves. By 1969, over three dozen gay bars had opened in Milwaukee. The Black Nite was not one of them.

The bar was forced to close, and the block was deliberately demolished to disperse the gay neighborhood that had been thriving since 1949. The first generation inspired by those historic events was almost entirely lost to AIDS. Eventually, the Black Nite was remembered only by a shrinking group of aging survivors. If not for the combined efforts of Dr. Brice Smith and the Wisconsin LGBTQ History Project, those events could have been forgotten entirely.

“Thanks to the efforts of the Wisconsin LGBTQ History Project, this seminal event in our community’s history has been reclaimed from storytelling lore,” said Dr. Smith. “For more than 50 years, Josie Carter was encouraged time and again to recount the night she fought off homophobic instigators and led her queer bar-mates in defending one of the few city spaces where they were free to be.”

Dr. Smith is the author of Lou Sullivan: Daring To Be A Man Among Men. He also served as coordinator of the Milwaukee Transgender Oral History Project, where Josie’s account of the Black Nite Brawl was first recorded in 2011.

Unlike the Stonewall and Compton’s Cafeteria riots, the Black Nite Brawl did not pit Queer and Trans people of color against the police. When the paddy wagon showed up, Milwaukee police stood with their friend Josie on the right side of history, rounding up the queer community’s attackers.

“Josie Carter was a legend while she lived, leaving her mark on all of us blessed to know her. Like Josie, the Black Nite is gone. But the brawl that occurred there on August 5, 1961 and the classy lady who started it continue to inspire us to this day,” added Dr. Smith.

Josie passed away in 2014, never accepting or receiving any formal recognition for her pivotal role in changing Wisconsin LGBTQ history. She was survived by one son, and countless other “children” she had informally adopted, coached, and mentored over the years – after their own families had rejected them due to their gender or sexual identities.

Milwaukee has never been like New York and San Francisco, but the Midwest still had its heroes like Josie Carter, Eldon Murray, and Lou Sullivan who showed that making friends was as important as battling enemies. They did not just demand rights, but rather attained them through hard work and good sense.

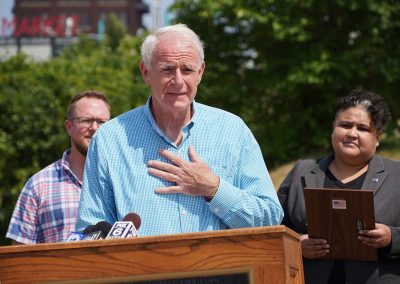

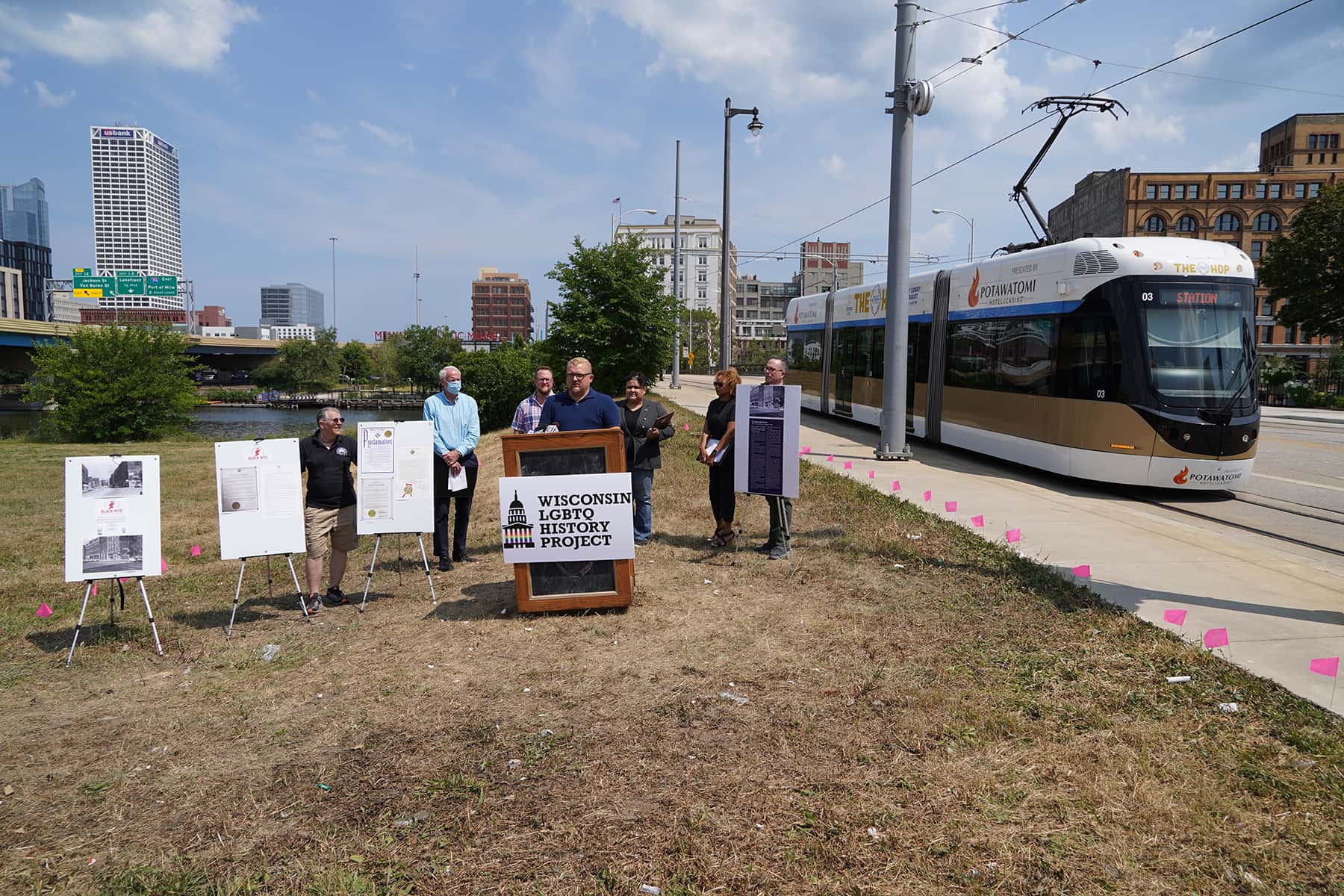

The Wisconsin LGBTQ History Project hosted a short media event on August 5, at the scene of the Black Nite bar. Featured speakers included Elle Halo, transgender rights activist, Mayor Tom Barrett, Alderwoman JoCasta Zamarripa, Dr. Smith, and Wisconsin LGBTQ historians and activists Michail Takach and Don Schwamb of the Wisconsin LGBTQ History Project.

The Wisconsin LGBTQ History Project began as a collaboration between PrideFest Milwaukee and the National Gay and Lesbian Archives to preserve and protect local LGBTQ history. Since 1995, the Project has grown from a humble table exhibit to the state’s largest collection of LGBTQ memories and memorabilia.