“The Arts Page” profiled a local photographer who rediscovered an abandoned art for taking photos. The award winning Milwaukee PBS show hosted by Sandy Maxx did an interview with Margaret Muza, who has gained national attention for using film using techniques from the mid-1800s. Sandy Maxx shared her insight and reflections from the experience of producing that episode.

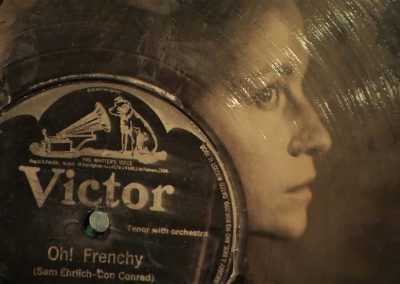

A stark image can warm hearts. And bring people together. Capturing a moment in time. The tintype photography process is a big contrast to how we use digital photography in our daily lives.

All the adjustments and proper placements to set up and, then, it goes by, literally, in a flash. Then you wait patiently as the chemical bath slowly reveals the image. Milwaukee artist Margaret Muza’s pursuit of these moments and her enjoyment of the experimentation with the historic and precise process is fascinating to observe.

I had the pleasure of spending an afternoon with “The Arts Page” TV crew in Muza’s studio to learn more. As the Pfister Artist in Residence at the time, her creative approach was observed in a fish bowl type setting that invited questions from curious guests.

For our TV feature, I got to be a model for a tintype photo. I enjoyed my experience inside the studio observing the process and getting to know Muza. But the most enriching moment came in an experience just outside her studio.

Every Pfister Artist in Residence creates a legacy piece to be displayed at the hotel after they move on. I happened to be sitting on the couch next to the spot across from the Artist In Residence studio, when Muza’s legacy piece had just been hung on the wall that morning. It was an image of Anthony and Dennis, two of the hotel’s stewards who were responsible for some of the most physical and unglamorous work in the hotel, standing outside one of the Pfister’s service entrances.

It was a magical moment when one of the subjects of Muza’s portrait walked by as he was working and saw it for the first time. Looking up from my laptop to see who was standing near me, I saw this tall man gazing at the portrait with a smile and I realized who he was.

“That’s you!” I said to him.

“Yes, ma’am,” Anthony said.

“You’re now an official part of this hotel and a true part of its history. How does it feel?” I asked.

He shyly said, “It’s nice. Really nice.”

He walked through a door across the hall and I resumed my computer work for another half hour or so. During that time time, other Pfister employees came by to look at the portrait. Some in pairs, others with Anthony, who joked that it had been very cold the day that photo had been taken. Others stopped by solo, who murmured “cool” and “wow.”

The moment in time that Margaret Muza captured, it not only documented an important part of the Pfister Hotel’s family but also brought that community a little closer together.

Enjoy “The Arts Page” feature on Margaret Muza and learning how she creates these magical moments.

The art of photography has made stunning technological advances over the last 150 years. Today, everyone who has a smartphone carries an advanced camera, which has given rise to the selfie phenomenon.

I use a lot of old cameras, old lenses. The one I use the most is an 8×10 camera from 1903 with an old portrait lens. These machines are really simple. Really, it’s kind of just a box with a lens on it, so it’s not a complicated machine at all. That’s what’s amazing about them.

Even though they’re so old, you know, I’m using them over 100 years later. And I love that about them, because most of our modern technology doesn’t work after two or three years. The first time I saw a tintype appearing in the fixer, I felt like I had seen a ghost. I got goose bumps, and I was just — my eyes watered because it was so spooky and so beautiful.

And I thought, how did that happen? How can this image be before my eyes? Which is something we don’t think about when we’re looking at images on a screen. So there’s complete magic there, and I still feel that way every time I take a picture. I’m always surprised by what I see. It always turns out differently than imagined.

The wet-plate process is an old photographic method that uses wet chemistry to make an image, instead of, say, film or negatives. I use aluminum plates and glass plates. So, then I use a collodion, which is a liquid emulsion that I pour onto that plate which becomes light-sensitive through a series of chemical steps. It sits in a bath of silver nitrate, where it becomes light-sensitive in the darkroom.

And then I use developer that I make myself, and an old varnish recipe that’s a Civil War era recipe. This process really attracted me because it’s a little bit unpolished. So, the image is kind of messy. There’s lots of artifacts that show up, little smears, fingerprints. And I like the look of that.

I really like photographing people. Someone by themselves is really, like, my ideal subject. I really like to be able to focus on every aspect of someone’s face, lighting them perfectly, and then developing them perfectly.

This process is fulfilling because it still really challenges me, I think, because I have so much to learn yet, I’m still really hooked, and it hasn’t let me go, you know, because I really am challenged by it constantly. And I want to master it.

– Margaret Muza

Sandy Maxx

Sandy Maxx, The Arts Page

Milwaukee PBS

Originally broadcast as History Intersecting Art – Season 6 Episode 5