On a mild winter morning just after the polar vortex, my twin sister Lena and I got the opportunity to have a tintype photoshoot with Margaret Muza. We have posed together for selfies and had friends take pictures of us. But we have not sat together with a professional photographer for a studio portrait since we were little, and this experience was something completely new.

The wet plate studio for Margaret, a Milwaukee-based photographer, is nestled within a cluster of industrial buildings near Jones Island. Her space is decorated with vintage but functional furniture, period clothing, and antique memorabilia that makes visitors feel like they stepped back in time.

It was a thrill to learn about how a method for making images from the Civil War era battlefields found its way to a small studio in 21st century Milwaukee, and that my twin and I were able to participate in the process.

Margaret’s art form is considered a rare specialty from mainstream photography, with only two other people in Wisconsin actively producing tintypes. When she is not in her studio, she travels to locations around the state using her car as a makeshift darkroom, capturing moments fixed in time.

Tintype is a photograph made by creating a direct positive image on a thin sheet of metal that is later coated with a dark lacquer, and used to preserve the photographic emulsion. Tintype photographs were widely used in the 1860s and 1870s but became less necessary in the early 20th century with the evolution of camera technology. Tintype was produced in a variety of settings from carnivals, county fairs, and along city sidewalks. The format became increasingly successful in its early days, because it was inexpensive and quick to make, a necessity especially during the American Civil War.

When we arrived at her studio, Margaret was enthusiastic and sweet, and her warmth made Lena and I feel comfortable instantly. She posed us right away, gave us insightful information about the process, then snapped the photo. Shocked, Lena and I smiled at each other and wondered if there was more to be done – it seemed too easy – but that was it.

The unique thing about tintype photography is that it captures the moment only once, with all the imperfections, and cannot be reproduced because there is no negative. With modern film or even digital photography today, multiple shots can be taken, there is no limit to how many prints can be made, and there are more opportunities to correct for flaws. The experience of posing for the tintype felt much like trying to catch a single snowflake falling in the air and then preserve it within warm hands. The moment was that fragile, and also equally special.

As I sat in front of the century old camera, I was hyper-aware of my how my body was positioned, the way my hair rested along my face, where my clothing felt loose or tight, and facial expression. After Margaret[m][n][o][p] exposed the chemical covered plate of metal to light, and then removed it from the camera, I was so anxious to see the image that was captured.

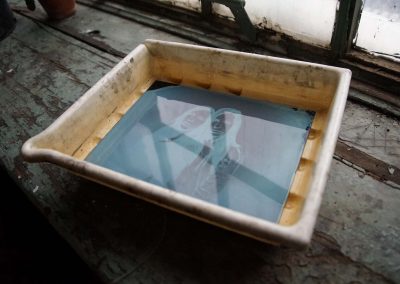

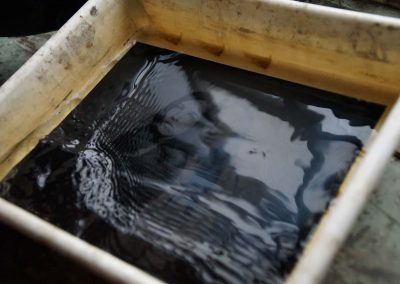

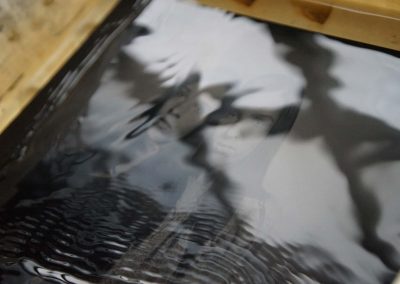

Lena and I waited for Margaret to come back from her darkroom with the plate prepared and ready to develop. The three of us huddled in a corner near her window and watched as the liquid was poured and the chemical reaction cause the image appeared on the aluminum little by little. It was very much like watching a Polaroid develop.

We stood in awe as it appeared, showing our hands intertwined and our bodies leaning toward one another. My anxiety drifted away as I realized that this special moment was captured perfectly, even with its imperfections, and I felt very grateful to have shared it with my sister.