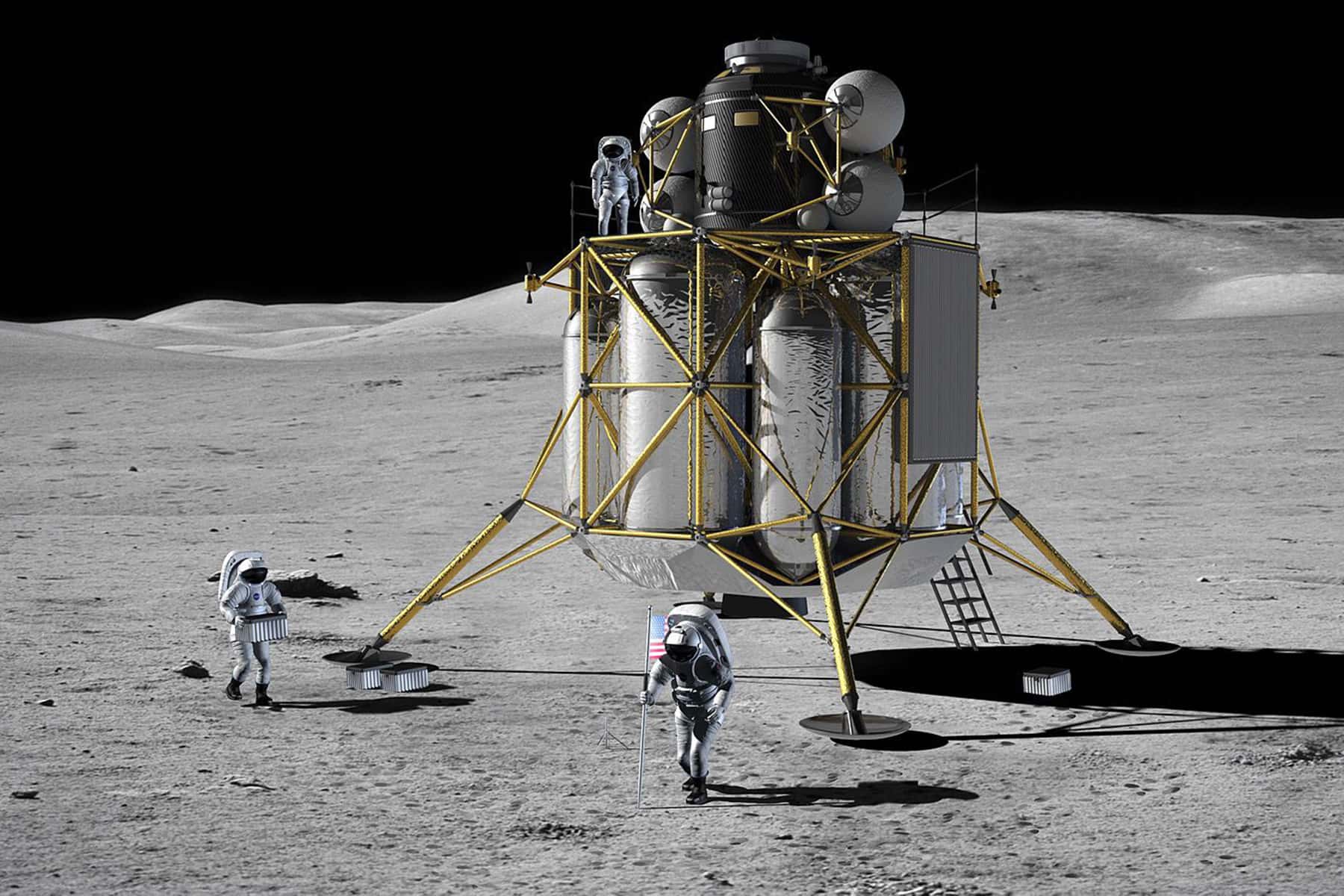

Carthage College professor Kevin Crosby and his team of students in Kenosha are hoping the data they gather from sending an experiment into space will help them solve one of aerospace engineer’s greatest problems: how to measure fuel in zero gravity.

A rocket launched Crosby’s scientific package in January. Three plastic tanks containing different amounts of water were outside of earth’s atmosphere for about four minutes. Space crafts have to tow extra fuel, and that can cost millions of dollars.

“So there was this famous moment on the moon landing,” Crosby said of the July 1969 Apollo 11 moon landing. “When the alarms were going off and they had 30 seconds before they were going to run out of fuel — turns out they weren’t going to run out fuel, but it was a very tense and traumatic moment because we don’t have a good way of knowing how much fuel is in the tank.”

In 2010, Crosby and his students applied to design and develop an experiment to test an idea by Kennedy Space Center engineer Rudy Werlink. Werlink hypothesized a spacecraft’s natural vibrations could be used to determine the amount of fuel left in the gas tank.

Dozens of schools applied to test Werlink’s theory. Werlink chose the small liberal arts college in Kenosha, and he continues to work with the school because he believes Crosby and the Carthage team are close to solving the problem.

“Crosby really gets his students to do things that are beyond their normal duties,” Werlink said. “We have this great data set. Even from the first flight.”

Since 2011, Crosby has worked with a new group of students, usually about 10 to 20, on the Modal Propellant Gauging (MPG) project. Using the same idea of running a finger along the rim of a wine glass to hear different sound pitches, Crosby’s team has filled plastic tanks with different amounts of water to hear how the liquid redistributes itself in space.

“Instead of using our ears, we use a lot of mathematics to detect that difference in pitch and translate that difference in pitch to determine how much gas is in the tank,” Crosby said.

It seems to be working. The work by Crosby and his students has been refined several times. The early flights were short. Maybe 20 seconds. This group of students flew two parabolic flight campaigns for the MPG project in March 2018 and November 2018. These flights took place in Florida — leaving from the Sanford International Airport and flying out to the designated airspace over the Gulf of Mexico.

In Texas, the experiment went up on the New Shepard Rocket, part of Blue Origin, the space company owned by Amazon’s chief Jeff Bezos.

“The idea is you develop an experiment, you test it, you reuse it and these can be done on an annual basis, as opposed to traditional space, where billions of dollars, do or die,” Crosby said.

Before commercial space access was a reality, the only opportunity to test hardware and new concepts was on the International Space Station. The development time for space station experiments is several years with costs typically in the millions of dollars, Crosby said.

While many universities have partnerships with NASA, Kenosha’s Carthage College has one of the longest continuously operating space science programs in the country. It has existed since 2011. It’s also the home of the Wisconsin Space Grant Consortium, which connects NASA with dozens of Wisconsin colleges and organizations.

Celestine Ananda is a physics major with minors in math and computer science. The 21-year-old hopes to one day work at a private space company as an aerospace engineer. She said her classes at Carthage are extremely difficult but being in the lab motivates her.

“Being able to see directly what we are working toward, understanding and having the hands-on application of what we are learning, really drives back the passion towards the classroom,” Ananda said.

Ananda said she wouldn’t have attended Carthage if the space consortium weren’t housed there. And now, the New London native says her expectations have been exceeded.

“I never would have thought that we would be able to build something that would go to space,” she said. “Or that we would have NASA internships or that we would get to do these parabolic flights or build a satellite. It’s amazing.”

Crosby said the MPG project is in the transition phase from proof-of-concept to being able to establish if it’s viable to be used in space. He recently spent 15 months on sabbatical at the Johnson Space Center in Houston and Kennedy Space Center in Cape Canaveral, Florida working with a team of engineers to bring this technology to fruition on an Orion mission.

“There will be one more Blue Origin New Shepard flight of the MPG technology at the end of this year, and a space station experiment is in development,” Crosby said.

The MPG technology was recently tested on a prototype planetary lander developed at the Johnson Space Center. Crosby and crew believe one day, their work will be in on an actual spacecraft.

Corrinne Hess

NASA

Originally published on Wisconsin Public Radio as Carthage College Teams Up With NASA To Solve 50-Year-Old Problem