Trigger Warning: this essay contains the mention of Rape and Sexual Abuse

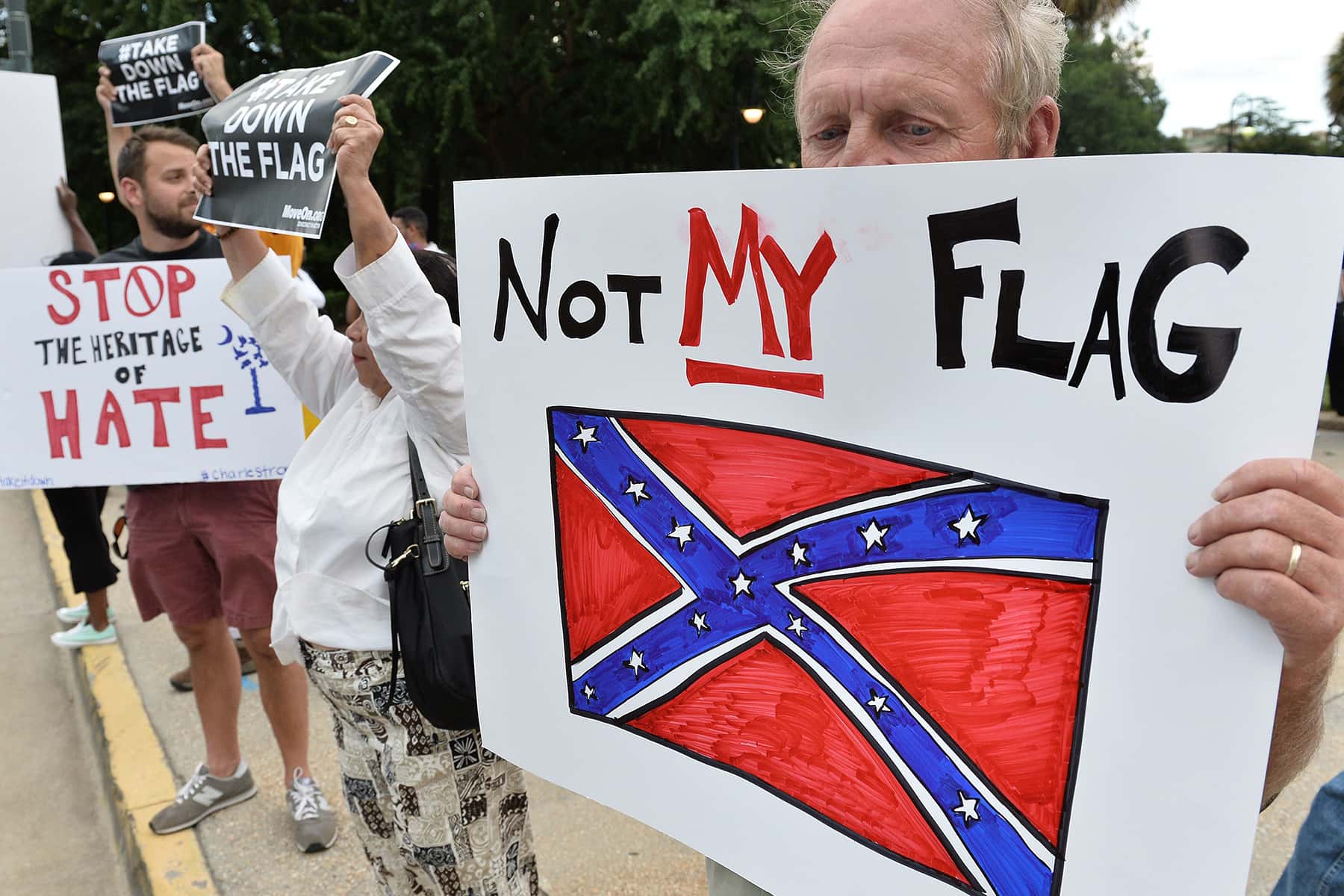

As a Black woman born in Louisiana, I was elated by NASCAR’s and the U.S. Navy and Marine’s decision to ban the Confederate flag because those are three fewer places where a flag that represents systematic torture is flown.

Supporters of the stars and bars love to argue that the flag stands for rebellion, and that flying the flag is not “about slavery,” but about the pride of being from the South. However, the flag makes me think of something else: violence—sexual violence, in particular. It reminds me of Sam, Louisa, Ann, Henrietta, and Florence, who refused to let their trauma die in silence.

Sam and Louisa Everett did not have a beautiful floral June wedding. Louisa, on her wedding day, did not wear a white dress with flowers decorating her hair. Sam did not wear a nice suit. There was no dancing, deep kisses, or smiling family members. Sam and Louisa were brought together by their owner “Big Jim” McClain to reproduce.

In 1936, the two were interviewed in Mulberry, Florida, by Pearl Randolph as part of the Negro Writers Unit. The goal was to collect as many firsthand accounts as possible from those who were formerly enslaved. Now permanently housed in the Library of Congress, Louisa’s recollection of her wedding night is something out of a horror story:

“Master Jim called me and Sam ter him and ordered Sam to pull off his shirt—that was all the McClain niggers wore—and he said to me: Nor[nickname of Louisa], ‘do you think you can stand this big nigger?’ He had that old bull whip flung acrost his shoulder and Lawd, that man could hit so hard! So I jes said ‘yassure, I guess so,’ and tried to hide my face so I couldn’t see Sam’s nakedness, but he made me look at him anyhow. Well, he told us what we must git busy and do in his presence, and we had to do it. After that we were considered man and wife.”

Jim McClain’s cruelness was not specific to the Everetts. He did this as a businessman and for his own sick pleasure. The Everetts also recalled that Jim McClain would often force those he’d enslaved to have sex in his presence to assure they bred healthy offspring. Other times, he would invite friends to watch them have forced intercourse, allowing his friends to rape young women as their husbands or lovers watched, unable to save them.

I remember sitting in silence after reading Louisa’s words about her “wedding night.” What must it have been like to be told that you would reproduce with a man, under penalty of violence, for the purpose of creating additional income for your owner? To know that child was not being created to be loved, but to expand the budget line of the plantation. By my calculations, Louisa, who was 90 at the time of the interview, would have been in her early to mid-20s when she and Sam were forced to have sex. Just a bit younger than I am now. I also thought about Sam. What must it have been like to be introduced to a woman and then told after one forced experience, where your master observed you, that this was to be your wife? How did Sam and Louisa navigate that trauma and build a life together?

When we talk about slavery, we tend to water down the experience to images of a slave being whipped a couple times or picking cotton for long hours. It is easier that way. Slavery was, in the mind of many White Americans, bad but manageable. Those who cling to mythical interpretations of the antebellum South actively search for exceptions such as kind masters who were misguided by the times they lived in. Our diluted, oversimplified view of slavery and reluctance to center slave narratives within history has led to the delusion that slavery was a bit bad, and not the traumatic experience filled with physical abuse, rape, and torture that it actually was.

We know this from the stories left to us by those who were enslaved.

Harriet Jacobs wrote extensively about avoiding her master’s advances in her book, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. Her master’s harassment eventually motivated her to go into hiding for seven years in her grandmother’s house. Jacobs was extremely open about her master’s harassment. However, not everyone used the same candidness as Jacobs and the Everetts. Understandably, when many talked about the sexual violence, they were cautious.

According to a 2016 Slate article, the survivors of chattel slavery were being interviewed in the middle of the Jim Crow era, when many of their masters’ descendants would have been living. While retelling their trauma, they also had to worry about White Southerners who did not wish to see their antebellum fantasy tarnished. Other times, the painful memories were too much to recall. As Ann Odom Boyd of Alabama told her interviewer, “Slavery was a sad life. Can’t tell it like it was.” Many clues about the lack of sexual freedom in slavery can be found in former slaves’ testimonies about the rigidness of marriage.

Florence Bailey was interviewed in 1935 as part of a project run by Professor John B. Cade, at Southern University, Bailey was a “house slave” in Mississippi. Remembering her time of bondage, she commented that, “There was no marriage during slavery. The master would just tell a certain man or woman to go and live together, it didn’t matter whether they were in love or not the first time they met each other.” Those in slavery did not have the luxury of personal lives or boundaries. Every part of slaves’ existence was controlled by their master, especially their genitals, which were viewed as an economic asset. This is shown in a narrative by Henrietta Butler in 1940, when interviewed by the Louisiana Works Progress Administration: “She [her mistress] made me have a baby by one of dem demmens on de plantation. I gets mad every time I think about it…”

In a 2018 article, Professor Stephanie Jones-Rogers argues that sexual coercion was a key element of slavery. Recalling one mistress who strategized her finances on Black women’s bodies, she stated, “She knew all too well that pairing enslaved male and female bodies together was the key to increasing her economic investments…” Marriage and sex for the enslaved was not about their happiness, it was a long-term investment for their masters.

The topic of sexual violence is often left out of the history of chattel slavery because it makes us uncomfortable. Its presence completely derails all rosy narratives we carry of the antebellum South and makes us reckon with a violent past. Scarlett O’Hara isn’t such a romantic Southern belle when we realize she knew Mammy was being forced bred like a cow. It is hard to claim your flag represents rebellion when it also stands for a nation-state where White men raped women as their husbands watched. It is difficult to put a stars and bars sticker on your truck when you think about the frightened girl who hid in an attic for seven years to avoid being raped.

Reflecting on these narratives, I think about all the Black women and men on those plantations, who were denied healthy sexual interactions by their owners. I think about the Black women who bore children under threats of violence, only to have those children torn away from their arms to be sold. As a born Southerner, the stars and bars is part of my history. And I find nothing beautiful about this history, nor do I see anything about it in which to claim pride. I find myself disgusted by the argument that it is a rebellious flag for the South.

The Confederate flag represents one thing: A White nostalgia for a time when Black people “knew their place.” It represents their longingness for the days of beautiful plantations, Southern belles, and negroes singing in the field. The stars and bars is a symbol in the racist mythology of many White Americans that the world was a bit easier when someone with a whip in their hand watched Black people. The idea that one can “pick the good parts” of Southern history to be prideful in is privileged. It means you can happily ignore the legacy of that flag because the history it represents never hurt you or your family. The flag is heavily embraced by many White people because it centers privilege, the White race, and power.

As a Southerner, I cannot abide by the usage of this flag as one of a beloved heritage.

I was born in Opelousas, Louisiana. Half of my family is White and the other half is Black. My White family has been in Louisiana since the 1700s. They would have seen the birth of the United States, the acquisition of the Louisiana Purchase, and the Civil War. On the other side, my Black ancestors came to this nation in chains. My Southern roots are long and deep.

As such, I do believe the flag should be displayed, but not at NASCAR, in the U.S. military, in college dorms, or at political rallies, but in a place where all representations of violent history belong: in a museum. And next to it, centered for the world to see, are the stories and images of the violence suffered by Black lives under the Confederate flag.

Mladen Antonov

Originally published by YES! Magazine as The Confederate Flag Represents Sexual Violence

Nikki Brueggeman is a writer based out of Southern California. A graduate of Washington State University, she writes about history, Blackness, and women.