By Aram Goudsouzian, Bizot Family Professor of History, University of Memphis

James Meredith was walking down Highway 51 just south of Hernando, Mississippi. It was June 6, 1966, the second day of his planned 220-mile trek from Memphis to Jackson, which he undertook to encourage Black people to overcome racist intimidation and to register to vote.

As cars filled with newspaper reporters and police officers rolled nearby, he walked a sloping stretch of road lined with pine trees. He heard a shout: “James Meredith! James Meredith!”

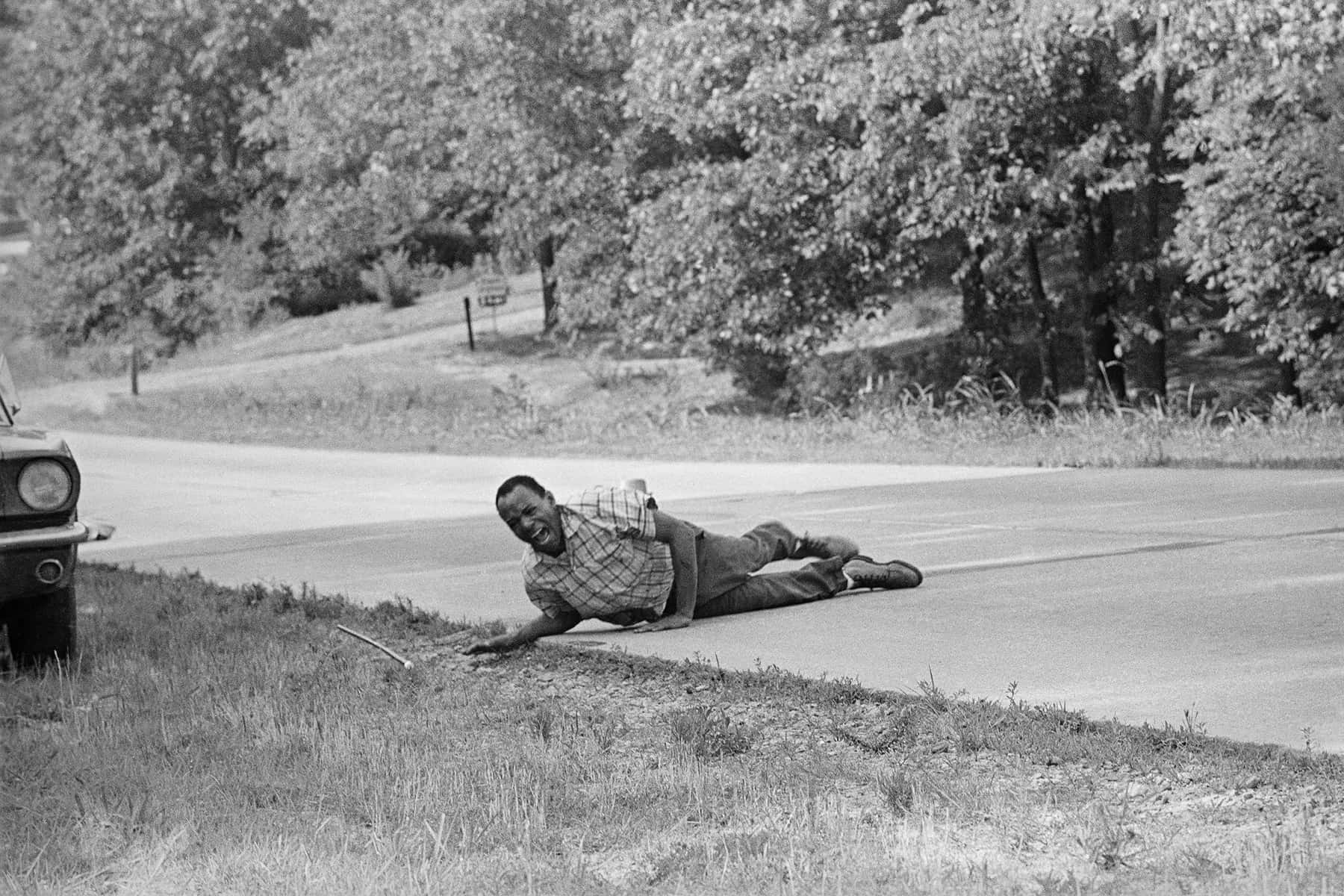

A white man in a roadside gully lifted his shotgun, aimed at Meredith and fired. Meredith was hit and crawled across the road, his eyes wide with panic. As he splayed onto the gravel shoulder of Highway 51, blood soaked through the back of his shirt.

The attack, which happened 55 years ago, propelled Meredith back into the spotlight. Four years earlier he had integrated the University of Mississippi, which prompted bloody rioting and a political crisis. Now, in 1966, photographs of an anguished, injured Meredith splashed across newspapers’ front pages, and the media again admired his stoic fight for racial justice.

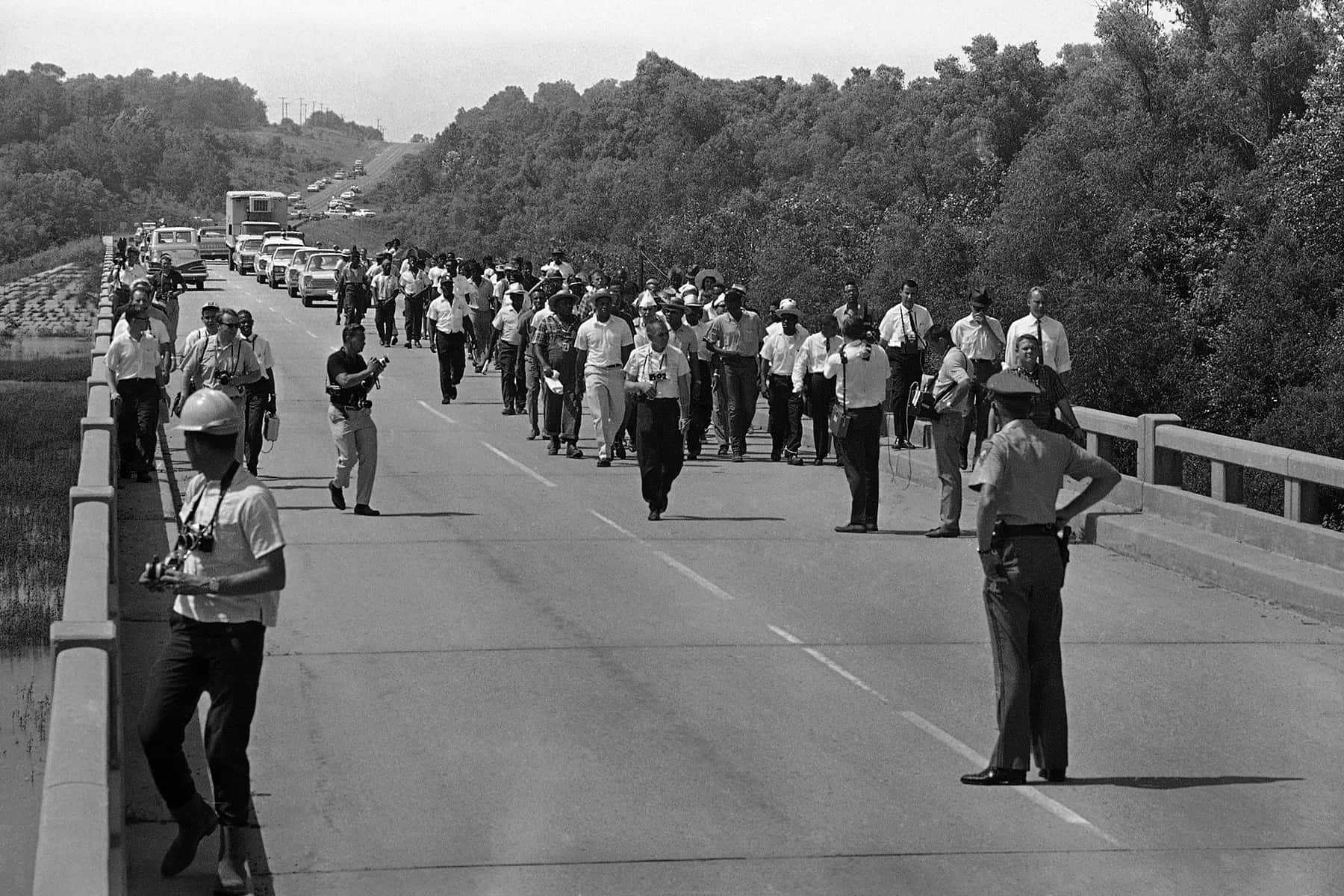

Civil rights leaders and thousands of others took up Meredith’s walk, transforming it into a huge demonstration known as the “Meredith March” and “March Against Fear.”

But Meredith, who survived his wounds, resisted his assigned political role. While liberals celebrated his sacrifice, he grumbled that he should have carried a gun, and in the ensuing weeks, he complained that the march lacked order, imposed upon Black Mississippians and endangered women and children.

The shooting revealed how James Meredith fits no conventional political category. He is a civil rights hero who does not associate himself with the civil rights movement. He espouses conservative ideas of self-reliance, discipline, morality and manhood, yet he proclaims a radical mission to destroy white supremacy.

Meredith’s historical meaning is slippery, but that very inability to pin him down can teach important lessons – not only for how to remember the 1960s, but for how to think about social change. As Meredith’s example reinforces, humans are too complicated to assign to one political tribe. Major movements, moreover, need contributions from people with a range of ideologies.

‘Paradoxical personality’

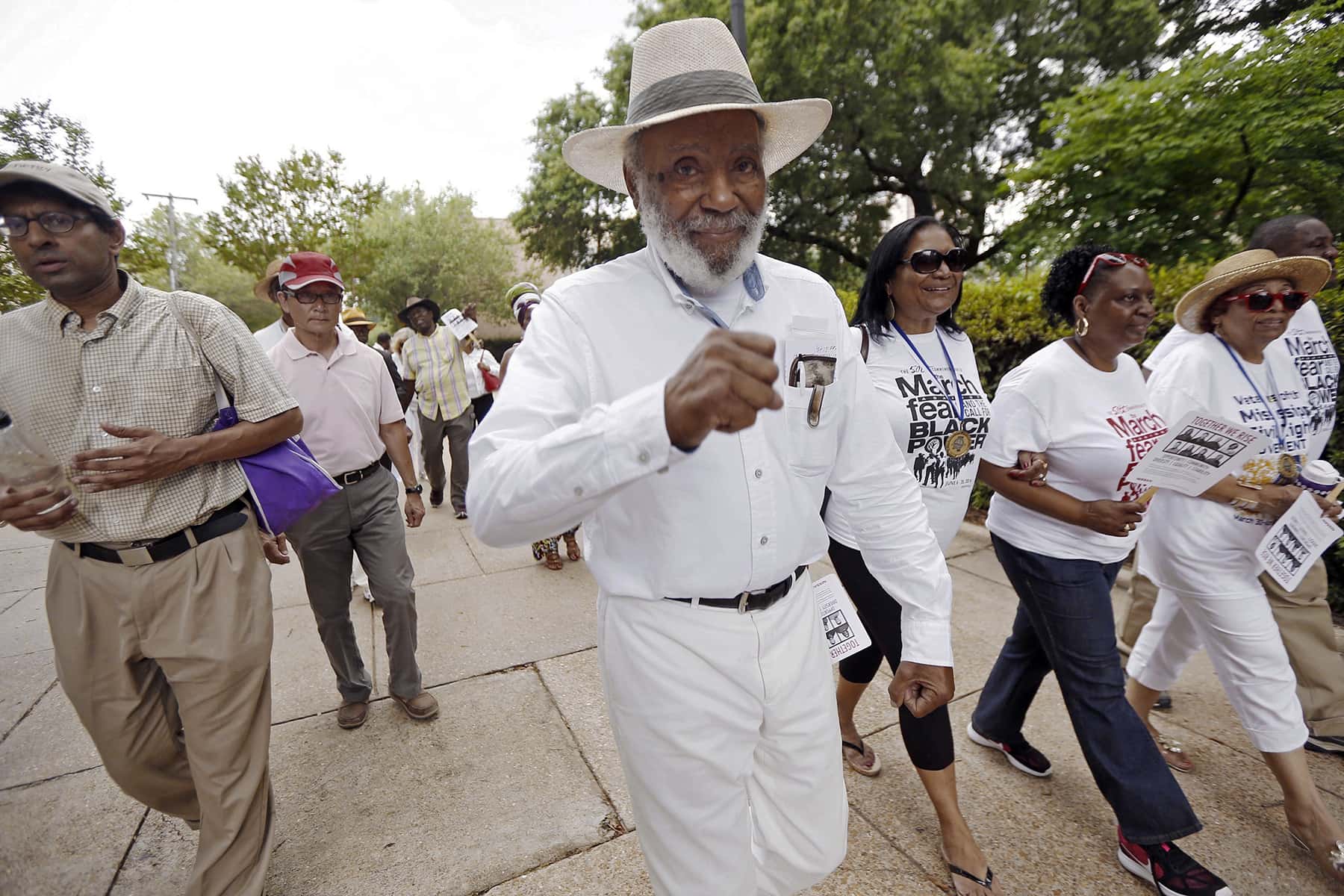

Meredith, who soon turns 88, remains a familiar figure around Jackson. He is one of the elderly regulars at a supermarket’s coffee klatch. He often dons his trademark white suit and a “New Miss” ballcap. Prone to grandiose or quirky statements, he still possesses a certain charisma, informed by his mystical sense of his own God-ordained destiny.

I first encountered Meredith’s paradoxical personality in 2009, during an interview for “Down to the Crossroads,” my narrative history of the Meredith March Against Fear. Since then, I’ve kept wrestling with Meredith’s significance – I wrote the introduction to his reissued memoir “Three Years in Mississippi,” and I’m now collaborating on a graphic history about Meredith and the integration crisis at “Ole Miss.”

Other major figures from the March Against Fear have clear-cut legacies. Martin Luther King Jr. is the moral beacon of a nonviolent movement. Stokely Carmichael, who called for “Black Power” on the march, is a radical icon. Fannie Lou Hamer represents the central role of Black women in the grassroots freedom struggle.

But Meredith? After the march, he faded from view. He did not join any of the major civil rights organizations. His multiple runs for office failed, as did numerous business ventures. By the late 1980s, he seemed to court shock value: He worked for archconservative North Carolina Senator Jesse Helms, and then endorsed Louisiana politician David Duke, a former grand wizard in the Ku Klux Klan.

Yet Meredith also remains a symbol of pride: His statue on the University of Mississippi campus is a rallying symbol for Black students – and also has been a target of racist defacement. Black Mississippians often recognize his heroism. Meredith is difficult to categorize or claim. Those on the political right tend to showcase the rare Black conservative, but Meredith is a vocal critic of American racism, which most conservatives seek to downplay.

Liberals love to celebrate civil rights icons, but Meredith sometimes makes provocative, and even outrageous, statements about the civil rights movement and its leaders. Radicals share his goal of destroying white supremacy, but an old man who preaches old-fashioned morality does not conform to the modern model of an activist.

Streams into a river

The Black freedom struggle has long encompassed people of different ideologies and tactics. Like streams feeding into a river, these political approaches come from distinct sources, but inevitably move in the same direction. In the 1960s, this movement surged forward, in part thanks to Meredith.

He is a complex person – one who might never be fully understood. That’s an important reminder: A movement depends on individual people making individual choices to act in individually specific ways, all in service of a collective goal. The United States is again undergoing a racial reckoning, and again the nation is divided over its direction. It is, moreover, a dangerous moment for democracy. A sizable portion of the electorate believes in conspiracy theories about stolen elections.

In this polarized atmosphere, what can a productive social movement look like?

It has to respect the idealism of the forces demanding change but still speak to broadly shared democratic principles. A powerful movement makes room for contributors who don’t fit neatly into that movement. Sometimes, as in the case of James Meredith, their significance is extraordinary.

Jаck Thоrnеll and Rоgеlіо V. Solіs

Originally published on The Conversation as Shot 55 years ago while marching against racism, James Meredith reminds us that powerful movements can include those with very different ideas

Support evidence-based journalism with a tax-deductible donation today, make a contribution to The Conversation.