The Atlanta History Center opened “Cyclorama: The Big Picture,” featuring the fully restored and historically corrected cyclorama mural “The Battle of Atlanta” on February 22. The colossal work was originally created by the American Panorama Company in Milwaukee by 17 German artists.

At the centerpiece of the new multi-media experience is a 132-year-old hand-painted work of art that stands 49 feet tall, longer than a football field, and weighs 10,000 pounds. The mural is one of only two cycloramas in the United States, making Atlanta home to one of America’s largest historic treasures.

The cycloramas is also an unintended monument to the wonderments of accretion: accretions not merely of paint, but of myth-making, distortion, error, misinterpretation, politics, opportunism, crowd-pleasing, revisionism, marketing, propaganda and cover-up. Only a few years ago, the attraction seemed done for. Attendance was down to stragglers, and the city was hemorrhaging money. The future of the big canvas seemed to be a storage bin somewhere and, after some time, the dustbin.

But then a few folks in Atlanta realized that restoring the painting would not only resurrect one of the more curious visual illusions of the 1880s, but also show a neat timeline of the many shifts in Southern history since Appomattox. It was no mere cyclorama, but the largest palimpsest of Civil War memory to be found anywhere.

Cycloramas were a big popular entertainment once upon a time, and the way it worked was this: Once you entered the big building you would typically proceed to a staircase that you walked up, to a platform located in the dead center of a painting, completely encircling you. The canvas was slightly bowed away from the wall, and the horizon line of the painting’s action was at the viewer’s eye level. As much as a third of the top of the painting was sky painted increasingly dark to the top to create a sense of distance extending away. And the bottom of the canvas would often be packed up against a flooring of dirt with real bushes and maybe guns or campsites, all part of a ground-floor diorama that, in the limited lighting, caused the imagery in the painting to pop in the viewer’s mind as a kind of all-enveloping 3-D sensation.

“It was the virtual reality of its day,” said Gordon Jones, the curator at the Atlanta History Center. The effect was like walking inside one of those stereoscopes, the early View-Masters of that time, that tricked the eye into perceiving space and distance. Standing on that platform was like sinking into this slight illusionary sense—in this case, that you were a commander on a hill taking in the battle at hand.

Beginning in the 1880s, these completely circular paintings started appearing from half a dozen companies, such as the American Panorama Company in Milwaukee, where Atlanta’s canvas was conceived. APC employed more than a dozen German painters, led by a Leipzig native named Friedrich Heine. Cycloramas could depict any great moment in history, but, for a few years in the 1880s, the timing was just right for Civil War battle scenes. A single generation had passed since the end of the Civil War and survivors everywhere were beginning to ask the older family members, what happened in the war?

The Battle of Atlanta Cyclorama was significant because it captured this one moment of the Civil War when everything changed. That midsummer of the war’s fourth year, Northern voters were losing interest, Lincoln’s popularity was sinking, an election was coming up and all news from the battlefields had been bad. Then, in an instant, momentum turned around. Atlanta was defeated, and afterward, General William Tecumseh Sherman turned east for the long march that ended the war.

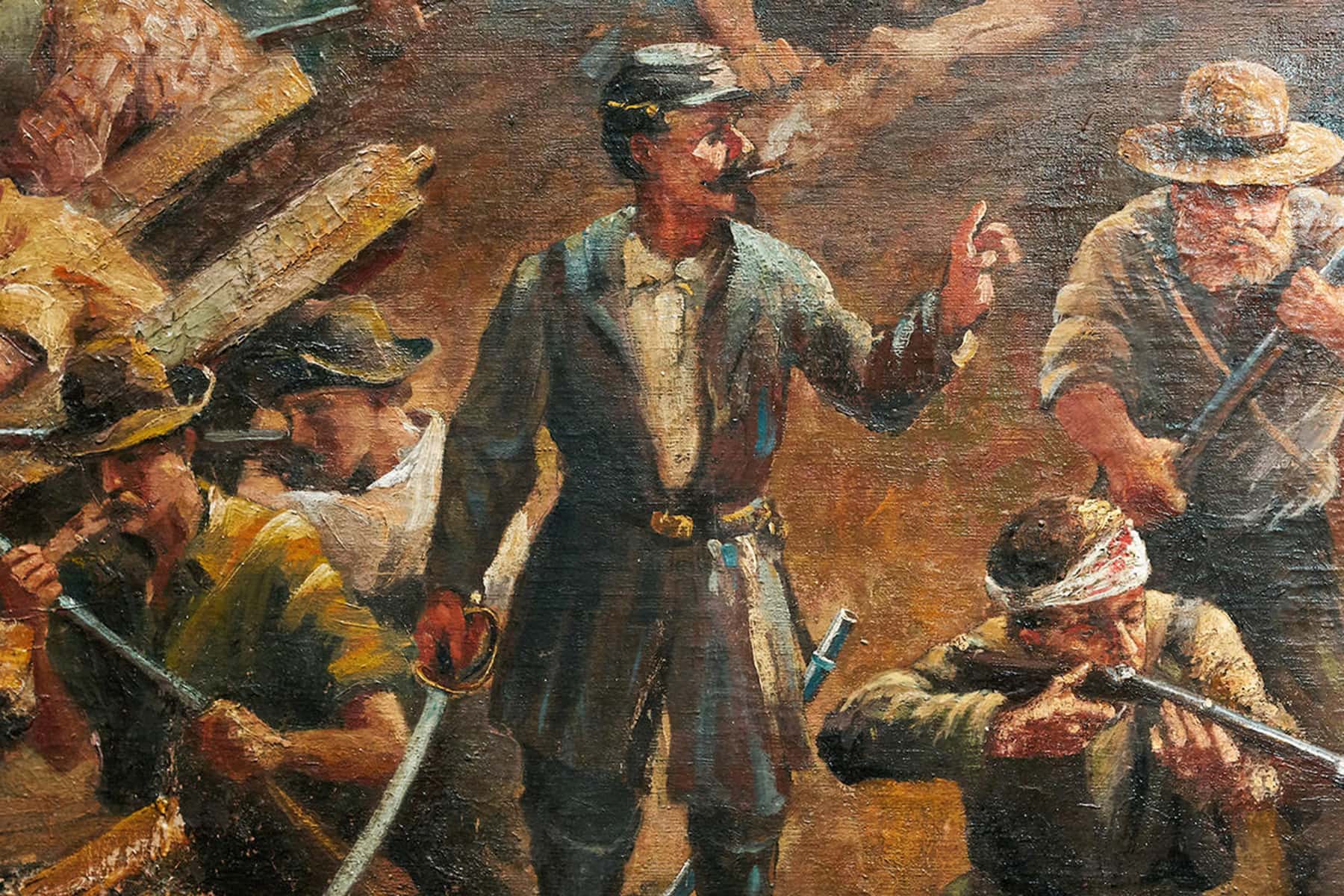

But this battle almost went the other way, especially at one key moment — 4:45 p.m. on July 22, 1864. On the railroad line just outside Atlanta, near a place called the Troup Hurt House, the Union Army had set up a trench line with artillery commanded by Captain Francis DeGress. Rebels broke that line and were heading to take on the Yankee troops until General John “Black Jack” Logan counterattacked and pushed the Confederates back.

“If you are going to have a battle scene, you don’t paint a walkover, right?” explained Jones. “You don’t make it a 42-0 rout. There’s no glory in that. There’s glory when you win by a point with a field goal in the last second of overtime. So, this is that moment.”

The Battle of Atlanta Cyclorama opened in Minneapolis, to a Northern audience in the summer of 1886. A few weeks later, a local newspaper reported that General Sherman declared it to be “the best picture of a battle on exhibition in this country.” Part of its allure was not just the cognitive effect of a 3-D sensation, but also the accuracy of detail. The Milwaukee Germans interviewed lots of Union veterans, they traveled to Atlanta to sketch locations and they spoke to Confederates. In the studio, helping out, was Theodore Davis, war illustrator for Harper’s Weekly, who was on the field that July 22.

The pinpoint accuracies on the canvas were impressive—the weaponry on the field, the uniforms by rank and even details down to the sleigh-like cut of an artillery driver’s saddle. For the vets, there were specific commanders visible among the vast battle confusion, recognizable on the canvas. General James Morgan, General Joseph Lightburn and General James McPherson, lying in the covered-wagon ambulance, where he would die of his wounds.

General Sherman can be spotted on a far hill, overseeing the maneuvers, but the biggest, most recognizable figure is General Black Jack Logan. The painters of the day made him huge because they knew who they were painting for, which is also why there are no recognizable Confederates in the painting. The Cyclorama was a big moneymaker. Crowds packed the rotundas to see a battle, and veterans were full of pride to point out to family members “where I was.”

No one thinks of the late 19th century as a frantic time of new media, but by 1890, magic lantern shows were popular. After only a couple of years the easy money in cycloramas had been made; time for the smart investors to sell off while the getting’s good. The Battle of Atlanta went on the block that year and sold to a Georgian named Paul Atkinson.

Atkinson’s heyday as a promoter coincided with the South’s attempted rewrites of the war, which began to solidify into the first chapter of what we now call the Lost Cause. Slavery might have been the only cause discussed and written about before the war, but down South, that claim had long ago been talked out of the story. Now, the war was about principles of states’ rights and self-determination, but mostly it was about honor.

Atkinson saw a problem with his new acquisition. Because the painting had been done originally for Northern vets, there were a few images that were obviously meant to tip the meaning of the entirety of the canvas. And there was one image in particular that would not jibe with the new Lost Cause view of things. It was that scene, just off from the counterattack, where one could see some Rebels in gray being taken prisoner. And in the hand of one of the Union soldiers was a humbled Confederate flag. POWs, a captured flag, these are the emblems of weakness and dishonor.

So, with some touches of blue paint, Atkinson turned a cowering band of Johnny Rebs into a pack of cowardly Billy Yanks, all running away from the fight. By the time the painting was moved to Atlanta in 1892, the newspaper made it even easier for everybody, announcing the arrival of the new Cyclorama and its depiction of the “only Confederate victory ever painted!” Still, ticket sales were tepid. Atkinson offloaded his mistake to one Atlanta investor who then pawned it off to another; in 1893, the painting was sold for a mere $937. Around the country, the cyclorama fad was over.

As the years passed, the Battle of Atlanta suffered. Roof timbers in one location crashed through and damaged the painting, and when it was finally moved to Grant Park in 1893, it sat outside in the weather for four weeks before being moved into the new building. And when they finally hung the thing, it was discovered the site was too small, so the new owners razored a sizable vertical chunk out of the decaying canvas to make it fit.

The decline of interest in battlefield specifics also segued easily into the latest shift in Lost Cause emphasis. After the collapse of Reconstruction, the two sides of the war finally did heal into a single nation, but the new union was forged by a common embrace of white supremacy. Jim Crow laws were passed in the South and segregation became the accepted way, from Maine to Florida and straight across to California. Every surge of resistance from black Americans was met with a counterassault of grotesque violence. Beginning roughly in 1890, an African-American was lynched, burned alive, or mutilated every week for the next 50 years.

The rearrangement of a nation founded on the idea of equality into a country with a permanent second class meant re-domesticating the slaveholding planter philosophy of how things should be. Blacks would be relegated to a segregated economy, but this time, a more folksy sense of supremacy was also promulgated, a kind of Southern lifestyle every region of America could enjoy. The popularization of the Confederate rectangular Navy Jack flag would serve to rebrand the South as this distinctive place, home of a new easygoing racism. Now, everyone could have an Aunt Jemima cook you pancakes in the morning, and faithful retainer Uncle Ben serve the converted rice at dinner. They were right there on the boxes at the local grocery, available for purchase.

This new story also meant reshaping the forced-labor camp of cotton production into the romantic splendor of the plantation mansion, rebuilt as a magnolia Arcadia of neo-Georgian architecture. No media event was more responsible for cementing these new factoids into the minds of Americans than “Gone With the Wind” — a 1939 movie that distills the South into a cozy racial lifestyle while utterly marginalizing the Civil War. In the movie’s four-hour running time, there is a not a single battle scene.

The technical adviser largely responsible for the entire look and feel of that movie was Wilbur Kurtz, an Illinois-born painter who moved to Atlanta as a young man. He married a Confederate officer’s daughter. Like so many eager transplants, Kurtz became more Southern than any other Southerner. And in those years before “Gone With the Wind” was released, during the 1930s, the city of Atlanta asked Wilbur Kurtz to restore the dilapidated Cyclorama. So, for Kurtz, restoring the Cyclorama also meant brightening things up here and there.

In the canvas, for reasons lost to history, there had been a few flags showing St. Andrew’s Cross, the red cross on the white field that eventually became the state flag of Alabama. Kurtz overpainted them with the new signifier of Southern heritage —t he rectangular Navy Jack of the Confederate States. By the end, he added 15 of the Navy Jack flags, and painted in nearly a dozen new Confederate soldiers.

Then, a funny thing happened on the way to the future: the Voting Rights Act. By the early 1970s, certain city council members were pushing to have the Battle of Atlanta, properly understood as a Confederate victory, taken to Stone Mountain to become part of a neo-Confederate relic jamboree that is hosted there. But by then, the mayor of Atlanta was Maynard Jackson, the first African-American to hold that office, and he had an “Emperor Has No Clothes” moment. Amid new legislation to relocate the canvas, he simply looked at the painting, saw what it was, and said so out loud.

“The Cyclorama depicts the Battle of Atlanta, a battle that the right side won,” he explained in 1979, “a battle that helped free my ancestors. I’ll make sure that that depiction is saved.”

By 2011, though, the Cyclorama was again in shabby condition, a moth-eaten relic that a new mayor wanted to trash. “He put it on his list of city-owned assets that he viewed as white elephants,” said Sheffield Hale, who chaired the committee to decide how to dispose of things like the Cyclorama.

Downtown was now host to all kinds of buzzy attractions invoking the New Atlanta. There were recommendations to hang the old canvas near Underground Atlanta, the shopping district, or maybe finally put it in that storage bin, wait a few decades, and throw it away. That story hit the Atlanta Constitution on a Sunday in 2013 and one of the city’s most successful real estate moguls, Lloyd Whitaker, was reading the paper just before heading off to church. Around that same time Hale took a job at the Atlanta History Center, located in the city’s affluent Buckhead district. Whitaker offered $10 million as a lead legacy, and an incentive to raise even more money. Hale recognized right away how a new context for a cheesy 1880 spectacle could be created.

“This was not an attraction, this was an artifact,” said Gordon Jones, the History Center curator. “We ended up raising $25 million more to construct the building, restore the painting and do the exhibits. We had the ability to really deal with the history of the painting and the Lost Cause and all that is wrapped up in the irony of the painting — and turn it into a different object.”

Hale and Jones restored the painting according to the documentary history recorded by the German artists in 1886. They want to recapture the original optical effect as well, with attention to scale and lighting. But they also filled back in elements that had been snipped out, painted over or otherwise altered over the years. Those Confederate captives, reimagined as fleeing Unionists by Atkinson, are again be shown as prisoners. And another image added by Atkinson, that of a Union flag ground into the mud, was expunged.

“The hierarchy of our thinking was to restore the illusion intended by the artists,” Jones said, “But throughout the canvas there were exceptions that were allowed to remain.”

Jack Hitt

Joshua Rashaad McFadden and Wisconsin Historical Society

Edited for length and originally published by the Smithsonian as Atlanta’s famed cyclorama mural will tell the truth about the Civil War once again