By Samantha Hill, 2019 – 2021 Joyce Bock Fellow at the William L. Clements Library at the University of Michigan and current graduate student at U-M School of Information, University of Michigan; and Janette Greenwood, Professor of History, Clark University

Frederick Douglass is perhaps best known as an abolitionist and intellectual. But he was also the most photographed American of the 19th century. And he encouraged the use of photography to promote social change for Black equality.

In that spirit, this article examines different ways Black Americans from the 19th century used photography as a tool for self-empowerment and social change, and how that legacy extends into today.

Black studio portraits

Speaking about how accessible photography had become during his time, Douglass once stated: “What was once the special and exclusive luxury of the rich and great is now the privilege of all. The humblest servant girl may now possess a picture of herself such as the wealth of kings could not purchase fifty years ago.”

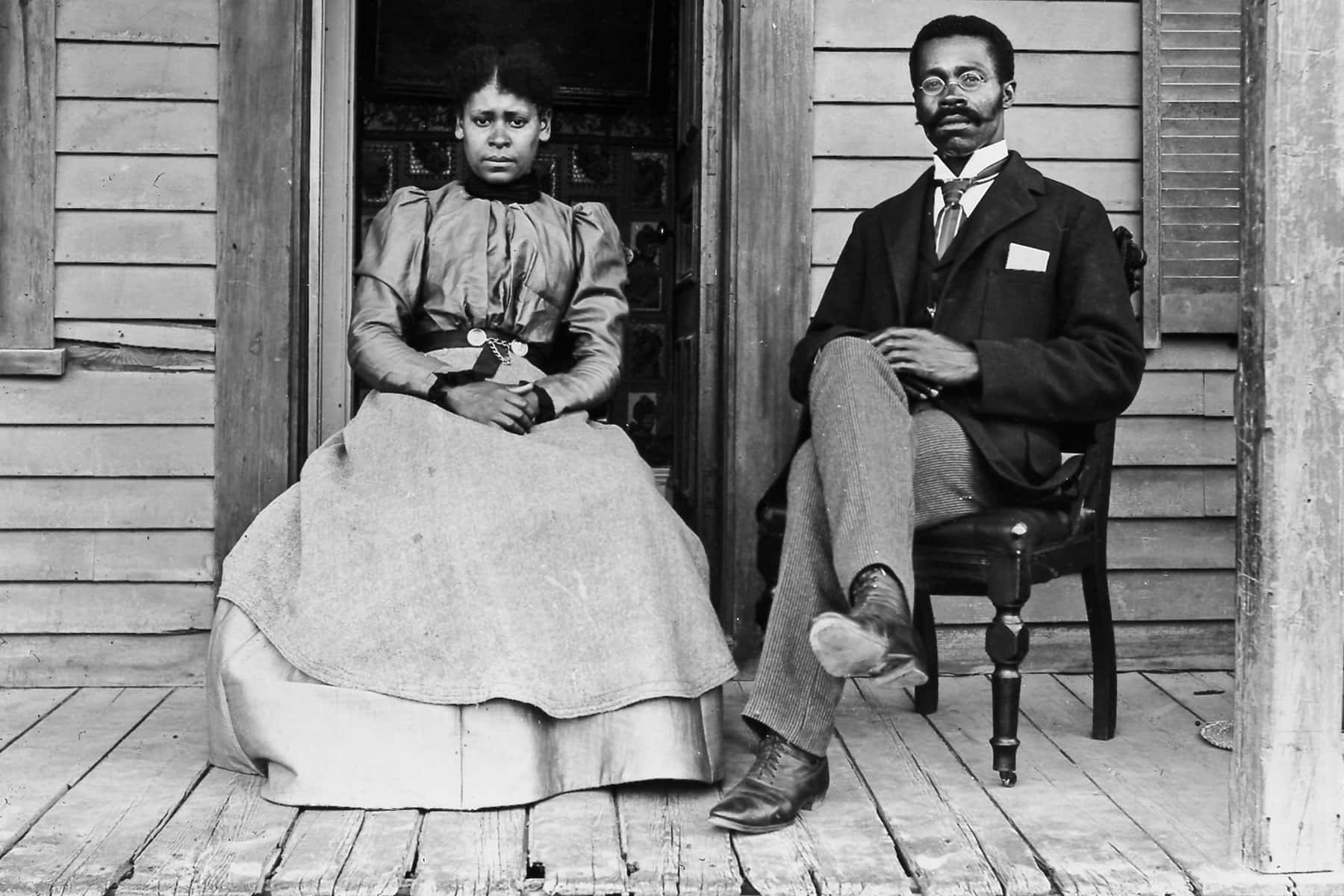

To pose for a photograph became an empowering act for African Americans. It served as a way to counteract racist caricatures that distort facial features and mocked Black society. African Americans in urban and rural settings participated in photography to demonstrate dignity in the Black experience.

The first successful form of photography was the daguerreotype, an image printed on polished silver-plated copper. The invention of carte de visite photographs, followed by cabinet cards, changed the culture of photography because the process allowed photographers to print images on paper. Cartes de visite are portraits the size of a business card with several copies printed on a single sheet. The change from printing images on metal to printing on paper made them more affordable to produce, and anyone could commission a portrait.

Collecting kinship: Arabella Chapman albums

During Victorian times, it was fashionable for people to exchange cartes de visite with loved ones and collect them from visitors. Arabella Chapman, an African American music teacher from Albany, New York, assembled two cartes de visite photo albums. The first was a private album of family pictures, while the other featured friends and political figures for public viewing. The creation of each book allowed Chapman to store and share her photographs as intimate keepsakes.

Innovative entrepreneurs: The Goodridge Brothers

When photography became a viable business, African Americans started their own photography studios in different locations across the country. The Goodridge Brothers established one of the earliest Black photography studios in 1847. The business, opened first in York, Pennsylvania, moved to Saginaw, Michigan in 1863. The brothers – Glenalvin, Wallace and William – were known for producing studio portraits using a variety of photographic techniques. They also produced documentary photography printed on stereo cards to create 3D images.

Saginaw, Michigan, was an expanding settlement, and the brothers photographed new buildings in the town. They also documented natural disasters in the area. Photographers would capture 3D images of fires, floods and other destructive occurrences to record the impact of the event before the town rebuilt the area.

Documenting communities: Harvey C. Jackson

The development of Black photography studios allowed communities greater control to style images that authentically reflected Black life. Harvey C. Jackson established Detroit’s first Black-owned photography studio in 1915. He collaborated with communities to create cinematic scenes of important events. In one photo, Jackson documents a mortgage-burning celebration at the Phyllis Wheatley Home, established in 1897. Its mission was to improve the status of Black women and the elderly by providing lodging and services.

Mortgage-burning ceremonies are a tradition churches observe to commemorate their last mortgage payment. Harvey Jackson documented this occasion with each person holding a string attached to the mortgage to connect each person in burning the document. African Americans’ engagement with photography in the 19th century began a tradition for Black photographers’ use of photography today to promote social change. African Americans, whether they are in front or behind the camera, create empowering images that define the beauty and resilience contained within the Black experience.

A record of everyday Black Americans

For decades, the Black family has been denigrated as dysfunctional. When mass media exploded in the late 19th century, degrading images of Black Americans – as inferior, clownish and dangerous – saturated nearly every aspect of popular culture, from music to advertising. The evolution of radio, film and television in the 20th century only amplified demeaning images, providing “proof” to white Americans of Black inferiority and a justification for denying them their rights.

Today, many of these same tired images persist and continue to feed baseless perceptions. A 2017 study showed that the news media continue to “inaccurately portray Black families as more poor, criminal and unstable than white families.” When those malicious images first started to proliferate, Black Americans found an especially effective way to resist. They seized upon the camera to represent themselves, using photographs to depict who they really were. Seemingly a “magical instrument” for “the displaced and marginalized,” as critic bell hooks writes, the camera provided “immediate intervention” to counter the injurious images used to deny them their rightful place in American society.

In 2013, a historian and collector named Frank Morrill discovered over 230 portraits of people of color among the 5,300 glass negatives of photographer William Bullard that he owned. These portraits illustrate the ways that ordinary, working-class families used the camera to represent themselves in their full humanity. Bullard, a white neighbor of most of the people he photographed in Worcester, made these portraits from 1897 to 1917. Their images defy stereotypes of dysfunction by portraying the vitality of Black family life just a few decades after emancipation.

As Bullard was making his portraits, sociologist and civil rights activist W.E.B. Du Bois was curating a photographic exhibition for the 1900 Paris Exposition. Du Bois sought to showcase Black achievement to the rest of the world, and his images featured middle-class and elite Black Americans, often in a studio setting and without specific identification. Bullard’s portraits, on the other hand, are extraordinary because they capture common people on their porches, backyards and parlors. Moreover, most of the families can be identified, allowing their stories to be told.

Symbols of resilience and aspiration

The existence of these family units was an achievement in its own right. At the time Bullard made his portraits, slavery and family separations remained a traumatic memory for many of his subjects. As a result, family portraits were especially significant. They testified to the achievements and aspirations of Black Americans and the resilience of their kinship networks.

And for a people whose history had so often been obliterated, the photographs provided an opportunity to preserve their stories for future generations. In 1900, Rose, Edward and Abraham Perkins posed for Bullard in their Worcester backyard. Born into slavery in South Carolina, the three siblings and other family members had settled on former plantation land that Edward managed to purchase only a few years after emancipation.

But their dream of life as independent farmers ended with the demise of Reconstruction. A backlash of terror against the state’s Black population once again ushered in the rule of White Supremacists. Caught in the vice of declining cotton prices and an economic depression, Edward lost his land. With their hopes for new lives in the South demolished, Edward and his wife Celia made the decision to seek a more complete freedom in the North.

They made their way to Worcester in 1879; soon Rose, Abraham and many other family members followed. As refugees of terrorism and economic disaster, the siblings, in their portrait, embody triumph and perseverance, and commemorate the tenacity of family ties that stayed intact through slavery, emancipation and migration.

Conveying respectability and stability

Other photos portray flourishing young families claiming their place in American society. The subjects present themselves as ordinary, upstanding Americans who share the same values, tastes and aspirations as their contemporaries. In 1904, Thomas, a Virginia native, and Margaret Dillon, born near Boston, posed with their three children in the parlor of their home. Legs crossed and hands in the pockets of a stylish suit, Thomas appears as a proud patriarch. Margaret, with a smile on her face and her luxuriant skirt cascading to the floor, radiates maternal love and decorum. She holds their baby as two older, well-dressed children stand between mother and father.

Flowered wallpaper, lace curtains and framed paintings signify a well-appointed home. A poster on the wall commemorates President Theodore Roosevelt’s visit to the city in 1902, suggesting the family’s engagement in politics and local affairs. In this tableau of respectability and stability, the Dillons defy nearly every stereotype of the dysfunctional Black family. Although they labored for white families – Thomas as a coachman and Margaret as a domestic servant – and had yet to achieve middle-class security, their portrait brims with aspiration.

Refuting stereotypes of Black men

When the Dillons and others posed for Bullard, lynchings of Black men were spiking in the U.S. The brutish “Black beast rapist” – an archetype invented in the white South during Reconstruction – often served as justification for these murders. Postcards of lynchings were widely circulated, along with “humorous” postcards and cartoons featuring Black men stealing chickens and watermelons.

In the midst of this attack on Black manhood, some families centered their portraits on fathers and children. Around 1904, Raymond Schuyler, a railroad worker originally from upstate New York, had his portrait made with his four children in a snow-covered park. Playfully sitting on a child’s sled, with his arms encircling one of his young daughters, Schuyler personifies a benevolent, gentle masculinity. In another image, a father poses with his baby on his lap, his large hands securely holding his child. He wears the uniform of the Knights of Pythias, a fraternal organization that espouses the values of responsibility, community and family.

The quiet resistance of the family photograph

As Black men battled claims of their inherent criminality, Black women fought a dualistic stereotype – that of the promiscuous “Jezebel” or servile “Mammy.” Black women fought these images by presenting themselves with respectability and decorum. Take Jennie Bradley Johnson, who posed with her two stylishly dressed daughters, May and Jennie. Seated in a lush garden, surrounded by hydrangeas, Johnson conveys maternal warmth and modesty. Recently widowed and facing the burden of raising her family alone on a laundress’s wages, she nevertheless projects strength and endurance in the face of loss.

Historical portraits provide an invaluable means to enter the distant past. And other photographers have continued the tradition. In 2017, photographer Zun Lee unveiled his exhibition “Fade Resistance,” made up of “orphaned” Polaroids from the 20th century that Lee discovered at yard sales and on eBay. The Black Americans in the photographs pose proudly with their cars, dress up for Easter and play with their kids. Like Bullard’s portraits, Lee’s found family images are, as Lee wrote, a reminder that “there is a vivid history of Black visual self-representation that offers an eerily contemporary counter-narrative to mainstream distortion and erasure.”

Demonstrating the chasm between stereotype and reality, these Black family portraits reveal the ways in which ordinary hard-working Black families have long been rendered invisible in mainstream American culture. They reveal the common goals shared by all American families: the desire for stability and security, and the chance to nurture and support children so that they can have a better future.

Courtesy of Frank Morrill, Clark University, Worcester Art Museum, and William L. Clements Library

Originally published on The Conversation as How Black people in the 19th century used photography as a tool for social change and How Black Americans used portraits and family photographs to defy stereotypes

Support evidence-based journalism with a tax-deductible donation today, make a contribution to The Conversation.