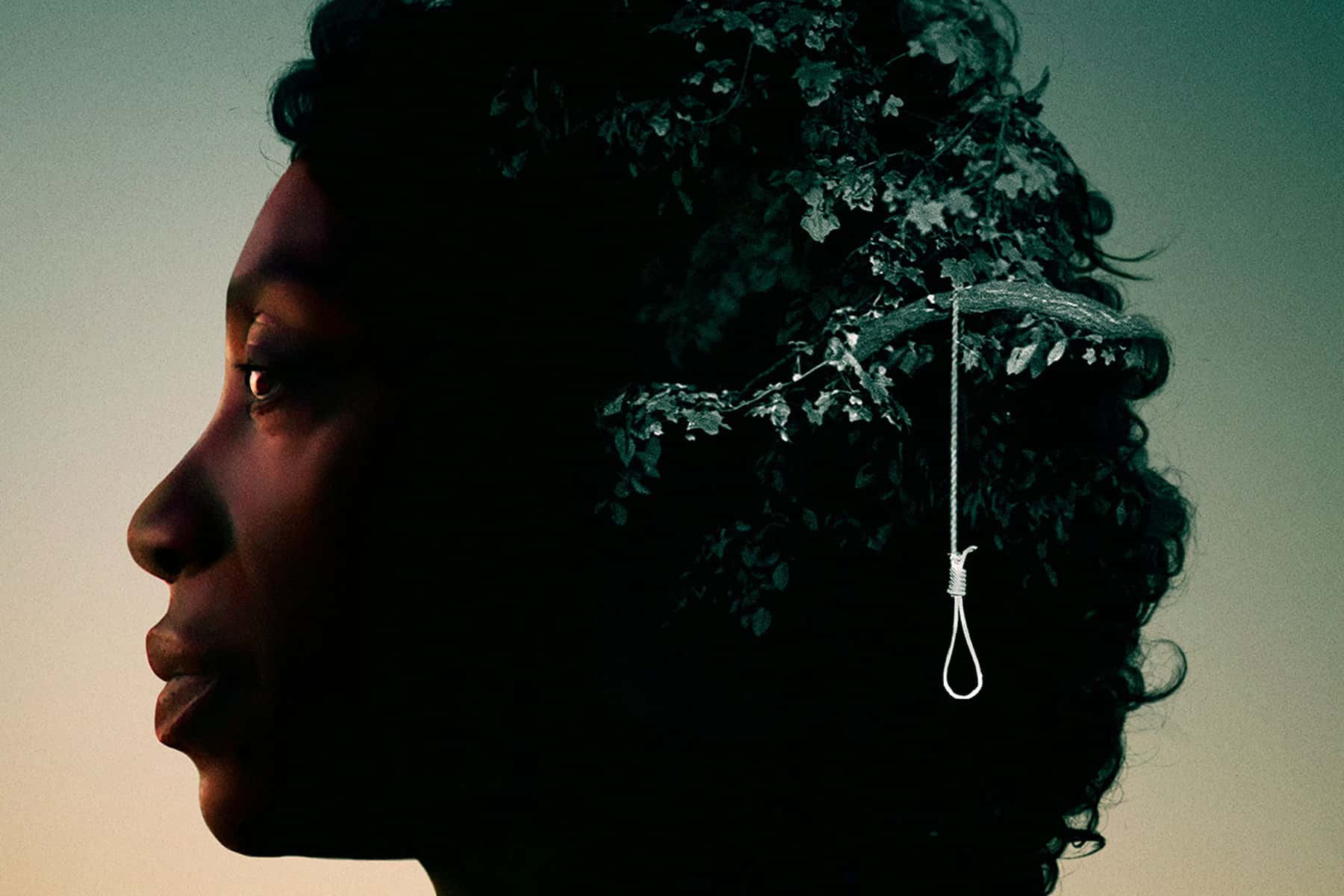

The last time director Jacqueline Olive visited Milwaukee, her film “Always in Season” was still in production. Recently she returned to show the finished work at the Milwaukee Film Festival. The devastating documentary shares a history of lynching tied to the mysterious death of a black teen, who was found hanging from a swing in 2014.

In the summer of 2014, Jacqueline Olive was preparing to wrap up her documentary film on America’s gruesome history of racial lynching, having devoted five years to chronicling its corrosive impact in the south and across the country.

Just as she was about to start editing, news reached her of a disturbing event in the small North Carolina town of Bladenboro. In the early hours of 29 August 2014, a 17-year-old African American boy named Lennon Lacy had been found hanging from a swing set in an all-white trailer park about a quarter of a mile from his home.

Within days of his body being found, the local police chief had declared the tragedy to be a suicide. But for Lennon’s mother, Claudia Lacy, that rush to judgment was not enough.

Why had there been no thorough investigation into her son’s death, she demanded to know? Where was the evidence that this happy and popular boy had intended to take his own life? Why was Lennon wearing unfamiliar shoes a size smaller than his own when he died, and whose belts were those from which he had been hanging?

Bringing the story to nationwide attention for the first time in October 2014, Lacy began to pose a terrible question: had her son been the victim of a modern-day lynching? For Olive, herself a black woman from Mississippi, the death of Lennon resonated personally.

“My son was 17, Lennon’s age,” said Olive. “I was overwhelmed by what it must have meant to Claudia to lose her son in a way that was so tied to our historical trauma. I couldn’t imagine the depth of grief.”

Professionally, Lennon’s death resonated too. The more Olive learnt about what had happened, the more she saw parallels with her earlier work on lynching, and the more she was convinced that she had to rethink her movie.

“I started to appreciate that Bladenboro was very much coming out of the history of racial terrorism and connected to what I had been doing,” she said. “Lennon’s story was key to the narrative of the film.”

It is testament to the herculean effort that goes into an award-winning documentary that within weeks Olive had decided to pull up stakes in California and relocate to North Carolina to begin a whole new phase of filming in Bladenboro. The movie that she had thought was nearing completion was extended by a further five years – bringing its total gestation to a decade.

The result is “Always in Season,” an 89-minute feature that won the special jury award for moral urgency at Sundance in January. Now on release across the US, audiences will be exposed to a film that is both a homage to Lennon Lacy and a critique of America’s rotten racial core, weaving the two together through an exploration of blurred memory, denial, obfuscation, betrayal and loss.

“Claudia Lacy and everybody in Bladenboro are living without answers,” Olive said. “They are living with rumors and speculation, in just the same way that people in towns that have been dealing with historic lynching still don’t have answers.”

Since Lennon’s death, Lacy has tested herself and emerged as steely campaigner who succeeded in forcing a statewide investigation and eventually secured a full FBI investigation into the tragedy. Where has she found the strength to keep going, despite so many knockbacks? She cited her Christian faith, as well as the solace drawn from meeting other mothers who have suffered similar losses.

In particular, she was grateful to team up with Sybrina Fulton, mother of slain teenager Trayvon Martin, and Gwen Carr, mother of Eric Garner whose cry of “I can’t breathe” while in a police chokehold became a national call to action.

“We have a connection, as black mothers. There’s no way you can detach yourself from that,” Lacy said.

Having Olive ride into town with her camera crew in tow also became a source of strength for Lacy. It helped her perceive her home town, with its population of less than 2,000, in a new light.

Through the film-maker’s eyes, Lacy came to appreciate how sealed off Bladenboro was from the rest of the world, how myopic in its mindset. “The town is like a box,” she said. “Things don’t get out of that box, they are supposed to stay right there in that box. Letting Jackie into the story helped, because she asked the questions that people didn’t want to answer.”

Both women encountered hostility when they began their inquiries. Lacy had neighbors come up to her asking her why she was stirring things up, encouraging outsiders to come into town to tell them how to behave. Even some of her own relatives advised her to let go of the fight for justice for Lennon. She had done enough, they said, there was nothing more she could do.

She didn’t listen. “I’m Lennon’s mother. I carried him nine months. So how can anyone question me about when I should give up on what happened to my son?”

Olive also experienced a chilly reception in Bladenboro. When she was filming at the swing set in the center of the trailer park where Lennon died, a white man drove up in a pickup truck asking what she was doing. He had a shotgun strung up on a rack behind the driver’s seat.

Black residents of the town would often whisper as she was interviewing them outside their homes to benefit from natural light, forcing her to move the filming inside. “That talked to me,” the director said. “The fear was totally understandable – those old power dynamics are still in place.”

Here was another stark parallel with the work she had already done on historical lynching. When Olive first began filming in communities in 2010 very few people – white or black – were willing to face up to the fact that their own town had such a dark past.

“Most communities were in denial,” Olive said. “These were places where half the town would have turned up in thousands to a lynching, openly cheering it on. Yet immediately there was a cover-up that created a cognitive dissonance that was passed through the generations and is still deeply present today.”

“Always in Season” is unsparing in the way it depicts racial lynching. It includes graphic footage of re-enactments of the events, focusing on the 1946 Moore’s Ford lynchings in Monroe, Georgia, in which two married African American couples were killed and hanged from a bridge.

To this day, the underside of the bridge still displays graffiti advertising the KKK and proclaiming “No Niggers Allowed”. Also, to this day, nobody involved in the quadruple murders has ever been charged.

The film also reproduces harrowing images from the scenes of public lynchings, many of which were held in broad daylight on the courthouse lawn. Olive and the film’s editor, Don Bernier, linger over the smiling faces of white men, women and children as the burnt and mutilated limbs of victims hang over them.

Olive accepted that her film will challenge audiences, but she stressed that the editing choices were intentional. “We wanted to look closely at how whites show up in this story, to focus on the spectators rather than the victims. That can be difficult, certainly, it can lead to feelings of defensiveness and guilt – but we thought it provides important lessons in this very American story.”

“Always in Season” is controversial too in its central framing in which the death of Lennon is linked unquestioningly to America’s historical lynching. The teenager’s death has never been ruled a homicide: the FBI concluded its investigation in June 2016 saying they had found no evidence of a hate crime.

How did the film director square that official analysis with her decision to connect Lennon to the horrors of America’s past? “I think it speaks to the question of whose truth is valid,” Olive said. “Is it documentation, or is it people’s generational understanding and memory around these stories. I’ve done the research to understand that a lot of evidence around lynching is never documented.”

For her part, Lacy said she remains “100% certain” her son was murdered. Official paths may now be closed to her, but she has not given up her fight for answers.

There has been no closure for her, and perhaps there never will be. But Lacy said that watching “Always in Season” provides its own kind of closure: “The documentary allows Lennon’s story to be told. His life was not lost for nothing.”

Claudia described what it was like sitting through the film the first time she saw it, at a private viewing attended only by Claudia, her son Pierre and Olive. “It was very emotional,” she said, her eyes brimming.

“This is not how a 17-year-old’s life should end. But it did, and now it’s shedding light on a deep shame that must be dealt with. It’s time for it to come out. It’s time.”

Ed Pilkington

Multitude Films and Lee Matz

Originally published on The Guardian as Always in Season: behind the painful film about lynching in America

Help deliver the independent journalism that the world needs, make a contribution of support to The Guardian.