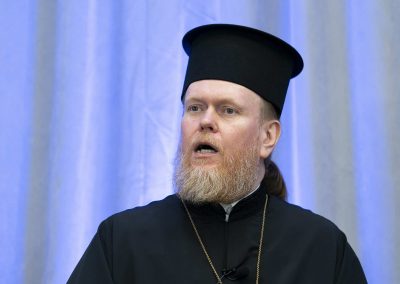

Like other Christian, Jewish and Muslim clergy in a delegation of Ukrainian interfaith leaders visiting the United States, Bishop Ivan Rusyn has a succinct message: “Please, hear our cry.”

The deputy senior bishop of the Ukrainian Evangelical Church, a Protestant denomination, said that since the February 2022 Russian invasion, some of his church’s pastors have been killed, and its seminary has been attacked by missiles. In Russian-occupied areas, he said, the church has been forced underground.

“To make it short, it has been hell” in occupied areas, Rusyn said during a visit on October 30 by a delegation of the All Ukrainian Council of Churches and Religious Organizations at the U.S. Institute of Peace.

“We are not speaking about social marginalization,” he said. “We are speaking about people being murdered because they have different faith.”

He and the other clergy thanked the United States for its aid to Ukraine and ask for continued support. Group members said Russian occupiers are snuffing out religious and other freedoms in areas of Ukraine under Russian control.

“This war made every Ukrainian my neighbor,” Rusyn said during the peace institute forum.

The delegation sought to show they are largely united across religious lines. And they wanted to allay concerns about a draft law seen as targeting one branch of Orthodox Christianity, and asserted that religious freedom is thriving in Ukraine — in contrast with Russian-occupied areas, where they said religious persecution is widespread.

“We are eyewitnesses of Russian atrocities going on in our country,” said Metropolitan Yevstratiy Zoria, a representative of the Orthodox Church of Ukraine.

The U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom said in a July report that Russian military forces “have frequently damaged and destroyed religious buildings and other sites and killed or injured those sheltering or worshiping in these places,” and it said they have “abducted and tortured religious leaders.”

UNESCO reported in October that it has verified damage to 124 religious sites in Ukraine, in addition to other cultural sites.

The delegation’s visit is including numerous stops at places ranging from the U.S. State Department to the Houston medical community to thank participants who have brought medical aid to Ukraine.

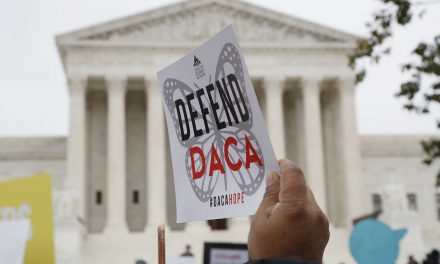

They also tried to allay fears about the religious climate in Ukraine itself. The Ukrainian parliament gave preliminary approval earlier this month to a bill seen as essentially banning the similarly named, but separate Ukrainian Orthodox Church because of its ties to the Orthodox Patriarch of Moscow, who has strongly supported the Russian invasion. A final vote is pending.

The law doesn’t name a specific church but bans activities of any religious organization affiliated with management centers in an aggressor state.

The Ukrainian Orthodox Church has declared its independence from Moscow and proclaimed its loyalty to Ukraine, but a government study commission contended that the UOC remains a structural unit of the Russian Orthodox Church.

The other separate, but similarly-named church, Orthodox Church of Ukraine, was officially recognized as independent by Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew of Constantinople in 2019, but the Russian church has disputed the legitimacy of that recognition.

Metropolitan Zoria, a spokesperson of the Orthodox Church of Ukraine, said the goal of the draft law is to “protect religious freedom from being instrumentalized by the Kremlin’s dictatorship.”

He and other delegation members said there’s widespread religious freedom in Ukraine, in contrast to Russian-controlled areas, where “if you’re not loyal to a Russian government, you have no rights,” said Zoria, deputy head of the department for external church relations for the OCU.

Zoria decried statements by Moscow Patriarch Kirill of the Russian Orthodox Church, who has strongly supported the war as part of a metaphysical battle against Western liberalism and has said the Russian war dead have their sins forgiven.

“These public blessings of Russian atrocities,” Zoria said, are part of “a policy to justify the elimination of Ukrainian identity.”

Rabbi Yaakov Dov Bleich said that members of religious minorities had concerns about the law, wanting to be sure it would not be a precedent used against other religious groups. But he said he sees the need for the law. He said every religious group is at risk of being coopted by the Russians, saying he rejected overtures of Russian agents in 2005 to pay him for control and influence over Jewish life in Ukraine.

“Obviously, we’re all nervous about it,” Bleich, chief rabbi of Kyiv and Ukraine, said of the draft law. “But at the end of the day, Ukraine has to survive, Ukraine has to thrive as a democracy, and it will not happen if parts of it are going to be controlled from the enemy state.”

Members of the delegation said at the forum on October 30 that they are aware that continued U.S. aid to Ukraine faces skepticism from some American conservatives, including some American Christians who perceive Russian President Vladimir Putin as a defender of traditional values.

Rusyn said he hopes to have dialogue with fellow evangelicals in America. They need to know that in Russian-controlled areas of Ukraine, “their fellow evangelical believers are being killed on an every-day basis,” he said.

Rusyn said Ukrainian Christians know what religious repression looks like — they endured 70 years of it under Soviet rule — and that “now we do have this freedom” in Ukraine

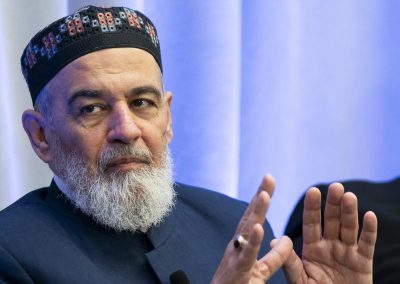

Akhmed Tamim, supreme mufti of Ukraine and head of the Religious Administration of Ukrainian Muslims, echoed other members of the delegation.

“We don’t want anybody to destroy Ukraine like Yugoslavia,” he said. “We are part of the Ukrainian community. We defend our land.”