After its searches of holy sites belonging to Ukraine’s historic Orthodox church, the nation’s security agency posted photos of evidence it recovered, which included rubles, Russian passports and leaflets with messages from the Moscow patriarch.

Supporters and detractors of the church have debated whether such items are innocuous, or increase suspicions that the church is a nest of pro-Russian propaganda and intelligence-gathering.

What is unambiguous are other photos shared by the agency, known as the SBU, posted as recently as December 7 — some showing an armed Ukrainian officer standing outside a church building, others showing brawny, camouflaged officers questioning clerics in long beards and cassocks.

They illustrate the increased pressure the Ukrainian government is putting on the Ukrainian Orthodox Church, with its centuries-old ties to Moscow, as the brutal Russian invasion slogs into the 10th month of a war that has had religious dimensions from the start.

President Volodymyr Zelenskyy on December 2 announced measures primarily targeting the Ukrainian Orthodox Church, which is one of two major Orthodox churches in Ukraine following a 2019 schism. Even though the UOC declared independence from Moscow in May, such a declaration is easier spoken than accomplished amid the complexities of Eastern Orthodox Christianity. Besides, many Ukrainians don’t believe it’s really free from Moscow.

President Zelenskyy called for legislation that would forbid “religious organizations affiliated with centers of influence in the Russian Federation to operate in Ukraine.”

He also wants a review of the “canonical” connection between the UOC and the Moscow Patriarchate, the center of the Russian Orthodox Church, and of the status of the revered, millennium-old Pechersk-Lavra monastery in Kyiv, now government-owned but largely used by the Ukrainian Orthodox Church.

The government also placed sanctions on its abbot, another wealthy churchman and several bishops in Russia or Russian-held parts of Ukraine.

“We will ensure, in particular, spiritual independence,” President Zelenskyy said. “We will never allow anyone to build an empire inside the Ukrainian soul.”

The matter is testing whether the young republic can survive Russia’s attacks – and as a pluralistic state respecting freedom of conscience. It also raises the stakes as the two rival Orthodox churches vie for the loyalties of the nation’s majority Orthodox population and for church properties.

“Maybe it is hard psychologically that this is happening now in monasteries and temples,” said Metropolitan Oleksandr of the Transfiguration of Jesus Orthodox Cathedral in Kyiv. He spoke to reporters by candlelight as portraits of church elders looked on, amid controlled power outages.

“But I think it is better that there will be searches than some people who help guide enemy missiles.”

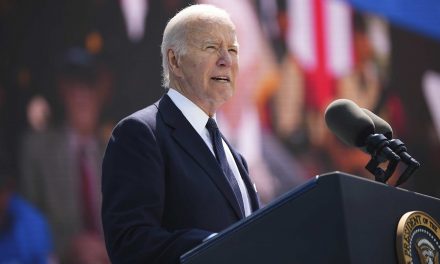

The Biden administration said it supports Ukraine’s self-defense while expecting it to comply with international law on protecting freedom of religion.

The Ukrainian Orthodox Church has been loyal to the Moscow patriarch since the 17th century.

In 2019, the rival Orthodox Church of Ukraine received recognition from the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople. But Moscow’s and most other Orthodox patriarchs refused to accept that designation.

Russia’s February invasion underscored the alliance between President Vladimir Putin and Moscow Patriarch Kirill, who said Russia was defending Ukrainians from Western liberalism and its “gay parades.”

From the start, the Ukrainian Orthodox Church denounced the invasion and such justifications, backing Ukraine. In May, the church declared its own “self-sufficiency and independence” from Moscow.

While that sounds definitive, the church did not declare itself “autocephalous” – the Orthodox gold standard of independence. That was in part to maintain ties with other countries’ Orthodox churches that had not agreed to such a status.

The UOC did give Moscow a liturgical cold shoulder by dropping the commemoration of Kirill as its leader in public worship and blessing its own sacramental oil rather than use Moscow’s supply.

These acts represent “an enormous step” in the Orthodox world even if they seem arcane, said Elizabeth Prodromou, a fellow for Atlantic Council’s Eurasia Center.

Even so, some see the Ukrainian Orthodox Church as still aligned with Moscow and the “Russian world” concept of political and spiritual unity of Russians, Ukrainians, and Belarussians.

“What the people want is for the church to make very clear who they are, who they are for,” said Archimandrite Cyril Hovorun, a Ukraine native and professor of ecclesiology, international relations and ecumenism at Sankt Ignatios College, University College Stockholm.

Ukraine’s counter-intelligence service, known as the SBU, searched the landmark Pechersk Lavra complex last month, citing an incident in which “songs praising the ‘Russian world’ were sung.”

The SBU said it searched 350 religious sites across Ukraine last month and more recently. It alleged the searches yielded pro-Russian materials, and accused a bishop of pro-Russia messaging. On December 7, it reported that a UOC priest from Lysychansk was sentenced to 12 years for tipping off Russian invaders to Ukrainian troop positions.

While the evidence shows some within the UOC remain pro-Moscow, the church also has publicly disagreed with Kirill’s position, Prodromou said.

Any enforcement actions need to be transparent and respect the religious liberty guaranteed in Ukraine’s constitution, said Prodromou, a former vice chair of the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom.

Even if there are pro-Russian elements in the church, “it still raises the question of what is to be done and whether this is a prudent step by the Ukrainian government,” she said, noting that in pluralistic Ukraine, a reduction of religious liberty for one group would be worrying for others.

“This is not only an Orthodox question. Other communities will be watching: Protestants, Greek Catholics, Jews, Muslims” as well as the OCU.

The UOC is being squeezed by all sides – from Russians claiming the church as their own to Ukrainians who see the OCU as Ukraine’s true church, said John Burgess, a Pittsburgh Theological Seminary professor and author of Holy Rus’: The Rebirth of Orthodoxy in the New Russia.

President Zelenskyy, too, is in a tight spot, Burgess said: “There’s such anti-Russian sentiment that (with) anything that can be tainted as somehow pro-Russian, he gets a lot of pressure to do something about it.”

But Prodromou said treating the entire UOC as disloyal “would be a mistake based on the empirical evidence and would also be imprudent because it would undermine the possibility of full reconciliation” between the two Orthodox churches.