The tsunami-wrecked Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant began releasing its first batch of treated radioactive water into the Pacific Ocean on August 24. It was a controversial step that alarmed neighboring countries.

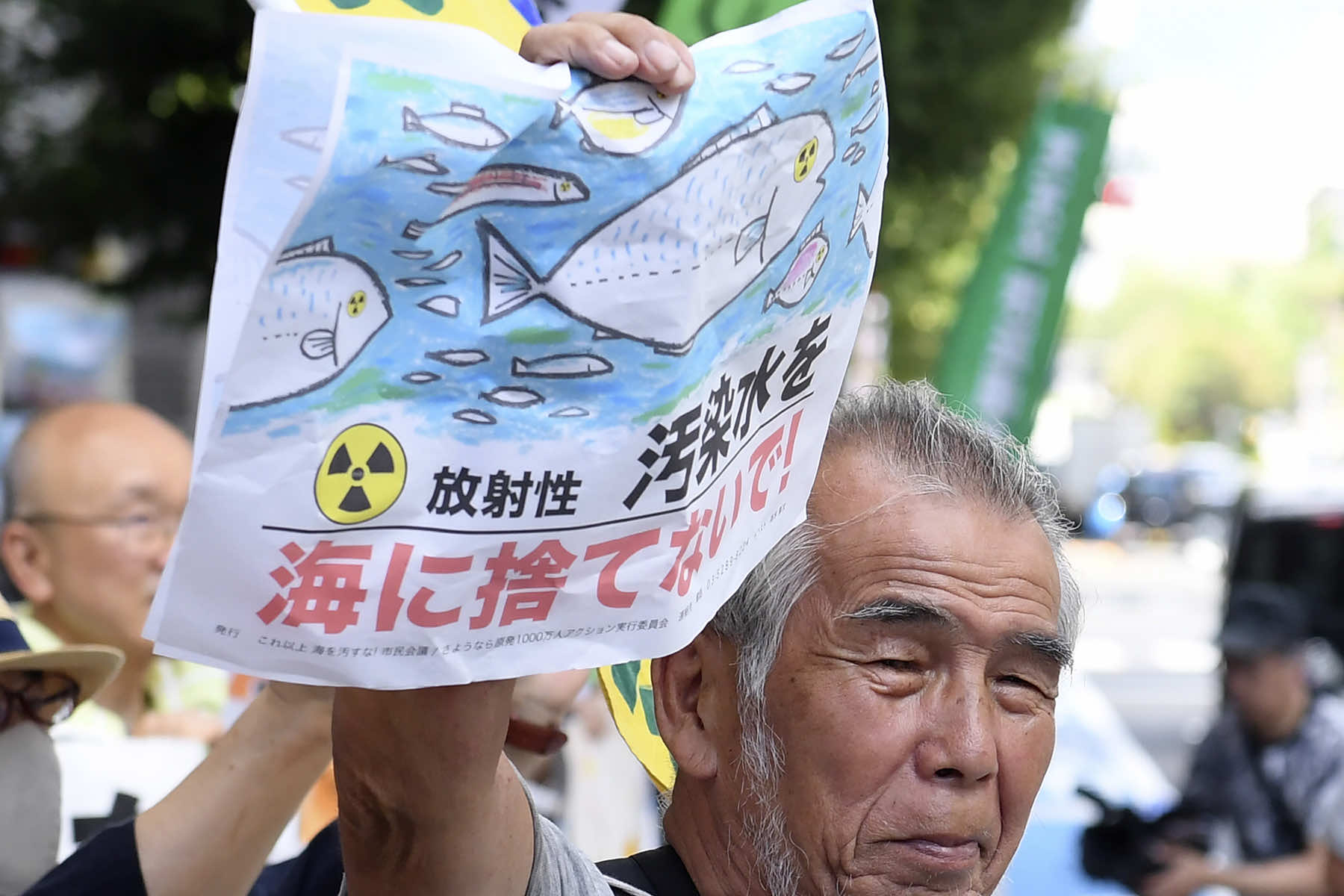

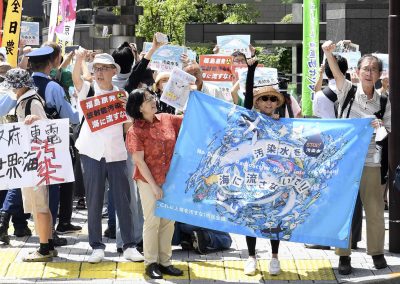

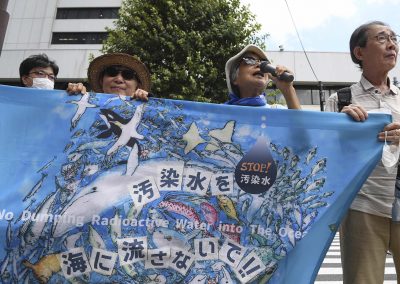

People inside and outside the country protested the wastewater release from Fukushima, with Japanese fishing groups fearing it would further damage the reputation of their seafood, and groups in China and South Korea raising concerns, making it a political and diplomatic issue.

Residents around Fukushima worry that the water discharge, 12 years after the nuclear disaster, could deal another setback to Fukushima’s image and hurt their businesses and livelihoods.

“Without a healthy ocean, I cannot make a living.” said Yukinaga Suzuki, a 70-year-old innkeeper at Usuiso beach in Iwaki about 30 miles south of the plant. And the government has yet to announce when the water release will begin.

While officials said the possible impact would be limited to rumors, it is not yet clear if it will be damaging to the local economy. Residents said they feel “shikataganai” — meaning helpless.

“If you ask me what I think about the water release, I’m against it. But there is nothing I can do to stop it as the government has one-sidedly crafted the plan and will release it anyway,” Suzuki said. “Releasing the water as people are swimming at sea is totally out of line, even if there is no harm.”

The beach, he said, was in the path of treated water traveling south on the Oyashio current from off the coast of Fukushima Daiichi. That was where the cold Oyashio current meets the warm, northbound Kuroshio, making it a rich fishing ground.

The government and the operator, Tokyo Electric Power Company Holdings, or TEPCO, have struggled to manage the massive amount of contaminated water accumulating since the 2011 nuclear disaster, and announced plans to release it to the ocean during the summer of 2023.

They said the plan is to treat the water, dilute it with more than a hundred times the seawater and then release it into the Pacific Ocean through an undersea tunnel. Doing so, they said, is safer than national and international standards require.

Suzuki was among those who are not fully convinced by the government’s awareness campaign that critics said only highlights safety. “We don’t know if it’s safe yet,” Suzuki said. “We just can’t tell until much later.”

The Usuiso area used to have more than a dozen family-run inns before the disaster. Now, Suzuki’s half-century old Suzukame, which he inherited from his parents 30 years ago, is the only one still in business after surviving the tsunami. He heads a safety committee for the area and operates its only beach house.

Suzuki said his inn guests do not mention the water issue if they cancel their reservations and he would only have to guess. “I serve fresh local fish to my guests, and the beach house is for visitors to rest and chill out. The ocean is the source of my livelihood.”

The March 11, 2011, earthquake and tsunami destroyed the Fukushima Daiichi plant’s cooling systems, causing three reactors to melt and contaminating their cooling water, which has since leaked continuously. The water is collected, filtered, and stored in some 1,000 tanks, which will reach their capacity in early 2024.

The government and TEPCO said the water must be removed to make room for the plant’s decommissioning, and to prevent accidental leaks from the tanks because much of the water is still contaminated and needs retreatment.

Katsumasa Okawa, who runs a seafood business in Iwaki, said those tanks containing contaminated water bother him more than the treated water release. He wants to have them removed as soon as possible, especially after seeing “immense” tanks occupying much of the plant complex during his visit few years ago.

An accidental leak would be “an ultimate strikeout … It will cause actual damage, not reputation,” Okawa said. “I think the treated water release is unavoidable.” It’s eerie, he adds, to have to live near the damaged plant for decades.

Fukushima’s badly hit fisheries community, tourism, and the economy are still recovering. The government has allocated $573 million to support still-feeble fisheries and seafood processing and combat potential reputation damage from the water release.

His wife evacuated to her parents’ home in Yokohama, near Tokyo with their four children, but Okawa stayed in Iwaki to work on reopening the store. In July, 2011, Okawa resumed sale of fresh fish —but none from Fukushima.

Local fishing was returning to normal operation in 2021 when the government announced the water release plan.

Fukushima’s local catch today is still about one-fifth of its pre-disaster levels due to a decline in the fishing population and smaller catch sizes.

Agricultural Minister Tetsuro Nomura acknowledged some fishery exports from Japan have been suspended at Chinese customs, and that Japan was urging Beijing to honor science.

“Our plan is scientific and safe, and it is most important to firmly convey that and gain understanding,” TEPCO official Tomohiko Mayuzumi told The Associated Press during its plant visit. Still, people have concerns and so a final decision on the timing of the release will be a “a political decision by the government,” he said.

Japan sought support from the International Atomic Energy Agency for transparency and credibility. IAEA’s final report, released this month and handed directly to Prime Minister Fumio Kishida, concluded that the method meets international standards and its environmental and health impacts would be negligible. IAEA Director General Rafael Grossi said radioactivity in the water would be almost undetectable and there is no cross-border impact.

Scientists generally agree that environmental impact from the treated water would be negligible, but some call for more attention on dozens of low-dose radionuclides that remain in the water, saying data on their long-term effect on the environment and marine life is insufficient.

Radioactivity of the treated water is so low that once it hits the ocean it will quickly disperse and become almost undetectable, which makes pre-release sampling of the water important for data analysis, said University of Tokyo environmental chemistry professor Katsumi Shozugawa.

He said the release can be safely carried out and trusted “only if TEPCO strictly follows the procedures as planned.” Diligent sampling of the water, transparency and broader cross-checks — not just limited to IAEA and two labs commissioned by TEPCO and the government — is key to gaining trust, Shozugawa said.

Japanese officials characterize the treated water as a tritium issue, but it also contains dozens of other radionuclides that leaked from the damaged fuel. Though they are filtered to legally releasable levels and their environmental impact deemed minimal, they still require close scrutiny, experts said.

TEPCO and government officials said tritium is the only radionuclide inseparable from water and is being diluted to contain only a fraction of the national discharge cap, while experts said heavy dilution is needed to also sufficiently lower concentration of other radionuclides.

“If you ask their impact on the environment, honestly, we can only say we don’t know,” Shozugawa, referring to dozens of radionuclides whose leakage is not anticipated at normal reactors, he said. “But it is true that the lower the concentration, the smaller the environmental impact,” and the plan is presumably safe, he said.

The treated water is a less challenging task at the plant compared to the deadly radioactive melted debris that remain in the reactors, or the continuous, tiny leaks of radioactivity to the outside.

Shozugawa, who has been regularly measuring radioactivity of groundwater samples, fish and plants near Fukushima Daiichi plant since the disaster, said his 12 years of sampling work shows small amounts of radioactivity from the Fukushima Daiichi has continuously leaked into groundwater and the port at the plant. He said its potential impact on the ecosystem also requires closer attention than the controlled release of the treated water.

TEPCO denied new leaks from the reactors and attributes high cesium in fish sometimes caught inside the port to sediment contamination from initial leaks and a rainwater drainage.

A local fisheries cooperative executive Takayuki Yanai told a recent online event that forcing the water release without public support only triggers reputational damage and hurts Fukushima fisheries. “We don’t need additional burden to our recovery.”

“Public understanding is lacking because of distrust to the government and TEPCO,” he said. “The sense of safety only comes from trust.”

In response to the wastewater release, Chinese customs authorities banned seafood from Japan, customs authorities announced Thursday. The ban affected all imports of “aquatic products” including seafood, according to the notice. Authorities said they will “dynamically adjust relevant regulatory measures as appropriate to prevent the risks of nuclear-contaminated water discharge to the health and food safety of our country.”

Seoul office worker Kim Mijeong said she intends to stop eating seafood because she deeply mistrusts the safety of Japan’s release of treated radioactive wastewater into the sea from its crippled nuclear power plant.

“We should absolutely cut back on our consumption of seafood. Actually, we can’t eat it,” Kim said. “I can’t accept the Japanese plan because it’s too unilateral and is proceeding without countermeasures.”

South Korean police detained 16 student activists on August 24 for allegedly trying to enter the Japanese Embassy illegally to protest the release. The activists entered the building housing the embassy, shouted slogans and unfolded banners but failed to enter embassy offices, according to police.

In South Korea, fierce domestic political wrangling has erupted over its own government’s endorsement of the Japanese plan. Liberal critics accused the conservative government led by President Yoon Suk Yeol of pushing to improve ties with Japan at the sacrifice of public health.

“The Yoon Suk Yeol government and the ruling People Power Party are accomplices in the dumping of the wastewater,” said Kwon Chil-seung, a spokesperson for the main opposition Democratic Party.

The governing party accused the opposition of inciting anti-Japan sentiment and public fears for political gain, undermining South Korea’s national interests and driving those in the domestic fisheries and seafood industries to the edge.

Yoon’s government and the Democratic Party have already fought bitterly over another Japan issue — Yoon’s contentious decision to take a major step toward easing historical grievances over forced Korean laborers during the Japanese colonial period.

The Democratic Party accused Yoon of making concessions to Japan without receiving steps in return. Yoon maintains that improved ties with Japan are necessary because of shared challenges like North Korea’s advancing nuclear arsenal and the intensifying U.S.-China rivalry.

Yoon administration officials have tried to ease public concerns by expanding radiation tests on seafood at major fish markets. Last month, some governing party lawmakers even drank seawater from fish tanks at a seafood market in Seoul to emphasize food safety.

But surveys of South Koreans show that more than 80% of respondents oppose the Japanese discharge plan and more than 60% said they won’t eat seafood after the water release begins.

“I totally oppose the Japanese plan. The radioactive wastewater is truly a bad thing,” said Lee Jae-kyung, a Seoul resident. “My feelings toward Japan have worsened because of the wastewater release.”

Fears about the wastewater are taking a heavy toll on some businesses in South Korea’s seafood industry. In a seafood market in the southeastern port city of Busan, fishmonger Kim Hae-cheol said his revenues have halved since a few months ago and worried that his business would suffer more after the start of the discharge.

“I haven’t had any customers today. In past years, I sold fish worth 400,000-500,000 won ($300-$380) by this time on a normal day,” Kim said in a midday phone interview Wednesday. “Others in this market have had few customers today as well.”

Kim said he trusts the safety reviews by the IAEA, Japanese, and South Korean officials, but that his business has been battered mainly because some opposition politicians and media outlets “make much ado.”

Hong Seong-been, a Seoul resident, said political strife over the release has left many with a lack of genuine information about whether the water is truly safe or not.

In Hong Kong, about a dozen residents took part in a march in a central business district to protest against Japan’s move.

After the protesters reached the building housing the Japanese Consulate, they tore up a big banner bearing Japan’s flag and the words “No trace of humanity. An enemy of the whole world.” Some held up placards calling for Kishida to step down.

The discharge plans have dealt a blow to Japanese restaurants which were already reeling from other problems, said Martin Chan, a director of the Hong Kong Federation of Restaurants and Related Trades. When Hong Kong follows China’s lead and bans all seafood from Japan, he will have to suspend operations at his Japanese restaurant, he said.

During lunch hour, some residents rushed to Japanese restaurants and supermarkets to have what they called their last “safe” sushi meals.

Housewife Vivian Li said she would stop eating aquatic products from Japan after finishing her sushi lunch. Li said she likes eating Japanese food but she had to make the decision due to health concerns.

“I want to act as a role model for my children, so they will stop eating these products even when they grow up,” she said.

But young professional Janet Yip said she would not cut her consumption of Japanese food because the release plans meet international standards.

In Taiwan, reactions to the release plan were muted. On a governmental level, Taipei is aligned with Tokyo on a score of issues and has not vocally opposed the discharge plan, which has been portrayed by Taiwanese media as conforming to international norms.

Taiwan’s Atomic Energy Council, a government agency, expressed concern in the past over the discharge. On Tuesday, it said it would closely monitor radiation levels in waters around Taiwan.

The Philippines, which receives coast guard vessels and other aid from Japan, also stressed that it was looking at the issue from a scientific perspective and recognized the IAEA’s expertise.

“As a coastal and archipelagic state, the Philippines attaches utmost priority to the protection and preservation of the marine environment,” the Department of Foreign Affairs said in a statement.