“And that is the core of our economic approach. To build. To build capacity, to build resilience, to build inclusiveness, at home and with partners abroad. The capacity to produce and innovate, and to deliver public goods like strong physical and digital infrastructure and clean energy at scale. The resilience to withstand natural disasters and geopolitical shocks. And the inclusiveness to ensure a strong, vibrant American middle class and greater opportunity for working people around the world. All of that is part of what we have called a foreign policy for the middle class.” – Jake Sullivan, National Security Advisor

Catie Edmondson and Carl Hulse in the New York Times yesterday noted that House speaker Kevin McCarthy (R-CA) cannot bring his conference together behind a budget plan. He wanted to pass a bill demanding major concessions from President Biden before the Republicans would agree to raise the debt ceiling, both to prove that he could get his colleagues behind a bill and to put pressure on the Biden administration to restore the old Republican idea that the only way to make the economy work is to slash taxes, business regulation, and government spending.

McCarthy was pleased to have passed his measure with not a single vote to spare, but it appears he got the vote because everyone knew it was dead on arrival at the Senate. According to Edmonson and Hulse, McCarthy got the bill through only by begging his colleagues to ignore the provisions of the measure because it would never become law. He urged them to focus on the symbolic victory of showing Biden they could unite behind cuts.

But at the Brookings Institution on April 28, National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan outlined a very different vision of the global economy and American economic leadership. First of all, just the fact this happened is significant: Sullivan is a national security advisor, and he was talking about economics. He outlined how Biden’s “core commitment,” “his daily direction” is “to integrate domestic policy and foreign policy.”

Sullivan argued for a new economic approach to the challenges of the twenty-first century. The Biden administration is trying to establish “a fairer, more durable global economic order, for the benefit of ourselves and for people everywhere.”

The U.S. faces economic challenges, he noted, many of which have been created by the economic ideology that has shaped U.S. policy for the past 40 years. The idea that markets would spread capital to where it was most needed to create an efficient and effective economy has been proven wrong, Sullivan said.

The U.S. cut taxes and slashed business regulations, privatized public projects, and pushed free trade on principle with the understanding that all growth was good growth and that if we lost infrastructure and manufacturing, we could make up those losses in finance, for example.

“When President Biden came into office more than two years ago, the country faced, from our perspective, four fundamental challenges. First, America’s industrial base had been hollowed out. The vision of public investment that had energized the American project in the postwar years — and indeed for much of our history — had faded. It had given way to a set of ideas that championed tax cutting and deregulation, privatization over public action, and trade liberalization as an end in itself. There was one assumption at the heart of all of this policy: that markets always allocate capital productively and efficiently — no matter what our competitors did, no matter how big our shared challenges grew, and no matter how many guardrails we took down. Now, no one — certainly not me — is discounting the power of markets. But in the name of oversimplified market efficiency, entire supply chains of strategic goods — along with the industries and jobs that made them — moved overseas. And the postulate that deep trade liberalization would help America export goods, not jobs and capacity, was a promise made but not kept.”

– Jake Sullivan, National Security Advisor

As countries lowered their economic barriers and became more closely integrated with each other, they would also become more open and peaceful.

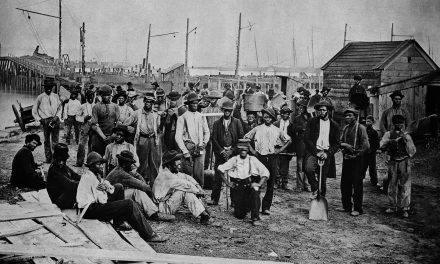

But that’s not how it played out. Privileging finance over fundamental economic growth was a mistake. The U.S. lost supply chains and entire industries as jobs moved overseas, while countries like China discarded markets in favor of artificially subsidizing their economies. Rather than ushering in world peace, the market-based system saw an aggressive China and Russia both expanding their international power. At the same time, climate change accelerated without countries making much effort to address it. And, most of all, the unequal growth of the older system has undermined democracy.

“Finally, we faced the challenge of inequality and its damage to democracy. Here, the prevailing assumption was that trade-enabled growth would be inclusive growth — that the gains of trade would end up getting broadly shared within nations. But the fact is that those gains failed to reach a lot of working people. The American middle class lost ground while the wealthy did better than ever. And American manufacturing communities were hollowed out while cutting-edge industries moved to metropolitan areas. Now, the drivers of economic inequality — as many of you know even better than I — are complex, and they include structural challenges like the digital revolution. But key among these drivers are decades of trickle-down economic policies — policies like regressive tax cuts, deep cuts to public investment, unchecked corporate concentration, and active measures to undermine the labor movement that initially built the American middle class. Efforts to take a different approach during the Obama Administration — including efforts to pass policies to address climate change, invest in infrastructure, expand the social safety net, and protect workers’ rights to organize — were stymied by Republican opposition. And frankly, our domestic economic policies also failed to fully account for the consequences of our international economic policies. For example, the so-called “China shock” that hit pockets of our domestic manufacturing industry especially hard — with large and long-lasting impacts — wasn’t adequately anticipated and wasn’t adequately addressed as it unfolded.”

– Jake Sullivan, National Security Advisor

Biden has attempted to counter the weaknesses of the previous economic system by focusing on building capacity to produce and innovate, resilience to withstand natural disasters and geopolitical shocks, and inclusiveness to rebuild the American middle class and greater opportunity for working people around the world. After two years, the results have been “remarkable.”

Large-scale investment in semiconductor and clean energy production has jumped 20-fold since 2019, with private money following government seed money to mean about $3.5 trillion in public and private investment will flow into the economy in the next decade. Building domestic capacity will bring supply chains home and create jobs.

But this vision is not about isolating the United States from other countries. Indeed, much of the speech reinforced U.S. support for the positions of the European Union.

Instead, the U.S. is encouraging our allies — including developing nations — to build similarly to increase our united economic strengths and to enable the world to address climate change together, a field that offers huge potential for economic growth.

The Indo-Pacific Economic Framework with 13 Indo-Pacific nations is designed to create international economic cooperation in that region, and the Americas Partnership for Economic Prosperity, which includes Barbados, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, the Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Mexico, Panama, Peru, and Uruguay, is designed to do the same here in the Americas. The United States-European Union Trade and Technology Council and our trilateral coordination with Japan and Korea are part of the same economic program.

With this economic approach, the U.S. does not seek to cut ties to China, but rather aims to cut the risks associated with supply chains based in China by investing in our own capacities, and to push for a level playing field for our workers and companies. The U.S. has “a very substantial trade and investment relationship” with China that set a new record last year, and the U.S. is looking not to create conflict but to “manage competition responsibly” and “work together on global challenges like climate, like macroeconomic stability, health security, and food security.”

“But,” he said, “China has to be willing to play its part.”

“Managing competition responsibly ultimately takes two willing parties. It requires a degree of strategic maturity to accept that we must maintain open lines of communication even as we take actions to compete. As Secretary Yellen said last week in her speech on this topic, we can defend our national security interests, have a healthy economic competition, and work together where possible, but China has to be willing to play its part.”

– Jake Sullivan, National Security Advisor

In today’s world, Sullivan said, trade policy is not just about the tariff deals that business leaders have criticized the administration for neglecting. It is about a larger economic strategy both at home and abroad to build economies that offer rising standards of living for working people.

The administration is now focusing on labor rights, climate change, and banking security in this larger picture. Through organizations like the Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment the administration hopes to mobilize hundreds of billions of dollars in financing in the next seven years to build infrastructure in low- and middle-income countries and to relieve debt there.

“The world needs an international economic system that works for our wage-earners, works for our industries, works for our climate, works for our national security, and works for the world’s poorest and most vulnerable countries,” Sullivan said. That means replacing the idea of free markets alone with “targeted and necessary investments in places that private markets are ill-suited to address on their own.” Rather than simply adjusting tariff rates, it means international cooperation.

“It means returning to the core belief we first championed 80 years ago: that America should be at the heart of a vibrant, international financial system that enables partners around the world to reduce poverty and enhance shared prosperity. And that a functioning social safety net for the world’s most vulnerable countries is essential to our own core interests.”

– Jake Sullivan, National Security Advisor

This strategy, he said, “is the surest path to restoring the middle class, to producing a just and effective clean-energy transition, to securing critical supply chains, and, through all of this, to repairing faith in democracy itself.” He called for bipartisan support for this approach to the global economy.

Sullivan noted that the phrase “a rising tide lifts all boats” came from President John F. Kennedy, not from later supply-side ideologues who used it to defend their tax cuts and business deregulation. “President Kennedy wasn’t saying what’s good for the wealthy is good for the working class,” Sullivan said, “He was saying we’re all in this together.”

Sullivan quoted Kennedy further: “If one section of the country is standing still, then sooner or later a dropping tide drops all the boats. That’s true for our country. That’s true for our world. [And] economically, over time, we’re going to rise — or fall — together. And that goes for the strength of our democracies as well as for the strength of our economies.”

Hеаthеr Cоx Rіchаrdsоn and MI Staff

Andrew Harnik (AP), Evan Vucci (AP), and J. Scott Applewhite (AP)

Letters from an Аmerican is a daily email newsletter written by Heather Cox Richardson, about the history behind today’s politics