The debt ceiling is not about future spending; future spending is debated when Congress takes up the budget. The debt ceiling is a curious holdover from the past, when Congress actually wanted to enable the government to be flexible in its borrowing rather than holding the financial reins too tightly.

In the era of World War I, when the country needed to raise a lot of money fast, Congress stopped passing specific revenue measures and instead set a cap on how much money the government could borrow through all of the different instruments it used.

Beginning in the 1980s, though, Republicans began to use the debt ceiling as a political cudgel because if it is not raised when Congress spends more than it has the ability to repay, the country will default on its debts. Republicans focused on cutting taxes, initially promising that tax cuts would not require any cuts to services because they would nurture the economy so effectively that tax revenues would increase despite the cuts.

Immediately, though, both deficits—the difference between what the government spends and what it takes in—and the debt, which is the total sum that the government owes, ballooned.

That skyrocketing debt means that Congress repeatedly has to increase the amount that the Treasury borrows to pay the country’s bills. That is, it must lift the debt ceiling. Congress has raised the debt ceiling more than 100 times since it first went into effect, including 18 times under Ronald Reagan as well as 3 times under former president Donald Trump.

The United States has never defaulted on its debt. When Republicans threatened to push a debt crisis in late 2021, Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen warned that a default “could trigger a spike in interest rates, a steep drop in stock prices, and other financial turmoil. Our current economic recovery would reverse into recession, with billions of dollars of growth and millions of jobs lost.”

It would jeopardize the status of the U.S. dollar as the international reserve currency. Financial services firm Moody’s Analytics warned that a default would cost up to 6 million jobs, create an unemployment rate of nearly 9%, and wipe out $15 trillion in household wealth.

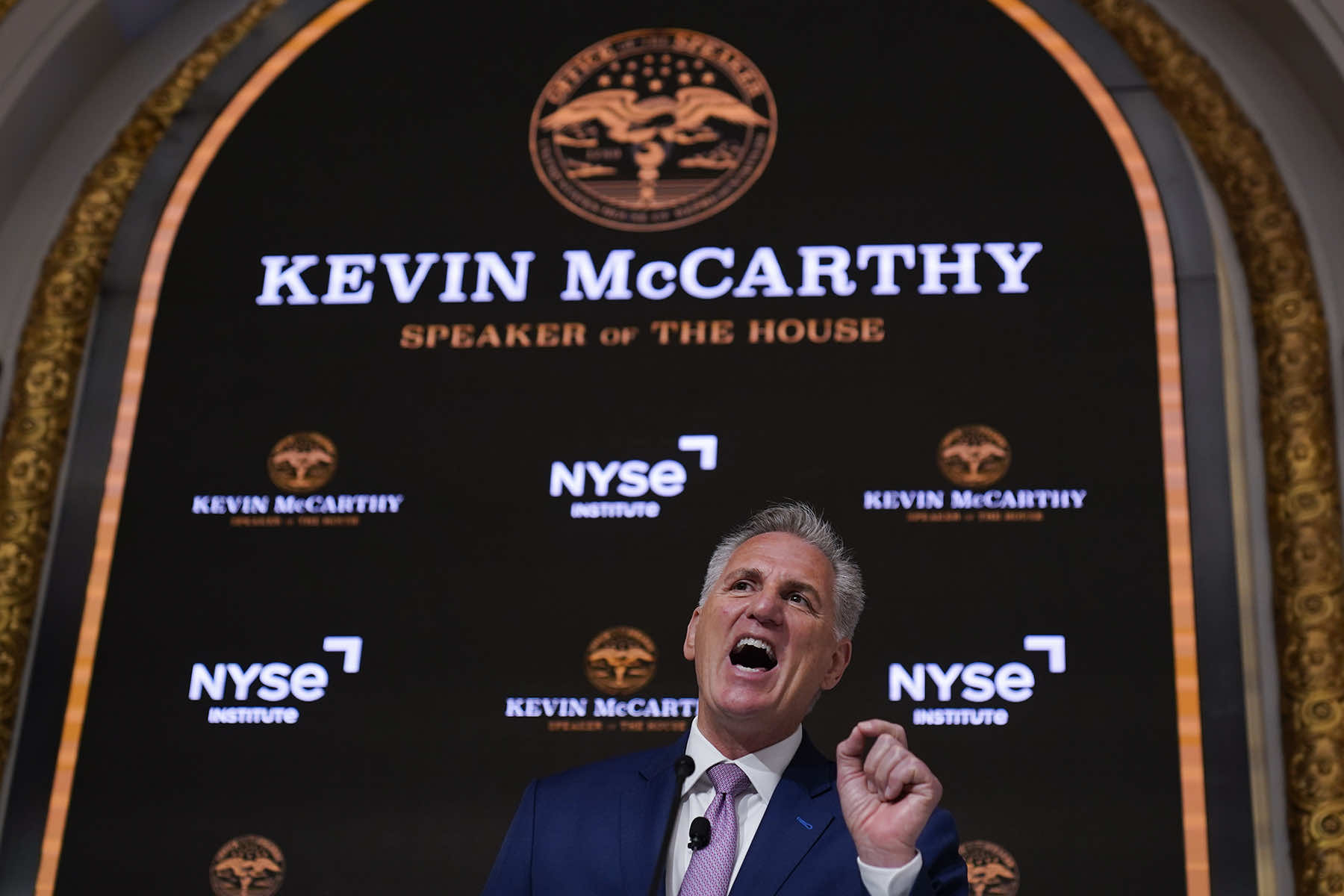

Now House Republicans under speaker Kevin McCarthy are insisting they will force the country into default unless Biden and the Democrats abandon their legislative program and do what the Republicans want. And what they want is to enact a drastic version of the Republican platform of the past 40 years. On April 19, McCarthy introduced a 320-page measure that would address the deficit and growing debt by drastic cuts to government programs across the board.

It is largely a wish list of right-wing demands such as a repeal of key measures of the Inflation Reduction Act, including those addressing climate change and funding the Internal Revenue Service; additional requirements to qualify for benefit programs; and getting rid of the program to forgive certain student debt. It would lift the debt ceiling only for a year, meaning the government would be right back to negotiating over it almost immediately.

There are two things at work behind this demand. The first is that the Republicans are in such extraordinary disarray that they are unable to put forward a budget—which is part of the normal process of funding the government—because they are unable to agree on one that can get enough votes to pass the House.

Different factions in the party want cuts that, even if they could get through the House, would never pass the Senate, and the farthest-right group of lawmakers have indicated they won’t agree to anything. With this grab-bag measure, McCarthy is trying to cover all his bases, but already some of his conference is torn that it goes too far…or not far enough.

That inability to get their way through normal political channels illustrates the larger story behind the Republicans’ position: they want to destroy the government as it has existed since 1933, but since that government is actually quite popular, they cannot get the cuts they want by going through normal legislative procedures. Instead, they are trying to get their demands by holding the rest of us hostage.

It is notable that while the Republicans are willing to slash education, food safety, and so on, they want to preserve the Trump tax cuts for the wealthy and corporations that cost the Treasury $2 trillion. Their stated concern for financial responsibility is also undermined by the reality that repealing the funding for the woefully understaffed IRS is expected to cost the Treasury $124 billion as wealthy tax cheats continue to avoid enforcement.

McCarthy is doubling down on his debt ceiling demands in part because the Republican base is wedded to Trump, which means the Republican Party is now wedded to Trump, and Trump insists that Republicans must use the debt ceiling to get what they want.

Early hopes that they could run a Trump-like candidate without the Trump baggage—someone like Florida governor Ron DeSantis—are starting to fade. Matt Dixon of NBC News reported that although the DeSantis team asked him to hold off on an endorsement, the co-chair of the Florida congressional delegation, Vern Buchanan, has endorsed Trump.

Buchanan said that Trump will “get our economy back on track,” including lowering taxes and “promoting America-first trade deals.” A former chair of the Florida Chamber of Commerce, Buchanan is one of the wealthiest members of Congress.

He clearly continues to believe that the key to boosting the economy is more tax cuts and is willing to accept all the other pieces of another Trump presidency—Trump has recently called for vengeance against his enemies, replacing civil servants with his own loyalists, and attacking Mexico—so long as the United States government embraces the supply side economics the Republicans have advanced since 1981.

President Joe Biden contrasted his own vision for the United States to that of the Republicans when he spoke at the International Union of Operating Engineers Local 77 in Accokeek, Maryland, in a corrugated-steel garage. His own vision, he reiterated, calls for building the economy from the middle out and the bottom up, not from the top down.

He outlined how the Democrats’ many investments in infrastructure and manufacturing have benefitted working- and middle-class Americans, while Republicans have sought to cut those investments and cut taxes for the wealthy. Biden wants to address the deficit by rolling back Republican tax cuts on the wealthy and on corporations, saying it’s high time they paid their fair share.

McCarthy is trying to spin the crisis in his own conference as Biden “playing partisan games,” and Republicans say they hope that passing their measure will force Biden to negotiate over the debt ceiling. But Biden has steadfastly refused to negotiate over the credit of the government, although says he is quite happy to negotiate over the budget, which is part of the normal legislative process.

House minority leader Hakeem Jeffries backed up Biden, saying: “The United States of America must always pay bills already incurred without gamesmanship, brinksmanship, or partisanship. House Democrats will oppose any effort to hold the economy hostage as part of any scheme by Extreme MAGA Republicans to jam its right-wing agenda down the throats of the American people.”

Their refusal to negotiate over the nation’s finances puts them in good company. We have seen a scenario just like this one before. In 1879, when the positions of the parties were reversed, Democratic former Confederates won control of Congress for the first time since the Civil War.

Once in power, they banded together, demanded the leadership of key committees—which the exceedingly weak speaker gave them—and set out to make the Republican president, Rutherford B. Hayes, stop protecting Black voters by refusing to fund the government until he caved.

Southern Democrats told newspapers they had blundered when they fought on the battlefields: far better to control the country from within Congress. Extremist newspapers threatened violence as they called for Congress members to “drive or starve Mr. Hayes into signing a bill that sweeps these obnoxious laws out of existence.”

House minority leader James Garfield (R-OH) noted: “They will let the government perish for want of supplies.” “If this is not revolution, which if persisted in will destroy the government, [then] I am wholly wrong in my conception of both the word and the thing.” A Civil War veteran who had seen battle at Shiloh and Chickamauga, Garfield understood revolution.

Hayes stood firm, recognizing that allowing a radical minority of the opposition party to dictate to the elected government by holding it hostage would undermine the system set up in the Constitution. The parties fought it out for months until, in the end, the American people turned against the Democrats, who backed down.

In the next presidential election, which had been supposed to be a romp for the Democrats, voters put Garfield, the Republican who had stood against the former Confederates, into the White House.

Seth Wenig (AP)

Letters from an Аmerican is a daily email newsletter written by Heather Cox Richardson, about the history behind today’s politics