Because the Marcus Center for the Performing Arts space is leased from the County of Milwaukee, the Cultural Landscape Foundation believes there should be public input from design professionals and a vote by citizens about how the site is altered before plans move forward with its demolition.

The Marcus Center for the Performing Arts in downtown Milwaukee, Wisconsin, is a masterfully designed campus whose building, by architect Harry Weese, and landscape, by Dan Kiley, exist in harmonious equilibrium. Despite being an exemplary collaboration between these two masters of their craft, the cultural venue recently unveiled plans to obliterate Kiley’s grid of horse chestnut trees for the sake of a more flexible outdoor space.

In 1965 landscape architect Dan Kiley and Chicago architect Harry Weese were working together on the design of an arts complex at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. The two men had just completed their work on the IBM Headquarters in Milwaukee. During this period of fruitful collaboration, Weese was also commissioned to design the Milwaukee Performing Arts Center (now the Marcus Center for the Performing Arts) at 929 East Water Street in Milwaukee, and he asked Kiley to join him on the project.

This would be a continuation of a long-term working relationship that included the Rochester (New York) Institute of Technology, Reed College in Portland, Oregon, the First Baptist Church in Columbus, Indiana (now a National Historic Landmark), Grant Park in Chicago, Illinois, and Forest Park Community College in St. Louis, Missouri.

Construction on Milwaukee’s new Performing Arts Center began in June 1966, with Kiley’s design for the surrounding grounds well in hand by then. Kiley was known for the keen architectonic sense he brought to many projects, which, in this case, was matched by the special interest that Weese took in the landscape. The dialogue between the two practitioners, each at the top of his respective profession, is evident in the seamless dialogue between the landscape and the architecture. The facades of Weese’s building were articulated in bold but simple planes of travertine. Kiley’s landscape was equally bold in form and simple in materiality.

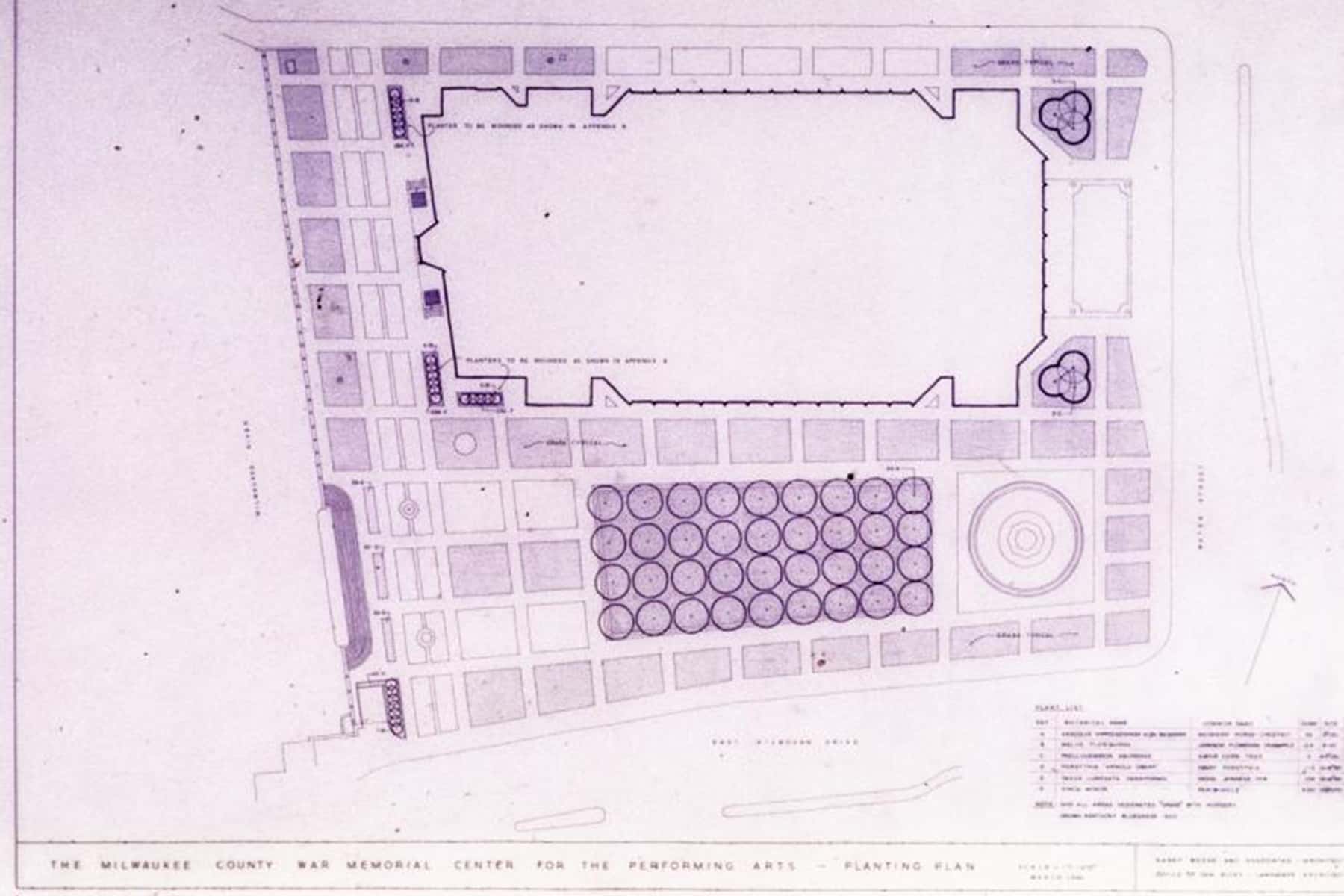

His plan for the center’s grounds, located beside the Milwaukee River, called for a grid of grass rectangles set within the pavement surrounding a central, trapezoidal plaza. That central space, sunken three steps below the adjacent walkways (recalling the better-known South Garden at the Chicago Art Institute, designed and constructed from 1962 to 1967), mimicked the conversation pit of the famous Miller House and Garden, which Kiley had completed with architect Eero Saarinen in Columbus, Indiana, in 1957 (and which became a National Historic Landmark in 2000).

The interior of the plaza was covered in crushed stone and planted with 36 horse chestnut trees laid out in a 4 x 9 grid. The meticulously placed rows of trees are slightly more than eighteen feet apart on the eastern end of the plaza, increasing to just over 21 feet apart on the western end. The careful spacing created the illusion of a perfect rectangle, masterfully disguising the slightly trapezoidal shape of the plaza.

The grid of horse chestnuts also speaks directly to Kiley’s time in Europe, specifically in Paris, France, where, as has been well documented, he was influenced by the garden of the Tuileries (also planted with horse chestnut trees), the imperial palace on the right bank of the Seine. What Kiley recognized there—and translated to great advantage in Milwaukee—was “a language of form used to conduct the movement of daily life, a language with which to vocalize the dynamic hand of human order on the land—a way to reveal nature’s power and create spaces with structural integrity,” as he put it. He would also recall that his experience at the Tuileries opened his eyes to “the spatial and compositional power of the simplest of elements—this was no less than living architecture.” The Performing Arts Center’s plaza in Milwaukee is a virtual illustration of these thoughts and words.

Complementing the simple bosque of trees are twelve-foot-high pylon lights designed especially for the project by Weese. The concrete benches that fill the plaza today, however, are not original to the design. Keeping true to the idea that urban life could and should happen spontaneously and unprogrammed, even within a highly ordered landscape, Kiley specified that moveable tables and chairs be set among the trees, allowing the plaza to function as an extension of the Performing Arts Center’s interior spaces. The use of moveable tables and chairs did not enter the mainstream of landscape design until 1967, with the opening of Paley Park in New York City; the use of these furnishings at the Marcus Center was thus a pioneering effort to create a flexible outdoor space.

On December 7, 2018, the Marcus Center for the Performing Arts unveiled its vision for a reimagined campus, which called for the Dan Kiley landscape to be obliterated. The Marcus Center reportedly seeks to create a more open and flexible campus in order to help generate revenue and host more events.

To achieve this, the current design proposes to replace the grove of horse chestnut trees with a large lawn intended to be used as a viewing area for outdoor performances. Movable seating would be included on the lawn—an ironic nod to Kiley’s original design, which included just that within the planted plaza, whose shade-giving trees would surely be missed, especially as temperatures, already on the rise, are only projected to increase in the coming decades.

The center’s press release stated that the grove of horse chestnuts now sees little use, calling it a “black forest” that exudes “really dark shade.” The statement also noted that Milwaukee County has committed $10 million to the project, which calls for changes and additions to Weese’s building. The project is expected to take from three to five years to complete and is slated to begin in Spring 2019.

Kiley’s work on the Performing Arts Center is significant for many reasons. It is a masterful demonstration of the skill and vision that brought him international acclaim as a pioneer of Modernism in designed landscapes and as a recipient of the National Medal of Arts (1997), a rare achievement for a landscape architect. Moreover, Kiley’s work on the nearby Cudahy Gardens at the Milwaukee Art Museum, opened to the public in 1998, was his last fully realized public commission.

To have, within blocks of each other, two public projects that bookend the civic career of one of the most important postwar landscape architects is of great cultural significance for the City of Milwaukee — a distinction that once forfeited can never be regained, and one that should be carefully weighed against the center’s plans, especially given its stated mission to provide “the best of cultural and community programming.”

Jennifer Current

Joe Karr

Originally published as Demolition of Dan Kiley Landscape in Milwaukee Announced